This Article From Issue

January-February 2009

Volume 97, Number 1

Page 68

DOI: 10.1511/2009.76.68

THE TRAGIC SENSE OF LIFE: Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle over Evolutionary Thought. Robert J. Richards. xx + 551 pp. University of Chicago Press, 2008. $39.

Decades of intense study of Darwin’s life, intellectual development, and social and political context have generated new kinds of questions about a number of matters: the interpersonal networks supporting him; the lives of the admirers and critics of his ideas; the dissemination and reading of evolutionary works; the sources of evolutionism in earlier French, German and British thought; and Darwin’s reception by various national and social groups. In the spirit of these expanding horizons of Darwin scholarship, The Tragic Sense of Life, by Robert J. Richards, provides not only a biography of the controversial German evolutionist Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), but also an important piece of the emerging picture of the Darwinian Revolution in its international and intergenerational dimensions.

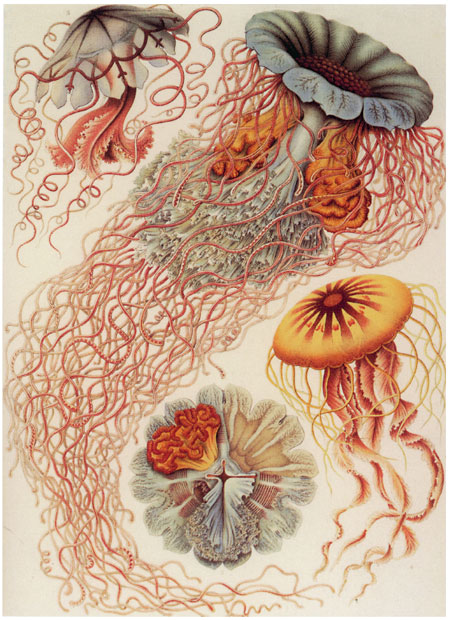

From The Tragic Sense of Life.

Darwin biographers Adrian Desmond and James Moore once remarked that the many previous books on their subject had been “curiously bloodless affairs.” Richards could almost say the same now about the Haeckel literature—were it not for the frequent attacks that have battered and bloodied the reputation of Haeckel, who has been accused of everything from scientific fraud and incompetence to racism, anti-Semitism and proto-Nazism.

Richards therefore has a threefold task: He must respond to the Haeckel-bashing and clean house. He must develop a better approach to, and a 19th-century context for, Haeckel’s work. And he must put the blood back into Haeckel’s veins and show us how it once rushed with emotion over loves, losses and infatuations, boiled with anger at religion and superstition, and nourished the brain of a scientific and artistic genius, whose ideas “pulsed to the rhythms orchestrated by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Alexander von Humboldt, and Matthias Jakob Schleiden.” The three tasks are intertwined throughout the book, but I will try to discuss them separately.

Richards’s context for Haeckel is an intellectual one that stretches from the Age of Goethe and the German Romantics, through the generation of Haeckel’s teachers (all scientific luminaries of the 1850s, such as Johannes Müller, Rudolf Virchow and Albert von Kölliker), to Charles Darwin. Haeckel builds on this intellectual foundation, also taking inspiration from a younger generation of intellectual allies, including the morphologist Carl Gegenbaur and the pioneering historical linguist August Schleicher. Haeckel defends the resulting system of thought against a variety of opponents, ranging from embryologist Wilhelm His to Jesuit myrmecologist Erich Wasmann. But this is not intended as a story of the march of ideas or intellectual influences in the abstract. Richards stresses that ideas can only effect historical change when living, feeling people are motivated to embrace them and put them to use. That is why the biographical element is crucial, and why a bloodless Haeckel will not do.

As the title The Tragic Sense of Life suggests, however, Richards’s Haeckel is often more melancholy than sanguine. This is mainly because of the death of his first wife Anna in 1864, just as his career as an evolutionary biologist was taking off. Haeckel lived a long and eventful life, but no other event is as important to Richards’s interpretation as this one—Haeckel never gets over this loss. Darwinism fills the emotional void created by Anna’s death and merges with the rest of his intellectual background into a comprehensive worldview. Haeckel then wields his Darwinism with a vengeance against reassuring religious lies, but he can also find comfort in Darwin, along with new ways of seeing and loving the beauty of nature. (Very appropriately, the book conveys Haeckel’s aesthetic appreciation of nature vividly through color reproductions of his artwork.)

Haeckel would probably be gratified to know that his writings continue to provoke almost 90 years after his death, but he would also be dismayed at the staying power of many of the attacks on him. Richards comes to Haeckel’s defense, dispassionately dissecting the accumulated mass of negative literature to expose its errors and ideological biases.

