This Article From Issue

July-August 2006

Volume 94, Number 4

Page 365

DOI: 10.1511/2006.60.365

Coming to Life: How Genes Drive Development. Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard. xiv + 166 pp. Kales Press, 2006. $29.95.

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard is one of the pioneers in the groundbreaking discoveries that revealed how genes regulate the development of animal embryos. For this effort she shared the 1995 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Eric F. Wieschaus and Edward B. Lewis. In Coming to Life, she provides an engaging and clear summary of what developmental biologists now understand about how embryos work.

The existence of such an apparently simple guide shows how much we have come to take for granted the explanation of development by gene regulation. However, it should be understood that what Nüsslein-Volhard describes actually represents the outcome of one of the premier intellectual triumphs of human thought—one that has been achieved within only the past two and a half decades.

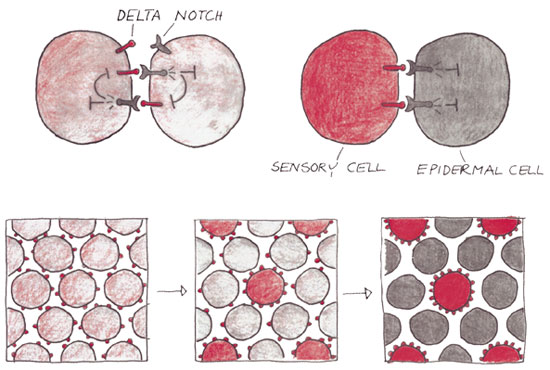

From Coming to Life.

Consider the profound difficulty embryonic development presents to an observer. A complex organism, such as a chick, frog, insect or human, arises in an orderly and magical way from an apparently structureless egg. When embryology was in its infancy in the 17th and 18th centuries, the thought was that no animal could arise from such nothingness. Thus was born the theory of the homunculus: the idea that an infinite set of tiny individuals were contained, one within another, in each egg—or in each sperm (there was vigorous disagreement as to which). Development was seen as the visible unfolding of a preexisting individual. Unhappily for this wonderful notion, in the late 18th century Caspar Friedrich Wolff showed by microscopy that embryos contained cells but no homunculus—there was no preformed entity.

So, whence comes the information needed to build an individual from scratch? The rediscovery of Mendelian genetics early in the 20th century suggested that genes provided the instructions, but the theoretical foundations of how genes worked were still lacking, and any demonstration that genes were crucial to development was slow to come. With the work of François Jacob and Jacques Monod on gene expression and regulation, the stage was set in the mid-1960s to understand development in terms of the role of information copied from DNA to messenger RNA and then used to construct proteins. By the 1980s developmental genetics was beginning, and the first major organism to draw its attention was the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, which had already been for some time the primary species for the study of genetics.

The subtitle of Nüsslein-Volhard's book is How Genes Drive Development. That's really the essence of her conception of developmental biology, a view that guides the organization of the book. She begins with chapters that introduce the genetic machinery, heredity, chromosomes, genes and proteins. She moves on to a brief discussion of the role of model organisms that have been crucial in developmental genetics and proceeds to the first of these, D. melanogaster.

The development of Drosophila is indeed at the heart of her story: She elegantly and plainly describes the search for genes that regulate development and lays out the mechanisms by which their expression generates patterns in the growing embryo, explaining along the way how the proteins those genes encode interact with other genes. Here's how it works: First, broad patterns are produced, followed by ever more precise ones that block out the body plan of a fly and the identities of its parts. Nüsslein-Volhard's research has elucidated much of this. Hence she can describe these goings-on authoritatively.

From there she explains general principles by which the overall form of the organism arises. At work are various activities and interactions among cells—interactions involving gradients of certain molecules; the movement of signals generated by one cell to influence its neighbors; growth; division; the maintenance of stem cells; and specific patterns of programmed cell death. Nüsslein-Volhard describes complex topics clearly, making an invisible world visible to the reader.

The second developmental model system that Nüsslein-Volhard presents is the zebrafish, which she uses to illustrate some of the crucial developmental features of vertebrates. She was a leading pioneer in building the developmental genetic study of these organisms, just as she had been with the fruit fly—although unfortunately in neither case does she discuss her own vital roles with these developmental genetic systems.

Nüsslein-Volhard gives a nice but all-too-brief treatment of the development of mammals and how it is studied. She uses this outline to introduce major aspects of human development that we indeed should all know about. She also discusses some aspects of evolution in very broad strokes, usefully demystifying how animal body plans arose. The most interesting chapter, apart from the primary ones on developmental genetics, is the final one, on current topics. There she gives a clear-eyed perspective on topics generally clouded by contentious and not necessarily well-informed debate: human cloning, in vitro fertilization, embryo research and stem cells. Her discussion incorporates a sensitivity to the complexity of ethical and legal issues.

As with any book that attempts a concise generalization of a complex science, there are a few mistakes, mainly on historical points. Thus when Nüsslein-Volhard suggests that before Darwin, embryonic resemblances were thought to show "a lack of creativity on the part of the Creator," she misses the point for 19th-century scientists, who took them to show the use of a common ground plan. Also, Ed Lewis did not discover Hox genes in the 1930s. These genes were first detected by others, notably Richard Goldschmidt; Lewis later ascertained their roles and inferred their mode of evolution. The statement that humans did not descend from apes is incorrect: We descended from primitive apes, ancestral both to us and to living apes. These occasional errors do not affect the core information and arguments of the book.

Nüsslein-Volhard has given us a compact, vibrant, lucid guide to modern developmental biology. She makes the text informative and precise, and renders difficult concepts readily understandable. The book is illustrated with charming drawings by the author that effectively illuminate her points. This is a marvelous introductory resource to anyone wanting to understand what developmental biology is all about.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.