This Article From Issue

September-October 2013

Volume 101, Number 5

Page 322

DOI: 10.1511/2013.104.322

You just have to know what to look for. That is a common explanation scientific experts give when trying to describe how they get their results—whether the process in question involved locating an animal in the wild or searching for a gene in the lab. There is also an important corrolary to that explanation: You have to know that there’s something to look for in the first place. Often, stepping out of your own perspective and trying to see through the eyes of others is a good way to see what might have existed all along but escaped your notice.

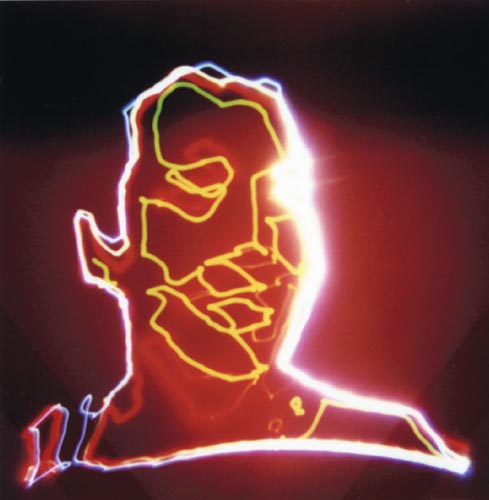

The picture above is a good example. That’s what I look like when viewed by a robot. The image was created by an MIT art project called Fotron2000, which uses facial recognition technology to determine where features are located. A robot arm equipped with an LED then traces its interpretation of the face onto Polaroid film. The creators of Fotron2000 say they wanted to have gallery visitors “engage robotic technology in an impractical way,” but the image reminds me that others may see the world very differently than I do.

This issue of American Scientist offers many opportunities to open your eyes. James Carter’s photoessay on “Flowers and Ribbons of Ice” introduces a remarkable phenomenon that few people have heard about, let alone seen for themselves. This winter, many of our readers may be hiking out into the woods at dawn to observe these elusive frozen formations.

Simson Garfinkel’s article, “Digital Forensics," takes on information that is hidden in plain sight. Forensic experts routinely recover “deleted” files from electronic devices, and acquire data based on quirks in computer systems that even the developers didn’t know existed. The resulting evidence is increasingly important in prosecuting criminal cases.

Sometimes the best way to step out of your comfort zone is to take on a project in which you have no expertise. In “Citizen Science Takes Root," Kayri Havens and Sandra Henderson describe the work of volunteers who help collect data even though they have no formal training in science. This brigade of citizen scientists is having a substantial effect on the understanding of Earth’s changing environment.

If your vision is poor, it is all the harder to take a new look at what’s going on around you. The revolution of corrected eyesight is the topic of Henry Petroski’s Engineering column in this issue. Although the original inventor of eyeglasses is lost to history, Petroski details some of the fascinating milestones on the road to modern eyewear.

This issue’s Technologue column takes us back to the subject of robots—ones that show up in an unexpected location. Most robots are used in industrial settings, but as Stephen Piazza describes, they can free humans from exhausting labor in other ways as well. In this case, robots have a role in physical therapy—helping patients who need to learn to walk again.

There are plenty more examples of eye-opening information in this issue, but we want to leave you free to do your own exploring. Let us know what expanded your worldview, or share some perspectives of your own.

Finally, with this issue we welcome the new interim editor of American Scientist, Corey S. Powell. Corey, the former editor-in-chief of Discover, is taking the helm from retiring editor David Schoonmaker. Although Corey is dedicated to maintaining the traditions and exacting quality of American Scientist, his new perspective will also be reflected in the pages of the magazine. We look forward to seeing our world in a new light, and hope you enjoy the fresh view as well.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.