This Article From Issue

January-February 2024

Volume 112, Number 1

Page 3

DOI: 10.1511/2024.112.1.3

Henry Petroski

To the Editors

I read the letters from the readers of my husband Henry Petroski’s American Scientist Engineering columns with tremendous pride. Even as he approached the 200-column mark, Henry was still full of ideas, some of them sparked by letters from the column’s readers. Over the years, his correspondence with so many readers was a source of great joy to Henry, and he looked upon his readers as extended family. Readers’ letters were part of a stimulating dialogue that Henry cherished. How gratifying it is to know that the feeling appears to have been mutual.

Henry’s family and I thank the editors for the tribute of retiring the Engineering column in his honor and for sharing the readers’ letters.

Catherine Petroski

Durham, NC

Cosmology

To the Editors:

In her review of On the Origin of Time: Stephen Hawking’s Final Theory by Thomas Hertog (“A Quantum History of Space-Time,” Nightstand, November–December 2023), Chanda Prescod-Weinstein relates being asked with regards to cosmology, “How is that useful?” If indeed, as Prescod-Weinstein notes, “physical systems do not have a deterministic evolution,” the answer is right there hiding in plain sight.

The deepest practical question facing our species concerns the origin of the universal emotional sickness which has manifested throughout recorded history as war, crime, racism, misogyny, poverty, and unhappy personal relationships. As we avoid seriously confronting this problem, we assure ourselves that the quest is unworthy because the misery is foreordained by the past. Whether determinism takes the form of physical theory, or of the ancient Abrahamic notion of original sin, is irrelevant. The two ideologies are functionally identical.

The Zen koan of the monk who became a fox after teaching that the enlightened person is not subject to cause and effect is illustrative. To have asserted the opposite would be equally misleading. To personally live (not merely assert) the truth that free will grows on a substrate of determinism is immensely difficult. If quantum cosmology casts doubt on the absolute nature of determinism, that is a valuable tool in the exponentially more difficult quest of the human species coming to its senses.

Jeff Freeman

Rahway, NJ

Definition of Direct

To the Editors:

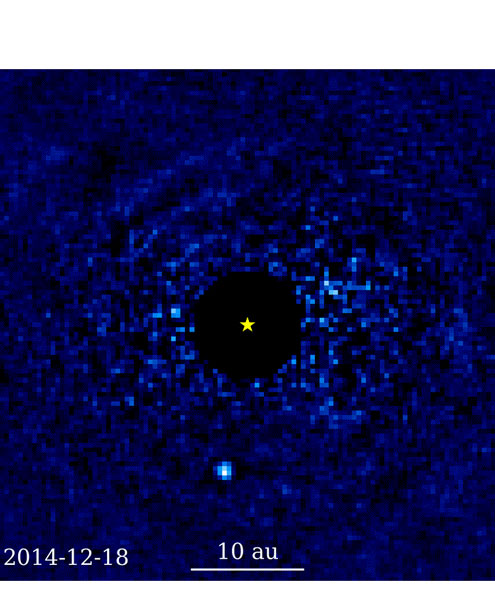

I am astonished to read that Marija Strojnik (“Direct Detection of Exoplanets,” September–October 2023) states that we have not yet and cannot directly image exoplanets. This is demonstrably incorrect. NASA/IPAC has a list at exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu/docs/imaging.html.

One example is an image of 51 Eridani b. The planet is 2.6 times as massive as Jupiter and has the same radius. Charitably, one may make the excuse that most of these images are of planets slightly more massive than Jupiter, but most are at best marginally larger in diameter.

Gerard Kriss

Emeritus Astronomer

Space Telescope Science Institute

Dr. Strojnik responds:

I am pleased that my article brought a response. The phrase planet detection evokes in people’s imaginations beautiful images of planets that are creative artistic representations of novel worlds. But a single fuzzy smear of brightness amid so many other smears of brightness is not an image, not even in astronomy or astrophysics. Not even when it is distributed over several pixels.

Exoplanet researchers routinely call videos such as the one below of 51 Eridani b “direct images” because the planet’s light has been separated from that of its star. “Directly imaged” is the standard language of exoplanet astronomy. But to an optical scientist such as myself, there is a strong distinction between direct detection (the planet’s light disentangled from the light of its star) and direct imaging (a resolved picture of the exoplanet). From an optical researcher’s perspective, a single pixel simply is not an image. Spectroscopic analysis can be done on that pixel, but it remains an unresolved spot.

Jason Wang (Caltech)/Gemini Planet Imager Exoplanet Survey

Indeed, even the word direct in direct detection is debatable from an optical researcher’s point of view. The detection of the light of the exoplanet requires significant processing, adding multiple images and subtracting starlight based on theoretical models of the source signal.

But the interpretation of a bright pixel as a planet is only possible upon visual inspection and optimistic thinking, in reference to other, selected frames. The detecting instrument records the diffraction patterns of its own aperture upon illumination with two point sources in infinity—the star and the planet. Then the image of the star is digitally subtracted pixel-by-pixel up to half the distance to the exoplanet, that is, far beyond Mars. Why so far? The concentric rings, along which the brighter pixel is moving, are not planetary railroad tracks. Rather, they are the regions of the image that the detecting instrument recorded of the star (point) object that the creative image-digitizer chose not to, was not able to, or did not dare to erase.

The sequence of frames that represent 51 Eridani b have been selected from a tremendously large number of frames—three to four years’ worth of them—and then selectively processed, including different normalization of each frame. The environment around the star edge is for some parts of the sequence much brighter than the pixel that represents the so-called planet. As an optical scientist with specialization in infrared, I cannot look at a single frame in this sequence and call it an image of anything but a very noisy diffraction pattern of a point source, with the central part erased. This does not mean that the work is not a great piece of detailed frame-processing and data selection. But a trajectory, or a sequence of bright points, is not an image of a planet, although it very likely represents something that nowadays is denoted as an exoplanet.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.