This Article From Issue

July-August 2006

Volume 94, Number 4

Page 371

DOI: 10.1511/2006.60.371

The Nature of Paleolithic Art. R. Dale Guthrie. xii + 507 pp. University of Chicago Press, 2005. $45.

I suppose it had to happen that someone would eventually write a book that took Paleolithic imagery to be "an immensely valuable archive for natural history." As theoretically questionable as this approach is, at least the culprit—R. Dale Guthrie, an emeritus professor of arctic biology at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks—is someone who knows his animals, both anatomically and ethologically. This fact is the saving grace of his book, The Nature of Paleolithic Art, which provides plenty of small gems of interpretation of animal behaviors and postures, some of them missed by previous generations of researchers.

If Guthrie had simply sought to expose nature in (and not the nature of) Paleolithic imagery, the book could have opened up some new windows and shed light on some old questions. Instead, however, he reacts with great energy against "the persistent sense that the really important questions to ask are connected with uncovering or detecting the meaning of images." According to him, "the traditional approach" has (mistakenly) sought clues to the "symbolism and ritual meaning hidden in the images." Researchers shouldn't be digging so hard for hidden significance, he insists, because "the art seems more focused on complicated earth-bound subjects, diverse everyday interests and wonders."

Archaeologists have long recognized that simply identifying the animals and animal behavior that are depicted on cave walls or objects is merely a point of departure for asking and answering more profound questions about ancient human culture. For example, these days no specialist in prehistoric art seriously believes, as Guthrie apparently does, that the problem of the meaning and motivation behind the painted ceiling of Altamira Cave (which dates to about 12,000 years ago) is resolved by identifying the species represented and their species-specific postures.

In some ways, this book returns us to an earlier era, when pioneers of the field argued that Paleolithic art was primarily a hunter's art. Abbé Henri Breuil (1877-1961), in particular, provided renderings of cave art that ignored most of the associated markings except those that resembled wounds, weapons or traps. In modern research, it is these long-ignored signs and markings that often provide insight into context and meaning. The hand silhouettes made about 27,000 years ago at Cosquer Cave (which is now partially submerged in the Mediterranean near Marseilles) are interesting—physiologically—as hands, and even as indicators of sex, age and handedness; but their symbolic significance is unmistakable when one recognizes that they were systematically overmarked and defaced by later Paleolithic painters. Hands, like animals, are the raw material of culturally embedded systems of meaning.

Today's researchers have consistently demonstrated that the animals most often represented in Paleolithic caves are among the ones least frequently consumed as food. The people who lived under the ceiling and in the cave entry at Altamira ate almost no bison, dining primarily on the meat of red deer (Cervus elaphus). Likewise, at Lascaux images of horses, bovids and red deer dominate, whereas reindeer, the primary dietary item in the food debris, aren't depicted at all.

In looking for answers to such questions as Why bison at Altamira? Why horses at Lascaux? and Why mammoths at Rouffignac?, researchers are propelled immediately into more profound matters of cosmology, belief and the relation of culture-bearing humans to the living world of which they are a part and to the mysterious world of the underground. As anthropologist Marshall Sahlins demonstrated 30 years ago in Culture and Practical Reason, the way we think about and represent animals speaks to questions that go far beyond their acquisition for food. This is as true of modern game hunters and traditional Inuit as it was of Paleolithic peoples.

Of course, the problem is how to explain why any of this animal world was graphically depicted, why our ancestors would have chosen to create images hundreds or even thousands of meters back from the cave entrances, why various subjects were arranged the way they were underground, why they are associated with particular acoustic qualities of caves, why some caves are chosen over others, why pictures engraved on portable objects are different from those on cave walls, and so on.

