This Article From Issue

September-October 1998

Volume 86, Number 5

DOI: 10.1511/1998.37.0

Frankenstein's Footsteps: Science, Genetics and Popular Culture. Jon Turney. 270 pp. Yale University Press, 1998. $30.

What is it that persistently leads the public to equate experimental science, especially in biology or genetics, so automatically with Dr. Frankenstein and his monster? In this thought-provoking treatment, Jon Turney demonstrates that Mary Shelley's classic novel and the myth it spawned have provided images incorporated into popular debates about advances in biology from the early 19th century to the contemporary furor over genetic engineering. Although Turney provides one truly significant reason for the public's enduring fascination with the Frankenstein myth, along the way he misses many opportunities to show the influence of Shelley's creation on a number of 20th-century texts that deal with the biological revolution; instead, he prefers to spend almost half the book tracing echoes of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World in the popular press (a curious strategy, considering his title). He also misses what is, to my mind, a central reason why Frankenstein has so effectively shaped our culture's view of the scientist.

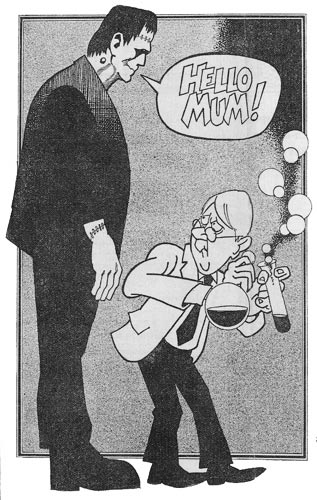

From Frankenstein's Footsteps.

As a first significant text of modernity, Turney points out, Frankenstein centers on a concept that was revolutionary in Shelley's day: the violation of the integrity of the human body itself. Shelley envisioned, Turney says, "right at the start" of the modern era, "a science working on the body to transform it, a science which might one day come to pass. Now that we are indeed building such a science, we can see that it has always been a part of the modern project." Transformation of the body through invasive manipulation is a key insight, a critical reason for the ambivalence Turney sees in public responses to biologists and their work. Most people have a sense of the extraordinary potential of contemporary biological and genetic research, yet they continue to worry about scientists' invading—and, perhaps, transforming forever—the body, the very seat of human identity itself.

From Mary Shelley's day to our own, this ambivalence has been a remarkably consistent feature in popular discussions of biological research. Turney makes this point through exhaustive references to newspaper accounts and less-exhaustive references to popular culture narratives. Journalists Turney cites applaud virtually all advances in all the sciences, not just biology; meanwhile, they take significant pains to reassure the public that Frankensteinian consequences are highly unlikely. Editorialists and fiction writers, on the other hand, often exploit moral or religious fears. Turney quotes a particularly revealing example from the London Evening News, which "declared that most people found the notion of man-created life distasteful, blasphemous, and suggestive of meddling with forbidden things."

We are, of course, in similar straits today, with activists, writers and others treating genetic engineering as an affront to nature. For instance, characters in Jurassic Park blithely predict only disastrous results from manipulating dinosaur DNA. Nonetheless, I cannot believe such alarmist rhetoric reflects the beliefs of most reasonable people. Surely no reasonable person can condone the idea of turning our backs on the vast potential of genetic research. Of course, the invasive nature of this revolutionary technology-in-the-making leads the public to worry about its capricious or uncritical application, as Turney rightly points out. I suspect the public will come around; effective treatments or cures for illnesses such as genetically implicated cancers will do the trick. Meanwhile, after uncounted reassurances regarding the safety of advanced biomedical research, after myriad accounts of its glorious possibilities, the public is persistently ambivalent, about not only about applications but also biological experimentation itself. Why?

My suspicion is that the public is worried about something Turney barely touches on: human nature. I have noticed that my students—and even influential professional critics—almost unanimously agree that Victor Frankenstein, not his creature, is the true villain. These readers argue that fundamental moral lapses in Frankenstein the scientist implicate him as a primary cause for the catastrophes that overwhelm his family. He undertakes his project not for altruistic reasons, not to advance human knowledge, but primarily for the glory it will bring to him, and he isolates himself from his family and loved ones. Like an abusive father, Frankenstein rejects his own creation. Victor decides that malice is the monster's sole motivation, and he destroys the female companion the monster has begged him to create. This decision leads directly to the deaths of Victor's best friend, his bride and his father, and it causes Victor to devote the rest of life to a fruitless quest for revenge.

Turney has little to say about Victor Frankenstein the flawed human being, yet this characterization, I believe, is a major reason the Frankenstein story still grips us. Shelley tapped into a fear that scientists, being venal human beings, will not be wise or responsible enough to control their potentially deadly creations—hence, the renewed vigor of the popular figure of Dr. Frankenstein in debates over such fundamentally transformative technologies as genetic engineering. Certainly, genetic engineering holds revolutionary promise for improving our lot, but, the Shelleyan anxiety whispers, can any human being be trusted to manage it?

Here, Victor Frankenstein, not his creation, drives the metaphors. And it's not just the novel's Victor Frankenstein. Many people gain their understanding of the Frankenstein myth solely through experiencing popular media, and it is a flaw of Turney's book that he nearly ignores these retellings of the story. Had he carefully examined Frankensteinian popular cinema, Turney would have seen that the scientist, not the monster, is portrayed as the greater threat to middle-class ethics and sensibilities. In Bride of Frankenstein, Frankenstein follows the siren call of Dr. Praetorius to engage in more and dangerous research, to the neglect of bride and home. Later, in Hammer Films' influential retellings of the story, Frankenstein, played by Peter Cushing, coolly treats human relationships solely as a means toward his research ends. The monster is frequently only a tool, a puppet manipulated by unscrupulous characters; scientists are to blame.

This is an issue Turney should address. He takes note of scientists' complaints about "anti-science hysteria" or about wild public speculations regarding very unlikely consequences of experimentation. And these are, as he shows, by and large misplaced anxieties. Still, Mary Shelley and her countless imitators are asking an additional question, a slightly different one. They voice worries about experimental science, yes, but more fundamentally, they voice worries about the experimental scientist. Mary Shelley worries that experimental scientists, like all human beings, may be too prone to ego-gratification, self-centeredness, obliviousness to the implications of their actions and a tendency to shirk moral responsibility.

Still, there is cause to be optimistic that this ambivalence will evolve into wholehearted support. Turney points out that funding for human-genome research in the United States and Great Britain now involves modest support for "ethical, legal, and social studies of the new genetics." It is a small but essential step toward showing the public that scientists are as concerned about the wisdom of their research as they are its practicality. It also shows that the Frankenstein myth should no longer be the automatic response toward the whole of science. Turney hopes that we shall come to this exact conclusion. I think we are on our way.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.