This Article From Issue

September-October 2006

Volume 94, Number 5

Page 471

DOI: 10.1511/2006.61.471

Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra. John Derbyshire. viii + 374 pp. Joseph Henry Press, 2006. $27.95.

It is hard to know what to make of John Derbyshire's new book, Unknown Quantity. The subtitle suggests that it is a history of algebra, and developments are indeed presented in chronological order. However, it is really three books: a history of algebraic ideas, a set of "mathematical primers" explaining the ideas, and a lot of interesting stories about algebraists—many true, some embellished and some misleading. The book is at its best in explaining the mathematics of the period from 1590 to 1860—from the invention of general algebraic symbolism by François Viète, or Vieta, through groups of permutations and their application to the solution of polynomial equations, to the invention of vector spaces and fields. Reading those sections can teach somebody who doesn't know the algebra what the basic ideas are and something about the historical relationship among them.

Derbyshire is also the author of the well-received 2003 book Prime Obsession, a popularized account of the Riemann Hypothesis and some of the people who worked on it. But a caution is in order about his current book: Although Unknown Quantity claims to be a history, Derbyshire, when he hears a good story, sometimes prefers telling it to checking it.

Here are just two examples of the way he handles evidence: Derbyshire says that when Descartes chose the letter x to represent the principal unknown, he did so for the convenience of the printer, because x is less used in French than y or z. In fact, though, x is used more often than y in French, at least according to cryptography texts by Fletcher Pratt and Helen Fouché Gaines that I consulted. Derbyshire's source for his assertion is Classic Math, a book for high-school students, whose author, Art Johnson, gives no footnote for the claim but who may have misunderstood a conjecture made in 1905—almost 300 years after Descartes—by Gustav Eneström that appears in a book in Johnson's bibliography, Florian Cajori's History of Mathematical Notations. Eneström supposed that x was chosen because it occurs more often than y and z, and printers therefore would have had more x's on hand.

Also, Derbyshire repeats the canard that J. J. Sylvester might have been a homosexual, in part because—as if this constituted appropriate supporting evidence—Sylvester wrote poetry and "enjoyed singing in a high register" (Sylvester was indeed a tenor, and serious enough to have taken singing lessons from the French composer Charles Gounod).

In addition, on several occasions when Derbyshire doesn't seem to know much about some relevant historical development—say, the degree to which the ninth-century algebra of al-Khwarizmi goes beyond that of ancient Babylonia, or the meaning of the "geometrical algebra" of Book II of Euclid's Elements—he dismisses it with a putdown.

There is also considerable carelessness and indifference to detail. For instance, in Figure 15-1, the caption labels the title page on the left as belonging to the 1941 (first) edition of Garrett Birkhoff and Saunders MacLane's A Survey of Modern Algebra—despite the fact that the words "Revised Edition" appear clearly below the title. Contrary to a claim Derbyshire makes, Euclid was not the first to give the standard proof that the square root of 2 is irrational (apparently Derbyshire is unaware of Aristotle's earlier discussion in the Prior Analytics). Nor is Immanuel Kant the ultimate source of the distinction between analytic and synthetic methods in geometry (a claim that neglects Newton, for instance).

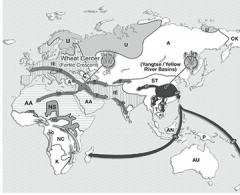

From Unknown Quantity.

The amount of space Derbyshire devotes to a historical topic or a mathematician seems to vary with how interesting he thinks it is, rather than how important it is; for instance, six full pages are devoted to the biography of Alexander Grothendieck (admittedly, he has led an interesting and colorful life), but only one sentence to the biography of Richard Dedekind. The endnotes are even more chatty and tongue-in-cheek than the text. There is no bibliography, although the assiduous reader can compile one from the endnotes, and it will be a mixture of the first-rate (Michael Artin's Algebra, Harold M. Edwards's Galois Theory, histories of algebra by Isabella Bashmakova and by B. L. van der Waerden, to name some examples) and the idiosyncratic (such as Rudy Rucker'sMathenauts and Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part I).

The mathematical primers Derbyshire provides in Unknown Quantity are generally valuable, but some are too elementary for a reader trained in science, whereas others are too difficult and too brief for nonalgebraists. Unfortunately, some important results whose proofs are accessible to a general reader, and which would clarify the exposition of algebraic ideas, are not proved here. For instance, Derbyshire states that the rational numbers are countable (not explaining how we know this) but that the real numbers are not; he does not even refer the reader to a proof elsewhere. Again, he asserts that the general cubic equation can be transformed into one with no x 2 term, but he does not justify the assertion by reviewing the binomial expansion for (a + b)3. When he covers more advanced material of the late 19th century and the 20th century, things come by too fast and are sometimes only mentioned and not explained; for example, although he gamely tries, he does not fully specify for a general reader how Galois theory addresses the solvability of polynomial equations. And someone ignorant of category theory will not be helped by the explanation here, although Derbyshire does have fun with the term "forgetful functor."

From Unknown Quantity.

Nonetheless, a reader who wants to learn some theory of equations and modern algebra in a relatively painless way will find this book attractive. The explanations of many algebraic topics are accessible and clear, especially those of the following: how Vieta's new general symbolic notation demonstrates the relations between roots and coefficients of polynomials; symmetric polynomials and solvability; the roots of unity; how Paolo Ruffini's proof of the unsolvability of the quintic worked; how studying permutations of roots of polynomial equations gave rise to group theory; how linear transformations and matrices are related; the nature of quaternions and octonions; what an invariant is; an introduction to algebraic geometry; what a vector space is; and what the differences are between groups, division rings and fields. Those explanations also make clear why mathematicians cared about these problems and how these concepts were used. The anecdotes, although not reliable, certainly make the book fun to read.

Still, a reader wanting to learn the history of algebra accurately while also learning the algebra in question would be better served by reading the sections on algebraic topics in Victor Katz's magisterial History of Mathematics: An Introduction (Addison-Wesley, second edition, 1998). Anyone seeking fascinating—and reliable—biographical material on past algebraists should start with the Dictionary of Scientific Biography (a source Derbyshire himself has used) and, for contemporary mathematicians, the highly readable interviews in Gerald L. Alexanderson and Donald J. Albers's Mathematical People and More Mathematical People.

But perhaps I'm being a little harsh about the contents of the book not being entirely dependable. After all, Derbyshire's subtitle, "a real and imaginary history of algebra," does give the reader fair warning.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.