What the Public Really Thinks About Scientists

By Cary Funk

Surveys show a desire for greater transparency and accountability in research.

Surveys show a desire for greater transparency and accountability in research.

Trust is an easy concept to grasp but a difficult one to quantify. Like scientific findings, trust in science is also tentative and subject to revision. The degree to which the public trusts scientists as a group is one key indicator of the quality of the public’s relationship with science, and in this sense, trust can be quantified. Surveys can assess public attitudes toward scientists and track how those attitudes change over time. Over the past year, scientists and their work have been at the forefront of public discussions about how to handle the coronavirus outbreak and how to develop effective treatments and vaccines for the disease. Those events might be expected to affect public trust in science. A group of us at the Pew Research Center collected data to measure any impacts.

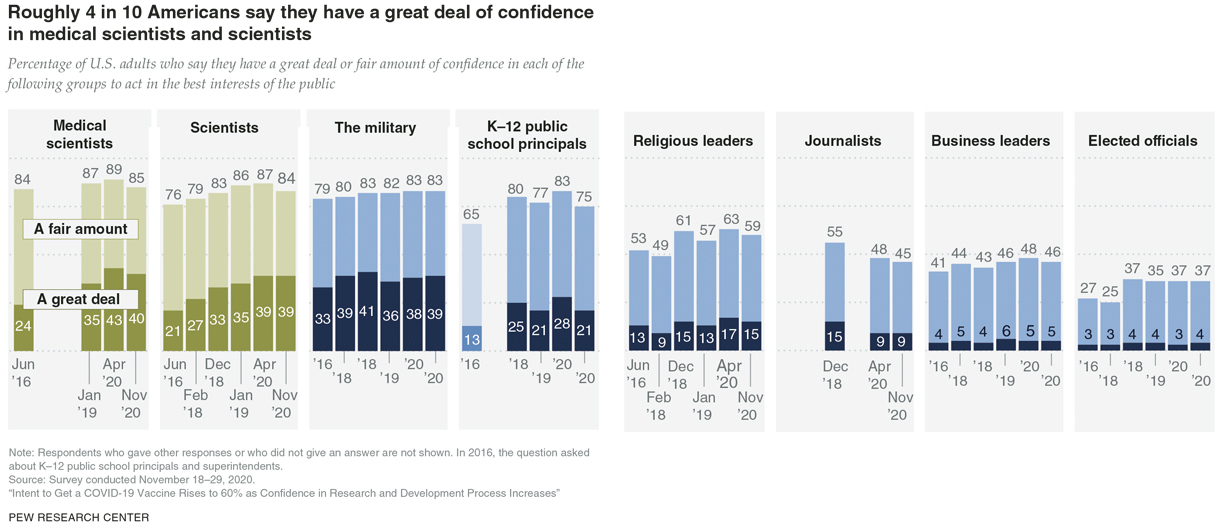

Our surveys—based on a nationally representative sample of more than 10,000 respondents—found that public confidence in scientists to act in the best interests of the public has been ticking upward since before the COVID-19 pandemic. As of November 2020, 39 percent of Americans reported a “great deal” of confidence in scientists to act in the public interest, up from 35 percent in January 2019, before the outbreak. Another 45 percent of Americans held a soft positive position, saying they had a “fair amount” of confidence in scientists. Just 15 percent said they had not too much or no confidence at all in scientists to act in the public interest.

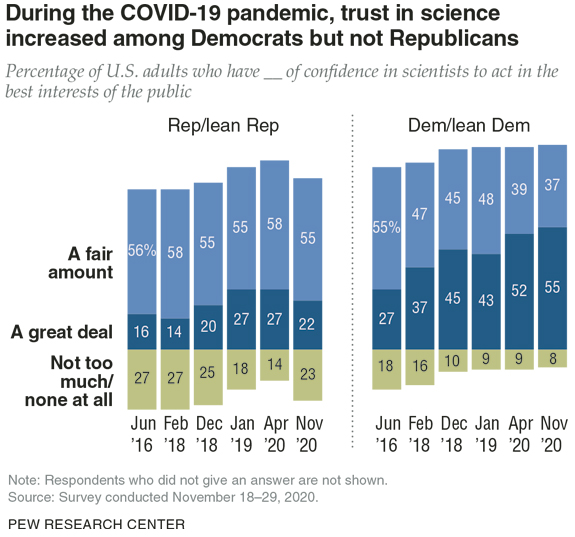

The modest rise in public trust in scientists stands out from reported public trust for other groups and institutions: Trust in the military held steady over the same period, and trust in journalists dipped further down. But the uptick in trust in scientists has been uneven among political groups. Trust in scientists has increased among Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party, but not among their Republican counterparts. Among Democrats, 55 percent say they have a great deal of confidence in scientists, compared with 22 percent of Republicans, a partisan gap that has roughly doubled since January of 2019.

