This Article From Issue

January-February 2014

Volume 102, Number 1

Page 71

DOI: 10.1511/2014.106.71

THE SCIENTIFIC SHERLOCK HOLMES: Cracking the Case with Science and Forensics. James O’Brien. xx + 175 pp. Oxford University Press, 2013. $29.95.

MASTERMIND: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes. Maria Konnikova. xii + 273. Viking, 2013. $26.95.

Somewhere amid the zombies and vampires, the superheroes and fairy-tale creatures, Sherlock Holmes is having a moment. Exhibits A through D: Surly, painkiller addict Dr. Gregory House of the recently departed Fox series House MD. Asocial, nicotine-infused Sherlock Holmes of the BBC series Sherlock. Cranky recovering addict Sherlock Holmes of the series Elementary. And the peculiar, cocaine-sampling Sherlock Holmes of the eponymous Guy Ritchie film. These inspired eccentrics all rely on ingenious flights of reasoning to make deductions with astonishing accuracy. The cultural tenacity of Arthur Conan Doyle’s most famous character more than 125 years after he first appeared in print might have confounded the great detective himself.

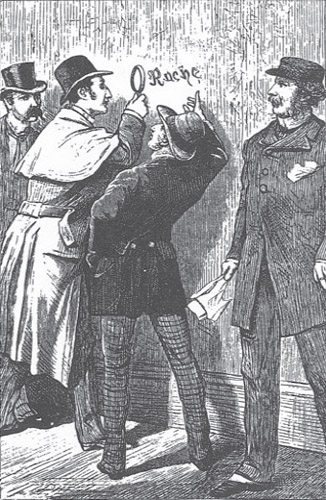

From The Scientific Sherlock Holmes.

Some of the reasons for Holmes’s popularity today may not be so different from those in the 19th century. The scope of cultural change spurred by the Industrial Revolution resembles that of our own era’s rapid technological transformation. Media coverage of crime during the Victorian era had a feverish tone and ubiquity that is familiar today. (For more on this morbid fetish, see Judith Flanders’s engrossing 2011 book The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime.) In the 21st century we remain intrigued, even comforted, by the notion that, with a stockpile of knowledge and solid reasoning skills, we may stare at apparent chaos and discern patterns that will enable us to sort legitimate fears from unfounded ones, to dispatch justice where injustice has ruled, to find answers where certainty had seemed impossible.

The Holmesian intellect itself comes under close scrutiny in two recent books. In The Scientific Sherlock Holmes: Cracking the Case with Science and Forensics, James O’Brien examines the scientific knowledge involved in Holmes’s deductions, its degree of accuracy, and its importance to the stories. In Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes, Maria Konnikova analyzes the habits of mind that aid Holmes in his work and proposes how those among us who are not professional consulting detectives may apply them.

O’Brien’s book is more overtly academic, studded with citations and the formal organizational trappings of a monograph. In the style of his subject, O’Brien conducts a thorough investigation, one informed by a wealth of scholarship on the Holmes stories. He prepares the reader with background information on Holmes’s origins and Conan Doyle’s influences, as well as with a refresher on the main characters. Then he digs into the science with an extensive discussion of Holmes as a pioneer of forensics, taking up topics like document analysis—going so far as to detail evidence from the two Holmes tales in which ink blotters provide a clue—and the use of dogs in crime solving. O’Brien also provides historical context for early fingerprint analysis. Holmes’s use of fingerprints in his deductions for such cases as “The Sign of Four” in 1890 (the first instance among several) would have made him an early adopter of this cutting-edge Victorian forensic science. Pleasingly, O’Brien includes a nod to Mark Twain’s earlier mention of fingerprint evidence in Life on the Mississippi in 1883 and his use of it again in 1894 as a critical plot device of Pudd’nhead Wilson, his excellent novel of deduction, identity, culture, and race.

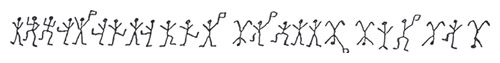

From The Scientific Sherlock Holmes.

