This Article From Issue

January-February 2007

Volume 95, Number 1

Page 85

DOI: 10.1511/2007.63.85

The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico. Joseph Masco. xvi + 425 pp. Princeton University Press, 2006. Cloth, $65; paper, $24.95.

Nuclear weapons have long invited paradox, being seen by some as instruments of genocide and by others as a foundation for enlightened peacemaking. Joseph Masco, a cultural anthropologist, entreats us to consider additional paradoxes in his fascinating new book, The Nuclear Borderlands. He asks how the massive American nuclear weapons industry could be so invisible today, even though it occupies more than 36,000 square miles (an area about the size of Indiana) and nearly $6 trillion was spent on it over its first 50 years. He likewise notes that the United States, while doggedly pursuing nuclear weapons in the name of national security, has had more nukes exploded on its territory than any other nation: The country conducted 1,149 test detonations between 1945 and 1992, 942 of them within the continental United States. The release of radioactive fallout during the era of above-ground testing alone (1945–1963), subsequent government studies have concluded, will result in at least 11,000 excess deaths from cancer in the United States.

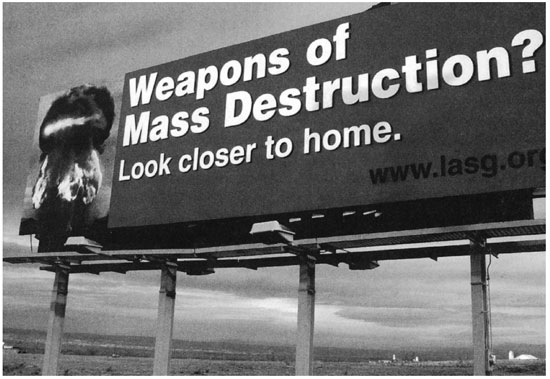

From The Nuclear Borderlands.

The book analyzes four distinct subcultures within the orbit of Los Alamos National Laboratory. First Masco describes the weapons scientists. Over time, he argues, the art and science of designing nuclear weapons have become separated from any visceral appreciation of their true destructive force. The scientists and engineers who built the earliest nuclear weapons and witnessed the original tests routinely talked about the frightening bodily reactions induced by the bomb: blinding flashes, searing heat, the force of the shock wave. Once testing went underground (following the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963), effects of the bombs were mediated through remote sensors. Weapons designers sat in permanent control rooms, eyes fixed on computer monitors. Since the cessation of testing in 1992, scientists and engineers have "experienced" the bomb only through computer simulations or small-scale, non-nuclear experiments. At the same time, Masco writes, the emphasis has turned more and more to perfecting "safe and reliable" bombs, deflecting attention from the fact that the devices are hyperdestructive military weapons.

Los Alamos sprang up during World War II in the midst of several Pueblo reservations, the second subculture Masco discusses. The end of the Cold War released simmering tensions between the various sovereign nations and the U.S. government. For nearly two decades the laboratory conducted implosion tests with radioactive lanthanum 140, secretly spewing dangerous fallout throughout Pueblo communities, contaminating water supplies and grazing lands. Laboratory protocol actually required that the tests be conducted only when prevailing winds would carry fallout over Indian lands, euphemistically referring to these regions as "uninhabited." Not surprisingly, since the mid-1990s many Indians in the region have vocally blamed the laboratory for elevated cancer rates among their populace.

Yet on the flip side, several Pueblo communities have accepted Los Alamos's invitation to store nuclear waste on their lands in exchange for large payments. As Masco explains, the recent waste-storage-for-profit initiatives emerged just as other groups renewed legal challenges in an attempt to curtail Indian casinos. Several Indian communities now see participation in the "plutonium economy" as a necessary step for economic survival.

Masco also analyzes the effect of Los Alamos on local Hispanic communities, pointing out that the areas around the laboratory are hugely diverse, both economically and racially. New Mexico is one of the poorest states in the nation, even as Los Alamos County boasts one of the country's highest median incomes. Many of the low-level employees at the laboratory—which is the biggest employer in the region—come from neighboring Hispanic communities, several of which pre-date American independence by more than a century. Some Nuevomexicanos see the lab as a necessary economic lifeline, providing the steady jobs with which to sustain their tiny-village way of life and its 400-year history. They worry that the end of the Cold War might lead to downsizing at the laboratory, upsetting their delicate economic balance. Others see the lab as a foreign colonizing force and accuse it of being out of touch with local traditions, usurping land that they say had been loaned to the federal government only for the duration of World War II, and leaving behind damage to public health and the environment that most likely can never be fully remediated.

Laboratory scientists, Indians and Nuevomexicanos live in uneasy tension with the fourth set of players Masco studied: the antinuclear and environmental activists based in nearby Santa Fe. Since the end of the Cold War, the predominantly white, middle-class protestors have hammered at the laboratory, often waging successful court battles over its medical and environmental responsibilities. Locals now rely on many of the Santa Fe groups for health and environmental information, which has proved difficult to glean from the laboratory directly. But they remain wary of anything that might destabilize the laboratory, because it remains so central to the local economy. Many Indians and Hispanics also bristle at some of the activists' patronizing lectures on "responsible" stewardship of their own land.

As Masco demonstrates, several events brought these tensions into the open. The allegations of espionage against Los Alamos scientist Wen Ho Lee, first aired publicly in 1999, fixed national attention on the lab, which appeared to be floundering, rudderless, now that the Cold War had ended. The affair also exacerbated concerns about racial profiling within the sprawling establishment. The Cerro Grande forest fire of 2000, meanwhile, which threatened several sensitive laboratory facilities, highlighted the fears of local residents about lingering environmental effects of a half-century of weapons development and the reservoirs of waste still stored at the laboratory. Plutonium 239, for example, which is highly poisonous to plants and animals even when not configured into a critical mass, has a half-life of more than 24,000 years. Other deadly by-products survive for centuries or millennia, far beyond the time-horizon of any realistic government storage program, or indeed of any particular government. The U.S. Department of Energy has already declared 109 distinct sites to be national "sacrifice zones," too contaminated by nuclear waste ever to be reclaimed.

Masco's important and impressive study ably demonstrates that nuclear weapons need not be detonated to have profound effects—effects that extend far beyond the well-studied realms of politics and international relations. The quest to build the bomb has reshaped the nation's infrastructure, economy and environment. It also continues to mold the daily lives and nightly fears of several communities still learning to live with each other in the shadow of Los Alamos.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.