Increasingly politicized public attitudes toward scientists can have important consequences. After all, one of the reasons for the ongoing interest in public trust in scientists stems from the idea that trust can be a harbinger of public views and behaviors regarding issues that are connected with science. For example, the willingness of Americans to get a coronavirus vaccine rose and fell with levels of public confidence in the vaccine research and development process as it was unfolding. As of February 2021, people who expressed higher trust in the vaccine-development process were 75 percentage points more likely to say they would get, or had already gotten, a coronavirus vaccine than those with low trust.

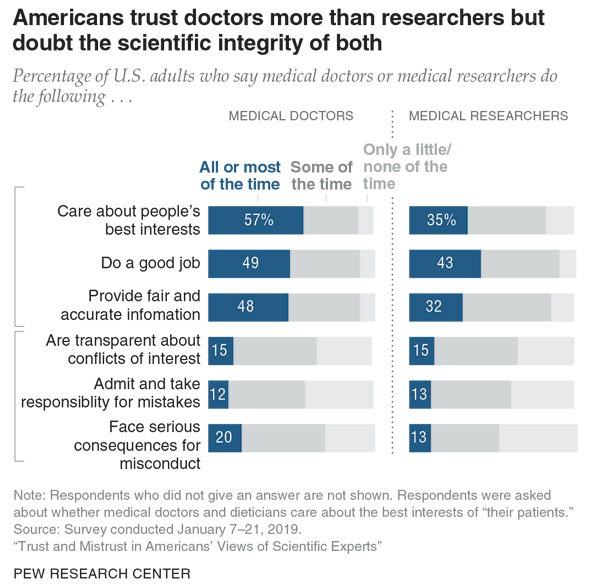

Center surveys have also documented that public trust in science is multi-faceted; public sentiment about scientists across those dimensions varies. Public judgments about scientists’ competence to do their job, for instance, can be quite distinct from views about scientists’ empathy for ordinary people or views of the accuracy of the information they provide. A Center analysis in 2019 highlighted the multiple dimensions of public attitudes: We found that trust in medical doctors was stronger than trust for medical research scientists, particularly around judgments of caring and concern. But there was a shared skepticism toward both doctors and medical researchers when it came to assessments of their scientific integrity.

Just 15 percent of Americans said either group was transparent “all or most of the time” about potential conflicts of interest due to industry ties. Similarly, small shares of the public thought medical doctors or research scientists would admit mistakes they made and take responsibility for such mistakes all or most of the time. Should professional or research misconduct occur, no more than 2 in 10 survey respondents believed that medical professionals would typically face serious consequences for their misdeeds.

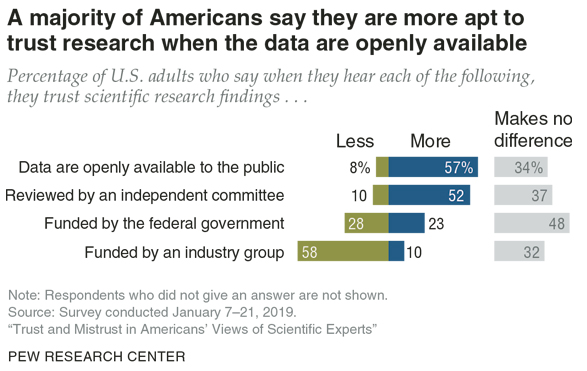

These findings indicate that public attitudes toward science are complex and nuanced. Survey data suggest that Americans are generally cautious or suspicious around issues of ethics and scientific integrity in medical research. We have found similar levels of skepticism toward scientists working in environmental and nutrition science. At the same time, the survey results hint at ways to build trust. Certain practices inspire greater confidence in scientists’ work. For instance, 57 percent of Americans said that they have more confidence in research findings when data are openly available to the public. And roughly half of Americans say that knowing there has been an independent or third-party review of findings increases their trust in scientific research.

An encouraging sign is that overall trust in scientists starts from a high baseline. In the most recent Center survey, 84 percent of Americans expressed a fair amount or a great deal of trust in scientists—significantly higher than the numbers for business leaders, and more than twice that for elected officials.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.