Especially entertaining is the section on cryptology, where O’Brien describes various methods of code making and presents brief histories of some actual cases featuring coded messages before investigating cryptology in the Holmes stories. Conan Doyle acknowledged the influence of Edgar Allan Poe’s story “The Gold Bug” and its coded message of hidden treasure. Poe was a cunning cryptographer: O’Brien reminds us that Poe created two codes solely for his readers’ amusement, each of which took a full 150 years to crack. O’Brien conducts a side-by-side comparison of Poe’s and Conan Doyle’s styles of creating ciphers for, respectively, “The Gold Bug” and “The Adventure of the Dancing Men,” both of which use a substitution code solved through frequency analysis. Conan Doyle scores points for clarity of presentation and the accuracy of Holmes’s linguistic knowledge of letter-use frequency. Nevertheless, Poe wins in the category of overall precision. When it first appeared, Conan Doyle’s “Dancing Men” code (see example above) used a figure for the letter V in the fourth message that represents P in the fifth.

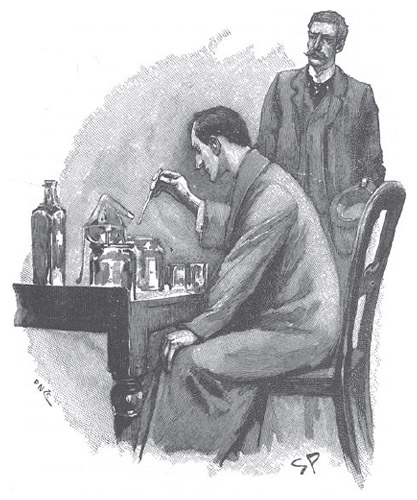

O’Brien devotes a full chapter to the importance of chemistry in the tales of Sherlock Holmes, and in the very definition of the character. Holmes’s “first love was chemistry,” according to O’Brien, who notes, “Only chemistry can lure him from one of his cases.” The role of chemical poisons, coal tar derivatives, and acids (among other chemicals) in the stories is fascinating, as is the discussion of the mystery chemical used in The Hound of the Baskervilles that transformed the titular hound, “outlined in flickering flame,” into a nighttime terror. In the story, Holmes suggests it may have been an especially inventive preparation of phosphorus, as there was no phosphoric odor; Holmes scholars have suggested a number of more plausible options, such as barium sulfide, that could have produced the same effect.

From The Scientific Sherlock Holmes.

The Scientific Sherlock Holmes comes into its own most clearly when taking on the famous criticisms of Holmes as chemist that were leveled by the famed science and science fiction writer Isaac Asimov, who was himself a chemistry professor and Holmes scholar. O’Brien seems to relish the opportunity to answer Asimov’s claims. He gathers an array of scholarly views about each and then, in his own response, mines the historical context of chemistry as it was practiced during Conan Doyle’s time. In the end, O’Brien’s views are more aligned with Asimov’s than against them, but he illuminates and elevates the discussion—after all, it is only reasonable to consider Holmes’s chemical terminology, experiments, and analyses in keeping with the state of the science in his own time.

The real shortfall, O’Brien argues, is the stories’ diminishment in quality over time as Holmes’s interest in chemistry—as well as the other sciences—wanes. O’Brien points out that all seven tales in which the Baker Street detective conducts chemical experiments are found in the first half of the 60 works that are together considered the Holmes canon. Mention of other sciences drops off similarly, if not as dramatically, across the tales. Is it coincidence, O’Brien asks, that survey after survey of Holmes readers locates the most popular stories squarely in the first half of the canon? He thinks not. “Science lent a robustness and complexity to the stories,” he notes, observing that a detective “who applied the scientific method actively would challenge readers’ faculties…with a resourcefulness that, although occasionally improbable, was never impossible.” He wonders, as Conan Doyle himself evidently did early in his career, whether readers could find detective work ultimately plausible if it was unencumbered by science.

