This Article From Issue

November-December 2005

Volume 93, Number 6

Page 559

DOI: 10.1511/2005.56.559

Master Mind: The Rise and Fall of Fritz Haber, the Nobel Laureate Who Launched the Age of Chemical Warfare. Daniel Charles. xx + 313 pp. HarperCollins, 2005. $24.95.

Master Mind, Daniel Charles's new biography of chemist Fritz Haber, can be read with profit by knowledgeable scientists and informed laypeople alike. Comprehensive and even coverage of Haber's eventful, tragic life and informed description of his scientific achievements and their economic and military implications are the book's greatest strengths. Charles does a good job of setting Haber's family background, career, marriages, acquaintances, and scientific and managerial achievements in wider historical, political and economic contexts. Charles, a former correspondent for National Public Radio and the author of a book on biotechnology in agriculture, has done his homework well. He draws primarily on a wealth of documents (now at the Max Planck Society in Berlin) that were gathered for Johannes Jaenicke's intended, but never finished, biography of Haber.

In his preface Charles makes much of the notion that Haber, despite the enormous impact of his work, is a "forgotten scientist" who has disappeared from view. But engineers and scientists in many disciplines (chemistry, physics, agriculture) never forgot Haber's accomplishments; how could they? And the public has no memory of scientists anyway, except of course those few who reach celebrity status. Consequently, an average American or German recognizes the name of Einstein but knows nothing about Otto Hahn (to use two of Haber's Nobel Prize-winning colleagues as examples). Yet Hahn was a codiscoverer (with Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann) of nuclear fission, thus initiating the nuclear age, with its dual legacy of fears of mass destruction and promises of carbon-free energy.

Haber's scientific work similarly had a destructive as well as a constructive side: His discovery of how to synthesize ammonia from its elements led to nitrate-based explosives and gas warfare as well as to nitrogen fertilizer, and he supervised Germany's use of chemical warfare in World War I. Charles's presentation of both the positive and negative aspects of Haber's achievements is accurate, informative and balanced.

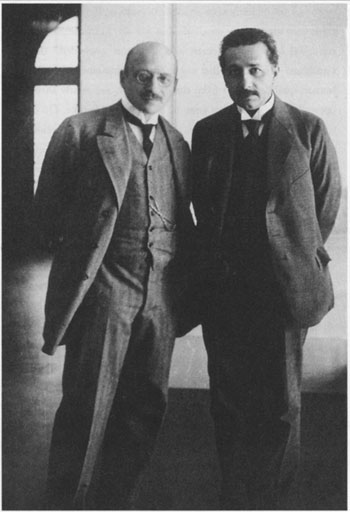

From Master Mind.

Charles (relying heavily on the writings of historian Fritz Stern) gives particularly extensive attention to Haber's complex relationship with Einstein, whom he brought from Zurich to Berlin's Dahlem research institute. The book contrasts the attitudes that the two men assumed vis-à-vis the place of German Jews in Germany. Haber, who converted to Protestantism in 1892, was a convinced German patriot. Einstein never felt that sort of affinity to Germany, and his letter to Haber, after the Nazis forced him out of his position at Dahlem in 1933, sounds more like I-told-you-so than an expression of sympathy: "It is somewhat like having to abandon a theory on which you have worked for your whole life. It's not the same for me because I never believed it in the least."

In contrast to this expansive treatment of Haber-Einstein interactions, short shrift (a mere two pages) is made of one of the most curious periods of Haber's life, his failed quest for the extraction of gold from seawater. That pursuit occupied more than five years of his life and was intended to solve the burden of Germany's onerous reparation payments after World War I.

Another minor complaint is that Charles is fond of journalistic labels. Let me give just four examples, two from the preface and two from the book's penultimate page: "Haber was the patron saint of guns and butter"; "Haber lived the life of a modern Faust"; "Haber's blond beast of progress still roams the globe"; and "Haber, a prophet of progress." A more serious concern is that Charles tends to extend some of the causal lines indefensibly far. Standing at the cemetery at Ypres (the site of the first German chlorine attack in April 1915), Charles hears a military jet and concludes that "This high-tech aircraft . . . represents the true legacy of Fritz Haber the gas warrior" because "the marriage of science and military power has endured. And its spiritual lineage leads back to Dahlem." And to a myriad of other beginnings and preconditions!

Charles's speculations about the historical impact of Haber's work are even more questionable. Undoubtedly, large-scale nitrogen fixation severed Germany's dependence on imports of Chilean nitrates and helped to prolong World War I by providing a secure feedstock for munitions, but this fact in no way means that "in the absence of Fritz Haber, in other words, we might never have heard the names Hitler and Stalin." This claim is about as valid as saying that we might never have heard about them if Hitler had succeeded in becoming a second-rate architect in Vienna before World War I and if Stalin had completed his training in the orthodox seminary in Tiflis and had spent his life as a Georgian priest.

Haber's fate attracts us because of its contradictions and its tragic ending. We have his scientific writings, his patents, his lectures on science and research management, many of his letters, numerous recollections of his colleagues and students, and the memoirs of his second wife. But we will never know the actual mix of motives that animated his life and the deepest feelings that marked both his ascents and falls. Only in a few of his letters did he offer unguarded self-appraisal. Everything else, including his feelings about the suicide of his first wife, he kept to himself. We will never truly know him.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.