This Article From Issue

September-October 2012

Volume 100, Number 5

Page 422

DOI: 10.1511/2012.98.422

AMERICAN GEORGICS: Writings on Farming, Culture, and the Land. Edwin C. Hagenstein, Sara M. Gregg, and Brian Donahue, editors. xx + 406 pp. Yale University Press, 2011. $35.

Forty-eight years ago in his groundbreaking book, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, historian Leo Marx cited Thomas Jefferson to illuminate the tension between farming and industry that has characterized land use in the United States for more than two centuries. Jefferson’s wish, evident in the frequently quoted “Query XIX” from his 1787 Notes on the State of Virginia, was that the United States remain a nation of citizen farmers. Raw materials, he wrote, should be sent overseas to Europe for manufacture. As Marx noted, Jefferson believed otherwise 30 years later. In a letter to Benjamin Austin, a writer for Boston’s Independent Chronicle, Jefferson acknowledged that in light of America’s uneasy relationship with Britain and France as a result of the Reign of Terror and the War of 1812, “manufactures are now as necessary to our independence as to our comfort.” American Georgics , a fine anthology and the most recent addition to the Agrarian Studies Series from Yale University Press, reveals that in the interval since Jefferson concluded that U.S. citizens needed to make industry integral to the nation’s fabric these two antithetical impulses—agrarian and industrial—have remained firmly in place.

The editors, Edwin C. Hagenstein, Sara M. Gregg and Brian Donahue, have divided the volume into seven chronological chapters, each preceded by an introductory essay. The first, “Shaping the Agrarian Republic, 1780–1825,” contains early discussion about the role of the farmer and farming in American culture. It includes important excerpts from J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur’s Letters from an American Farmer, along with relevant commentary from James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, among others. Is farming an ennobling and civilizing endeavor, as de Crèvecoeur, Madison and Jefferson claimed? Does it lead to a more virtuous life than industry? Should farms remain manageably small or, as Hamilton advised, take advantage of new machinery to increase size and enhance production? The chapter also introduces agrarianism as manifested in the South and considers the ways in which slavery makes complicated both practical ideas and philosophical ideals about husbandry.

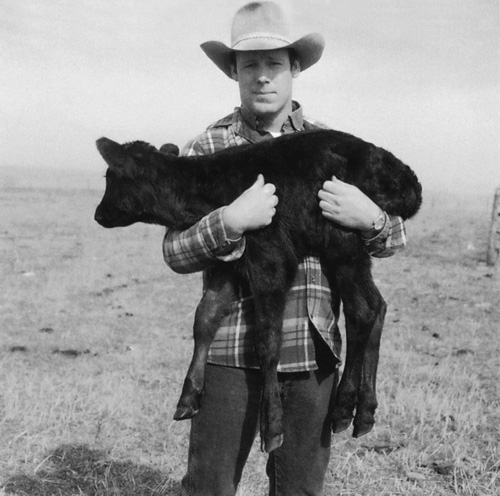

From American Georgics .

Subsequent chapters show how these early concerns and debates have evolved. We learn of the adaptation of farming techniques in America in light of the Industrial Revolution, the passage of the Homestead Act, the increased specialization of farms and farming jobs, and the closing of the frontier. In addition, we come to understand the effect of the new railway system that engendered more efficient transport of crops even as it left farmers completely dependent on the vagaries of its pricing, often exorbitant due to lack of competition. The cultural foundations for agrarianism are represented by institutions such as the People’s Party and the Southern Farmers’ Alliance, active in the late 1800s, and Friends of the Land, begun in the 1940s and championed by Aldo Leopold. Two literary movements that focused on land use also contributed to the agrarian ideal: American Romanticism in the mid-1850s and, in the next century, the Southern Agrarians, a group of writers best known for their contributions to the essay collection and manifesto I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition, published in 1930. The final chapter brings us to the present and includes selections from such luminaries as Aldo Leopold, Wes Jackson—who also wrote the foreword to this volume—and Wendell Berry.

From American Georgics .

The editors have likewise reprinted some excellent, lesser-known excerpts, such as George Perkins Marsh’s 1847 “Address to the Agricultural Society of Rutland County,” Wilson Flagg’s 1859 “Agricultural Progress” and Liberty Hyde Bailey’s 1915 “The Holy Earth”—a call for a moral relation to the land made well before Leopold proffered his “land ethic” in A Sand County Almanac, published in 1949. American Georgics makes clear that the issues surrounding farming have changed more in degree than in kind. One wonders, then, whether alternative attitudes toward the land ever will be realized in the United States. The editors observe in the book’s conclusion that “A renewed appreciation for connection with soil and community has captured the interest of a growing and influential segment of American food culture.” This “new wave of agrarianism” is identified as comprising mostly those who can better afford the higher prices of farmer’s markets and organic produce. Whether these neoagrarians and the organizations they have founded will be willing to make the long-term sacrifices necessary to bring wholesome, locally grown food and sustainable farming practices to those who exist at the economic margins of society remains to be seen.