Underlying the wealth of knowledge that O’Brien finds crucial to the stories are habits of mind long steeped in the scientific method. The habits themselves are the focus of Maria Konnikova’s book Mastermind, which presents mental methodologies intended to help readers achieve Holmeslike insights and deductions. Throughout the book she deftly interweaves examples from the Holmes stories with findings from contemporary psychological research to support her points about topics like the role of interest and motivation in encoding and consolidating memories.

But when something goes wrong—when failure results, despite one’s devotion to the scientific method—what then?

Konnikova’s examples are remarkably instructive, particularly when she goes into depth, as she does in teasing apart the strands of Dr. Watson’s impressions of Mary Morstan on first meeting her in The Sign of Four. After discussing potentially mitigating factors such as implicit bias, she contrasts Watson’s impressions with Holmes’s based on the same meeting. Konnikova draws our attention to Holmes’s reaction when Watson notes Morstan’s physical attractiveness. Holmes declares the observation “irrelevant,” instructing his friend, “It is of the first importance not to allow your judgment to be biased by personal qualities. A client is to me a mere unit, a factor in a problem. The emotional qualities are antagonistic to clear reasoning.” Konnikova explains that in thinking like Holmes, “it’s not that you won’t experience emotion. Nor are you likely to be able to suspend the impressions that form almost automatically in your mind.…But you don’t have to let those impressions get in the way of objective reasoning.” Holmes’s awareness of his biases, she argues, enables him to compensate for them in his deductions.

Konnikova’s mantra is that we should be guided by the scientific method in our habitual thought processes. As a starting place, she recommends learning, honing, and applying shrewd observational skills. She instructs us to draw on those observations in approaching a problem, as well as on a store of knowledge and experience, and engage the imagination to generate hypotheses. The final step is to test them one by one until all the implications are known, at which point an apt conclusion inevitably appears. Konnikova emphasizes the importance of continuing to learn, retest, and practice these skills to remain sharp and to prevent being overtaken by change.

But when something goes wrong—when failure results, despite one’s devotion to the scientific method—what then? Here the discussion becomes most interesting, as Konnikova uses Holmes’s inaccurate theories in “The Adventure of the Yellow Face” as a riveting case study on overconfidence. In the story, Holmes is working on a case in Norbury when his record of success at last goes to his head and he confidently but incorrectly deduces the identity of the mysterious yellow-faced character. That pattern is all too typical in certain conditions, according to the studies Konnikova cites. Specifically, as a problem’s difficulty, familiarity, or background information increases, overconfidence is likely to surge, as it also does when the subject becomes more actively engaged. Awareness of these conditions and their possible consequences can forestall overconfidence and its negative effects, however, as Holmes recognizes in the story. Konnikova notes his request as his work concludes in “The Yellow Face”: “Watson, if it should ever strike you that I am getting a little overconfident in my powers…kindly whisper ‘Norbury’ in my ear, and I shall be infinitely obliged to you.”

In addition to the scientific and behavioral insights presented by these two books, they offer the reader an opportunity for fresh literary perspective. For the Sherlockian (or Holmesian, the preferred term on the detective’s home soil, O’Brien notes), the extensive examples drawn from the canon thread the tales together in unexpected ways, based on commonalities like the use of footprints in a plot point. Contours and shadings reveal themselves more clearly, like adding a gallery light to a familiar painting. For readers less familiar with the tales, their enduring appeal is thrown into relief. The characterizations and plotting are undeniably ingenious, their cleverness all the more evident when viewed in historical context. O’Brien’s and Konnikova’s deep engagement with Sherlock Holmes is so infectious that readers may soon find themselves digging into, or back into, Conan Doyle’s stories. For any text that turns its lens on the famous detective, such a consequence is the highest compliment of all.

Dianne Timblin is interim book review editor for American Scientist and author of the poetry chapbook A History of Fire (Three Count Pour, 2013).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.