This Article From Issue

November-December 2024

Volume 112, Number 6

Page 377

INTO THE GREAT WIDE OCEAN: Life in the Least Known Habitat on Earth. Sönke Johnsen. 248 pp. Princeton University Press, 2024. $24.95.

As an ocean-going, scuba diving scientist, I often invite students and collaborators along on research expeditions, some of whom are experiencing this habitat for the first time. As we submerge below the ocean’s surface and are surrounded by ocean animals, I am reminded of the profoundly small number of humans who have access or will ever get a glimpse of Earth’s largest habitat: the open ocean. I often wish it were possible to share this fascinating part of our planet with more people.

Sönke Johnsen achieves just that in his newest book, Into the Great Wide Ocean: He takes the reader by the hand and introduces them to life as an open ocean scientist, from the daily struggles and frustrations, to the life-altering joys and discoveries. Each chapter begins with personal stories that illuminate the life of an ocean-going scientist. These firsthand experiences then elegantly segue into descriptions of the physical world that animals experience, as well as their adaptations to counter these physical challenges.

Marlin Peterson

The chapters progress from describing physical phenomena that open ocean animals deal with—such as gravity, pressure, and light—and move to ecological interactions between animals, ending with a chapter on community. “Community” here refers to both the animals and the bonds among scientists that are strengthened by constrained quarters and shared goals during research expeditions.

Through the book, we come to understand and empathize with the complexity of the organisms and the communities that live in the blue expanse of the open ocean. This ecosystem comprises “winged snails that [fly] through the water like birds, long worms paddling with dozens of crystal oars, and 50-foot-long chains of tubular animals, each pumping to both suck in food and move through the water.” Though it is dazzling to imagine such strange and wonderful creatures, perhaps more intriguing are the array of strategies that these animals have for making their way in their watery worlds. As odd as their bodies and habits might seem to us, Johnsen reminds readers that “we are a water planet, and the rules of the oceanic realm are the primary rules of life. Our slender terrestrial world, and the rules that govern it, is the exception. To know the ocean is to know our planet.” Indeed, Johnsen’s aim is to show what it takes for these animals to live in the pelagic part of the ocean. He defines pelagic as “everything that is not the bottom, which includes the surface and the watery world between it and seafloor.”

As a visual ecologist, a scientist who studies how animals use visual systems for their survival needs, and marine biologist, Johnsen has devoted much of his career to understanding how light behaves in water, as well as how light is perceived by undersea animals. His lifelong fascination and experiences studying the myriad ways that animals’ lives are governed by light emerges in his detailed descriptions of both straitlaced physics and the nuanced ways that animal physiology responds to it. One mind-bending example is that in order to “hide” in the open ocean, some transparent shrimp essentially hold their breath when resting so as not to fill their vessels with blood. Johnsen explains, “Shrimp blood is clear, but it still scatters light, so keeping the vessels empty makes the animal clearer.”

Light also behaves differently underwater than in air. The different wavelengths penetrate to different depths, and “these differences in how different colors travel through water really pile up when you have a lot of water. This is because the light level is an exponential function of depth rather than a linear one.” Researchers visiting the open ocean have a very different sensory experience than the animals that have evolved in this context. Because short wavelengths, like blue, penetrate furthest, while longer wavelengths, like red, attenuate more quickly in surface waters, pelagic organisms have evolved in a predominantly blue world. It also gets much darker even in relatively shallow water than it does on land. This darkness sets the stage for visual adaptations in the open ocean.

We are a water planet, and the rules of the oceanic realm are the primary rules of life.

Animals have solutions to darkness that include spherical lenses that focus light at different distances by having a continuum of different densities, mirrored eyes that bounce light around to increase the odds of detection, or simply having bigger eyes that catch more light. But every solution comes with trade-offs. Animals have adapted various solutions like having eyes that are very close together in the middle of the head, or having tubular eyes, but the trade-off here is that “they get the advantages of a big pupil and lens, but at the expense of not being able to see in all directions.” Readers are reminded throughout Into the Great Wide Ocean that such trade-offs are the price of adaptation.