Creationists, who still love to hate Haeckel, perpetuate misinformation about him, which Richards easily corrects. Embryologists have also been unhappy with Haeckel, because of the way he subordinates the study of ontogeny to his project of reconstructing phylogeny, and because of liberties he may have taken in some of his illustrations of embryos. Richards provides a good discussion of the competing disciplinary interests and their effects on Haeckel’s reception. He also seeks the proper historical standards of knowledge and visual presentation by which to judge the illustrations and to distinguish intentional fraud from other sources of inaccuracy.

Haeckel’s evolutionary view of ethics has been another lightning rod for criticism. Critics fall into two camps: militant theists, including creationists, who think there can be no moral standards that are not God-given; and those who, after World War II, wanted to trace the moral decline of Germany back into the 19th century. Both groups have given Haeckel a larger-than-life role in opening the door to Hitler or otherwise inspiring Nazi ideology, but Richards objects to these sorts of cautionary tales for both factual and methodological reasons. By 19th-century standards, Haeckel’s views on race were moderate, and in particular, he had an unusually high opinion of Jews. The Nazis themselves repudiated Haeckel and banned his books. And considering everything else that had to go wrong in Germany to result in the Holocaust—the complex of social, psychological and political developments that serious historians have been analyzing for half a century—it makes no sense to single out a 19th-century scientific writer as the crucial factor.

One particularly damaging line of attack on Haeckel stems from E. S. Russell’s classic work Form and Function (1916), which reduces Haeckel’s Darwinism to a combination of “dogmatic materialism” and “idealistic morphology.” Russell strongly connects Haeckel to a very negative picture of German Romantic Naturphilosophie and pre-Darwinian morphology, ascribing to them a penchant for constructing fanciful and hypothetical archetypes. To Russell there is no practical difference between such imaginary archetypes and imaginary common ancestors, or between Darwin’s theory and the discredited idealism. Although Darwin is now generally seen as breaking with idealistic morphology, Russell’s thesis is still widely applied to Haeckel, who supposedly clings to the old morphology and gives only anemic support to what is most novel and important in Darwin.

Richards quotes Russell disapprovingly both in his introduction and in his conclusion. He counters the charge of dogmatic materialism, but this is as far as his historiographic housecleaning goes. Indeed, connecting Darwinism with Romantic biology has been a hallmark of Richards’s work, only with a value judgment different from Russell’s. Richards has been a significant contributor to the ongoing reevaluation of Romantic science, and in his treatment the connection does not tarnish Darwin’s or Haeckel’s reputation, but rather vindicates the Romantics and shows how productive and inspirational their approach could be.

But what is Romanticism? An aesthetic appreciation of nature and a love of travel, painting and poetry are some common denominators among Richards’s Romantics. Most of them also have a certain pantheistic tendency to see God in or as nature. But more important to Richards is the Romantic notion that aesthetic judgment is required in the study of life. Animal forms are diverse and changeable, but beneath the unstable appearances, the Romantic expects to find underlying unity, purpose, and ideal forms or archetypes. These, the Romantic holds, cannot be seen directly or inferred logically but must be envisioned by the mind’s creative faculties. Similarly, organic change and progress must also be envisioned in terms of archetypal sequences.

Still, it seems to me that Romantic scientists do not form a very coherent group, especially not after the Age of Goethe. By the 1840s, Schleiden, for one, far from celebrating aesthetic judgment, was deriding Romantic botanists for their mystical and subjective fantasies. Richards has to erect a very big tent just to accommodate him, Goethe and Humboldt, and it is not clear how the men who taught Haeckel in the 1850s are supposed to fit in. Haeckel and Darwin get in for their travels, their aesthetic appreciation of nature and their admiration for Goethe or Humboldt. But why should we think that these few Romantic elements influenced or outweighed Haeckel’s and Darwin’s rejection of teleology in favor of historical contingency, or their rejections of archetypes in favor of common ancestors, idealized sequences in favor of ontogeny and phylogeny, and aesthetic judgment in favor of other methods of historical inference? Or does Richards, like Russell, mean to suggest that such shifts were insignificant or incomplete?

On the whole, I think he does not. When he compares Haeckel and Darwin directly, Richards makes it clear that the two agreed on key points. Their conceptions of common descent, heredity, variation and natural selection were similar; both men recognized the usefulness of evidence from morphology and embryology for reconstructing evolutionary history; and both rejected predetermined, teleological trends. Richards’s analysis brings Haeckel and Darwin closer together than ever before, even for those of us who resist making Romantics of them both. By doing so, and by defending Haeckel from the excesses of his critics and bringing out the personal side of his science, this book marks a major rehabilitation of Haeckel as a mainstream Darwinian, and a full-blooded one at that. It writes Germany into the larger story of the international development of Darwinism in a new way, and it injects welcome doses of drama, romance and natural beauty into the story.

Sander Gliboff is an associate professor and director of graduate studies in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at Indiana University in Bloomington. He is the author of H. G. Bronn, Ernst Haeckel, and the Origins of German Darwinism: A Study in Translation and Transformation (The MIT Press, 2008).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.