This Article From Issue

November-December 2004

Volume 92, Number 6

DOI: 10.1511/2004.50.0

Typologies. Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher. Edited and with an introduction by Armin Zweite. 35 pages and 130 plates. The MIT Press, 2004. $75.

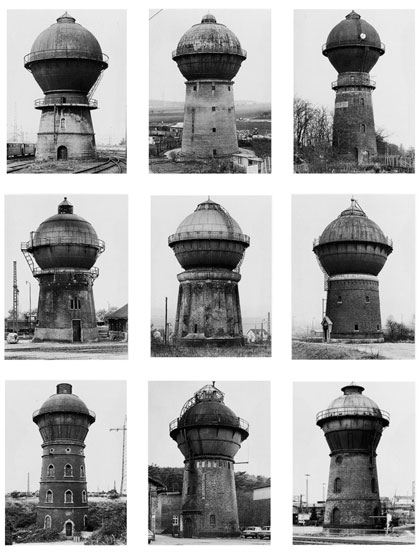

Typologies is like a family photo album—a big book whose square pages hold many small images, arranged thematically. But here there are no vacation snapshots of the Grand Canyon at sunset, no "I was there" photographs taken atop the Eiffel Tower or the Great Wall of China. The subjects of these images are industrial artifacts: water towers, gas tanks, mine hoists, lime kilns, grain elevators, coal bunkers, blast furnaces. The photos are arrayed 9 or 15 to the page, and they have a certain sameness to them. No two objects are quite identical, but the family resemblances are striking.

Bernd and Hilla Becher have been making these images in collaboration for 45 years, starting in the mining and metalworking districts of Germany and later roaming to other parts of Europe and occasionally the United States. The genre of their work is art photography; the prints are exhibited in galleries and discussed in art journals. But the photos also serve to document elements of the landscape that often go unnoticed and unappreciated. Although a few kinds of man-made structures—lighthouses, old barns, covered bridges—are considered picturesque and therefore come to adorn calendars and travel-agency posters, most industrial artifacts are ignored or deliberately concealed. Other photographers turn their backs on the power line or the smokestack; the Bechers stare at these objects steadily and straight on. In the introduction to this volume Armin Zweite writes: "It is Bernd and Hilla Becher's outstanding achievement, and it should not be underestimated, to have directed our attention to something that we previously did not notice or certainly did not perceive in the way it appears in the Bechers' photographs."

From Typologies.

Of course the Bechers were not the first to poke a lens into the industrial landscape. Lewis Hine photographed steel mills and coal mines, and Margaret Bourke-White did portraits of dams and bridges. But the Bechers approach these technological landscapes with a different aim and a different aesthetic. Where others seek out dramatic lighting, angular perspective and scenes of action, the Bechers choose to make their photographs on overcast days with flat, shadowless, directionless light, and they place the camera in the most neutral position possible, so that the structure is centered and scaled to fill the frame. They adjust the lens board and bellows of their view camera to preserve the rectilinearity of the image: All of those upright tanks and towers have their sides exactly parallel, never receding in perspective. Nothing "happens" in these pictures; in particular, there are no human figures visible. Here is how Zweite describes this depopulated landscape (and note that these are to be taken as words of praise!):

What the Bechers' photographs show us is a world in differentiated gray tones, a lifeless, abandoned, seemingly almost artificial terrain, bereft of movement and yet often signaling the flow of energy, sometimes chilly, often inaccessible, for the lay viewer in many ways strange and in part with a distanced feel to it.

Several earlier collections of the Bechers's photos presented them as individual images, one to a page, in the usual art-book manner. The format of Typologies, with its catalogue-like arrays of many small images, better suits the subject matter. Instead of calling attention to the peculiarities of a single object, the columns and rows invite a comparative examination, the way one might peruse a collection of butterflies pinned to a wax tray.

Two disappointments: Unlike some of the earlier books, this one offers no commentary explaining the function of the objects in the photographs. Also, the artifacts chosen for display are all of a certain age; the Bechers seem to have little interest in structures built since about 1950. This last point may have a ready explanation. Bernd Becher was born in the industrial Siegerland region of Germany, and he reports that one motive for his photography is "looking for places that resemble those where I grew up." In other words, Typologies is even more like the family photo album than one might first guess: However austere and static these images may seem, there is nostalgia and sentimentality in them.—Brian Hayes

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.