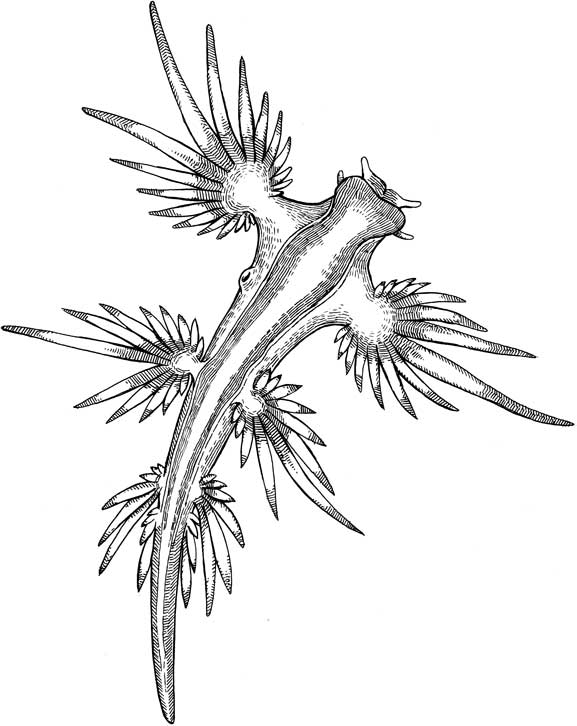

Throughout the book, descriptions of pelagic animals are supplemented by realistic line illustrations, drawn by artist Marlin Peterson. Some of these creatures can best be described as animals that only a mother could love, except that in most cases, their mothers can’t see and will never come into contact with their offspring. The illustrations showcase the beautifully strange animals that evade literary description. Pelagic animals are not comparable to anything we witness in our day-to-day lives—pteropods, for example, are flying snails that have mostly lost their shells—so the visuals are a welcome addition.

Detailed scientific descriptions of how marine animals go about their lives are punctuated by the retelling of transcendental moments that invariably reveal themselves when one spends hours submerged in the open sea. Johnsen compares his first open ocean dive in the Gulf of Mexico to “falling like slow-motion sky divers in a blue sky that had no earth below.” He writes: “Soon it was obvious that we were surrounded by translucent beings of all kinds, shapes, and sizes, ranging from 30-foot-long trains of a colonial animal known as a salp to pinkish moon jellies that were a foot across. While a few smaller animals seemed to be fighting their way upwards . . . for most it was as if gravity didn’t exist at all. As if we were in outer space, between the galaxies, but everything was lit with blue light.” This description conjures a stunning visual that takes on even greater significance when he concludes with, “It was the most astonishing thing I’d ever seen, and its memory still sits with me like a first kiss or the birth of a child.”

Most of us don’t have any idea about what it’s like to be a scientist in the middle of the open ocean, and we are even more challenged to imagine what it’s like to spend a life entirely underwater. Indeed, even the most dedicated researchers get only a brief glimpse into the vast worlds they are studying. Johnsen’s detailed personal experiences put us there for a little while. His intimate descriptions of pelagic organisms achieve his stated goal: “Before we as scientists can ask people to preserve this important and fragile habitat, we need to show them that it’s there and the beauty of what lives in it.”

Johnsen acknowledges the reality of spending only a couple of weeks at sea or scuba diving each year, and how even then, life at sea can be stressful, with too little sleep and involving too many late-night candy bars and rolls of duct tape. (Duct tape is used when high tech equipment at sea invariably breaks or equipment gets wonky and scientists have to get resourceful.) It’s the endless preparation, drudgery, and lost sleep that, in part, make the highs so high for a seagoing scientist. Beyond the science, it’s also the sharing of discoveries, however minute, with students and collaborators that make the effort worth it. The discipline of oceanography, especially oceanography at sea, is extremely team-oriented, as Johnsen reminds us throughout Into the Great Wide Ocean. “We want to be in a group where what we do matters. Many of us spend our lives looking for this, or—if once we had it—finding our way back. And those of us who find it at sea come back again and again.”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.