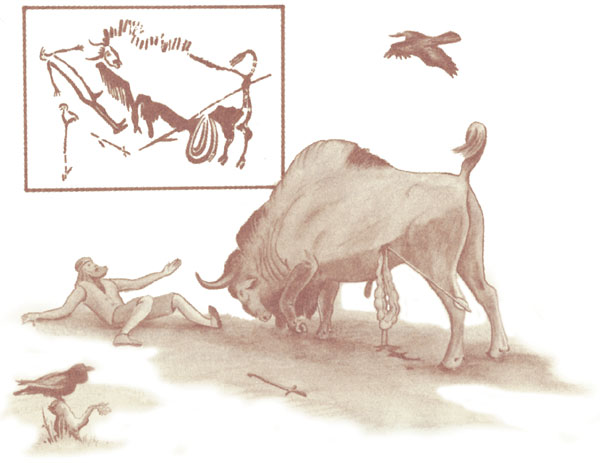

Disturbingly, Guthrie's book lacks any theoretical discussion of "art" and "meaning" in cultural or ethnographic terms. His ecological determinism leaves almost no room for metaphor, for the experiential power of caves or for a spiritual understanding of this underground world by ancient humans. Surely the fact that the horses at Niaux are 700 meters from the cave entrance is as important to understanding them as the fact that they represent animals in winter coat. Also, consider the engraved horse on a stone plaquette that was found at Etiolles in the Paris basin in an open-air Magdalenian campsite dating to about 12,000 years ago; a half-human, half-animal figure is following the horse (see illustration at right). Guthrie does not discuss this particular image, but it is the sort of thing that he would have difficulty asserting to be a page from a hunting manual. Interpretation of the object takes a rather different turn when one understands that the plaquette was found with the engraved face down, tucked beneath a limestone fireplace block. Context counts, and so does the world of human imagination and belief!

In spite of all of the above, the greatest problems with Guthrie's book are scholarly and methodological. As is the case with many recent American treatments of Paleolithic imagery, the list of references betrays limited mastery of recent foreign-language publications, especially by French, Spanish and Russian authors.

It is this language problem that leads Guthrie to overlook the details of pioneering works such as Léon Pales's detailed anatomical and ethological analyses of the La Marche engravings, and in particular Pales's wonderfully accurate drawings of the Magdalenian-period engravings from this key site in south central France. Guthrie (unlike Pales) leaves out of his own drawings precious details in order to promote his proposed readings. Surely it is important for the reader to know that the vast majority of the hundreds of animal and human images from La Marche were "defaced" by a mass of finely incised lines that make reaching an understanding of the original drawing an enormous visual challenge.

Guthrie's interpretations of Paleolithic images are expressed with a kind of certainty that approaches stridency. For example, his identifications of certain images as plants are made without reservation, even though the originals are notoriously ambiguous. He seldom provides alternative readings, and the fact that his drawings are not faithful to details and surface features prevents the reader from independently evaluating his propositions. The book does not contain a single photograph against which to judge the author's sketches.

From The Nature of Paleolithic Art.

It is not clear whether Guthrie viewed all of the original images and objects that he sketched, but I got the impression that foreign-language sources were mined for drawable images without due attention to the analyses in the accompanying text, which are sometimes identical to Guthrie's. He has redrawn all images in his own style without providing cultural attribution, without directing the reader to the original and without noting in the legend the actual size of the Paleolithic representation. He ignores context to such an extent that he does not inform the reader whether a given sketch he has made represents an engraving, a three-dimensional sculpture, a cave painting or a bas-relief.

Decontextualization permits Guthrie to pretend that Paleolithic representations ranging in length from one centimeter to more than five meters were, over a span of 30,000 years, stable, unchanging and unmodified by cultural changes, and that portable images from sites where people lived are the equivalent of paintings made deep in caves. Surely the fact that Gravettian female figurines (dating to between 28,000 and 22,000 years ago) are often buried in ritualized pits trumps their interpretation as universal examples of sexual presentation behavior. Guthrie's natural-history approach to women has been little softened by criticism of his 1984 paper "Ethological Observations from Paleolithic Art," in which he likened female figurines to the images in Playboy. Of course, that comparison underestimates the cultural context of both the figurines and the Playboy photographs.

The study of Paleolithic art has struggled over the years to become the rigorous and meticulous field that it is today. There is considerable food for thought and ecological insight in Guthrie's approach, and for that reason alone I am happy to have this book on my shelf. Unfortunately, its extreme ecological determinism, its lack of cultural and contextual sensibility and its failure to include images faithful to the original works make for a flawed enterprise.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.