American Georgics clearly is directed towards this more affluent audience that is supportive of the agrarian movement, which in its present incarnation advocates for smaller farms that are intimately connected to the welfare of the land and the immediate community. The book includes only a few opposing arguments, such as an excerpt from Edwin G. Nourse, who argued in 1919 that a better standard of living for all Americans could only be achieved once “a considerable fraction of our population” was “freed from the soil” to pursue other callings, and one from Earl L. Butz, who in 1960 believed the nation’s highest priority should be an increased standard of living, based on efficient food production and marketing, for all citizens regardless of economic standing. These interruptions provide welcome perspective in a book that comes uncomfortably close to promulgating a single point of view.

In a similar vein, the editors’ commentary is generally excellent, profoundly enlarging the history of agrarianism and the particulars of each selection. But in several places, I felt that the discussion could better encompass divergent points of view. For example, the book presents American Romanticism as antithetical to agrarianism because, as the editors write, “In turning from the ugliness of industrial civilization toward an idealized wild nature, Romantics left the pastoral ‘middle landscape’ in an uncertain position.” This perspective overlooks the importance of these mid-19th-century writers, whose sense of nature’s sublimity helped alert the public to the importance of preservation and conservation. Although preservation is, as the editors indicate, not usually in the best interests of the agrarian, the Romantics’ regard for an unaltered landscape was prescient. Sixty years later Bailey observed, “We have been obsessed of the passion to cover everything at once, to skin the earth . . . even when there was no necessity for so doing.” Similarly, Leopold advocated for “restrained use” that would include an “interspersion of land uses, a certain pepper-and-salt pattern in the warp and woof of the land-use fabric,” where the “fields and pastures . . . are a mixture of wild and tame attributes, all built on a foundation of good health.”

The editors also make light of Thoreau, who, they note, “put in only half a day with his hoe” so that he could have time to walk, read and write. This stance is odd; elsewhere in the book, moderation is repeatedly called for and is celebrated as integral to proper land use and the health of communal culture. That the Romantics sought spiritual and aesthetic good health makes their program no less important than the agrarian emphasis on the more literal good health of the flesh. It deserves commentary as admiring as the book affords the Southern Agrarians, who were similarly idealistic in their celebration of Southern farm life in the early part of the 20th century.

I was surprised as well to find only brief mention of Leo Marx, despite the fact that the third chapter of this book, “The Machine in the Garden: The Rise of American Romanticism,” takes its title from his exceptional work of cultural and literary criticism. “The machine in the garden” is a reference to the sound of the steam locomotive Thoreau hears at Walden Pond—a sound he is intrigued by yet eschews. This conceit, established by Marx, is emblematic of the conflict between agrarianism and industrial progress that pervades the book . The editors give Marx less credit than he deserves because they confuse the pastoral—a literary idea with its source in the first-century-B.C.E. Roman poet Virgil’s Eclogues —with agrarianism, which, like Virgil’s Georgics, from which this volume takes its title, has a firm grounding in the practical work of farming. Marx makes this distinction and brilliantly reveals why Jefferson’s ideal of the citizen farmer, mentioned at the beginning of this essay and inspired by the utopian values of Virgil’s Arcadia, was untenable. In addition, the book should have included endnotes. I was intrigued by a comment made by Abraham Lincoln and another by T. S. Eliot, to name just two; both quotations were included in the editors’ introductions to the chapters, but no documentation of primary sources was provided.

Finally, the editors should have paid more attention to the expertise of Native cultures. The book offers little recognition that the agrarian ideals of crop rotation and crop diversity coincide with Native ideas about land use, or that most of the Native population of the United States was relocated to reservation land that provided scarce opportunity for successful farming. For example, the authors would have done well to include an excerpt from “Creations,” one of many fine essays by Linda Hogan. She writes:

Without deep reflection, we have taken on the story of endings, assumed the story of extinction. . . . We need new stories, new terms and conditions that are relevant to a love of land, a new narrative that would imagine another way. . . . Indian people must not be the only ones who remember agreement with the land, the sacred pact to honor and care for the life that, in turn, provides for us.

Hogan’s words are well in line with the aspirations of contemporary agrarians. Since the editors’ intention is to reinforce and expand the audience for responsible land use, it is imperative that they spread their net as widely as they can and forge alliances with those Native cultures that have long been dismissed as well as with others who support land conservation.

These criticisms in no way invalidate the importance of this volume. American Georgics is a gem, chock-full of essays and excerpts that are invaluable to an understanding of farming and conservation, and driven by a vision of what landscape and husbandry might become in the United States if we as a nation could think more holistically about what would most benefit us. It is also a wonderful resource for teaching and a step in the direction espoused by Leopold, Jackson and others in this anthology: that through dissemination of knowledge and better education, we might be able to redirect our culture toward a fuller appreciation of our fertile, fragile planet.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.