This Article From Issue

July-August 2003

Volume 91, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/2003.26.0

The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World. Jenny Uglow. xx + 588 pp. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. $30.

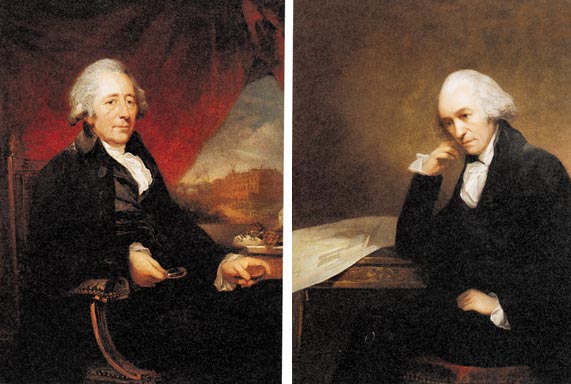

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was, as Jenny Uglow tells us, a club in an age of clubs. It derived its name from the members' custom of meeting on the Monday nearest a full moon, so that they could see their way home safely by moonlight. It was a small club, but a very influential one—indeed, a powerful one in the politics and the business of science and industry in 18th-century England. The members of the Lunar Society, whom I shall call Lunatics for short, were for the most part revolutionaries in one or another of the categories of science, industry, religion and politics. In the last two of those categories they were often of very different minds, but they managed to keep their meetings free from religious and political strife and rancor, and to concentrate on exchanging ideas about science, nature and industry. There were seven peripheral members clustered around a central group of five men: Charles Darwin's grandfather Erasmus, physician, poetical botanist and inventor; Josiah Wedgwood, potter extraordinaire; Joseph Priestley, the voice of Dissent, political radical and chemical conservative; James Watt, inventor of a much-improved steam engine; and Watt's partner Matthew Boulton, a manufacturer of steam engines and much besides, who told James Boswell, "I sell here, Sir, what all the world desires to have—Power."

From The Lunar Men

These five, along with the lesser Lunatics, were, Uglow tells us, "at the leading edge of almost every movement of its time in science, in industry and in the arts, even in agriculture." This book portrays them and their families, their entrepreneurial energy, their industrial acumen, their scientific debates and rivalries, and their financial and romantic involvements.

Uglow shows these men in their time, over a period that stretches from the American Revolution and the global war that ensued to the aftermath of the French Revolution, when to be a democratic radical like Priestley was physically dangerous. The Birmingham rioters who destroyed Priestley's house, laboratory, papers and meeting house, or chapel, on the second anniversary of Bastille Day were incensed enough to have turned into a lynch mob, had they encountered him during their rampage. Uglow's account of those "King and Country" riots is the most vivid I have seen. Wedgwood, like Darwin, became vigorously engaged in the campaign against the slave trade, even as he lobbied and maneuvered to maximize his profits and restrain the competition. Industrial espionage is a recurrent theme—how to secure patents, protect intellectual property and, where possible, steal industrial secrets from others; Boulton and Watt are much-concerned participants in that theater.

The Industrial Revolution was about power and money as much as it was about machines and science. Birmingham became a major industrial city in large part thanks to the efforts of the Lunatics. Uglow recognizes Vulcan with his forges as the patron of Birmingham but notes perceptively that the city was as much a center of Enlightenment as was Edinburgh or Bordeaux. The Lunatics were prominent in the financing and politics of canals and railroads, and Uglow writes vividly about canal fever. Boulton and Watt were skilled participants in mining industries, especially in Cornwall, where tin and copper mining imposed heavy demands on the workforce and on the pumps that made it possible to mine even under the sea.

Uglow asserts that her book "smells of sweat and chemicals and oil, and resounds to the thud of pistons, the tick of clocks, the clinking of cash, the blasts of furnaces and the wheeze and snort of engines but it also speaks of bodies, courtships, children, paintings and poetry"—and so it does. Through her collective biography of the Lunatics, she offers many insights into the history of England during the early Industrial Revolution. She builds her portrait through many vignettes: Wedgwood's stoical acceptance of the amputation of a leg, and his invention of a pyrometer; Darwin's flirtations and grief; Watt's invention not only of steam engines but also of a wholly impracticable device for copying statues; Priestley's absorption in chemical research using kitchen vessels as well as apparatus that was purpose-built for him by Wedgwood and then used as the model for commercial sales; Boulton's combination of paternal care of his workforce with the absolutism of a merchant prince. This book, like the group of men at its center, offers a rich and improbable bill of fare.

Women feature prominently: We meet Emma Wedgwood, who married her cousin Charles Darwin; Elizabeth Pole, who married Erasmus Darwin; several Edgeworths (Richard Lovell Edgeworth, a latecomer to the Lunar Society, had four wives in succession, and numerous offspring, including the novelist Maria and Anna, who married the fat, democratic Dr. Thomas Beddoes); Mary Wilkinson (the daughter of an ironmaster), who married Joseph Priestley; the Priestleys' daughter Sarah; Mary Robinson and her sister Anne, successive wives to Boulton; and many others. Generally speaking, their minds were treated with respect by their spouses and fathers, but they were not expected to apply their learning; raising children was their principal employment.

Uglow is careful about the science and tells us a good deal about mineralogy and geology, chemistry, and Linnaean botany, whose sexual imagery was so delicious for Erasmus Darwin in his book Loves of the Plants. She shows the Lunatics gain acceptance as men of science: Five of them were elected to the Royal Society of London in one year. She explains clearly and deftly improvements to the steam engine, the science of latent heat that underlay it and the importance of the separate condenser. She deliberately uses modern terms: science and physics instead of natural philosophy, sulphuric acid instead of vitriol, scientist instead of natural philosopher. But because she flags this for the reader, the anachronisms are at least blunted, and her story is accordingly accessible to a wide readership.

Uglow clearly portrays the extensive foreign networks that, for instance, linked Priestley to Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. She has made very good use of wide-ranging primary sources and less use of the secondary sources dealing with the chemical and industrial revolutions. Her emphasis on the documentary record gives the narrative real vitality; it is free from the jargon and theoretical debates that sometimes obscure the subjects they purport to illuminate.

This book is a treasure trove and a pleasure to read. It deserves a wide audience. Although we already know a great deal about individual members of the Lunar Society, there will be few who finish the book without finding much that is new, and nearly all will come away with an enhanced understanding of science and technology in the Industrial Revolution.—Trevor H. Levere, Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, University of Toronto

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.