This Article From Issue

March-April 2013

Volume 101, Number 2

Page 149

DOI: 10.1511/2013.101.149

VISIBLE EMPIRE: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. Daniela Bleichmar. xii + 286 p. University of Chicago Press, 2012. $55.

In an age when human activities are causing the natural world to decline rapidly, both in biodiversity and in sheer magnificence, it is fascinating to contemplate a time when exploration was, with similar rapidity, allowing members of the Western world greater comprehension of Earth’s beauties. The inexhaustible encyclopedic appetite of 18th-century Europe is revealed by the more than 12,000 illustrations of plants made throughout the Spanish empire—in the New World, the Philippines, and regions in the Americas and Asia touched by Spanish expeditions—during a period of approximately 25 years spanning the late 1770s and the early 1800s. In Visible Empire, Daniela Bleichmar curates a selection of these images, presenting them along with seven insightful essays on such entwined subjects as empire, race, botany and natural history. In concert, the essays and images offer insights into not only the botanical works themselves, but also the times, visions and dreams of the people of the era.

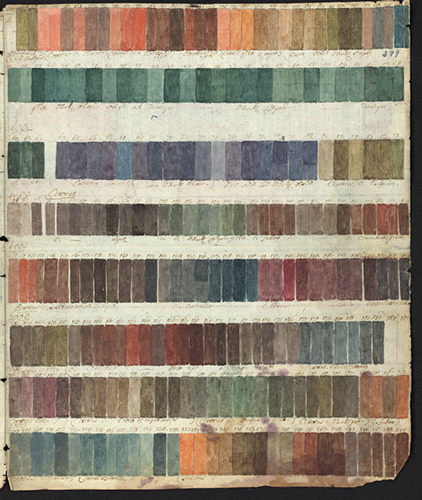

From Visible Empire.

The body of art that is Bleichmar’s subject is preserved in air-conditioned vaults at the Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid. The selections she includes represent the collection as unique in both the number and the excellence of the paintings it contains. Through her deep and fascinating analysis, we are transported back through the centuries and brought into contact with the motivations and attitudes of the Spanish explorers, scientists and artists who made the images. Spanish authorities saw the discovery and use of these new kinds of plants as a possible source of wealth. They also viewed the knowledge that they were able to exhibit as a competitive weapon in their ongoing struggle with other nations—and in the attempt to recast conceptions of the regions where the paintings were produced. Contemporary viewers, by contrast, might see the images primarily as an impressive body of artistic work, with little political or historical meaning, were it not for the existence of this thoughtful book.

The “discovery” by Westerners of the New World, Asia, Africa and, ultimately, Australia, and the subsequent exploration and colonization of these regions, led quickly to a strong desire on the part of imperial explorers to describe and catalog everything they could find. This impulse can be seen as part of the broader desire to catalog and rationalize knowledge that was exemplified by many of the intellectual activities of the 18th century. These efforts included the great work of the encyclopédistes in France; the comprehensive investigations of life made by Carl Linnaeus; and initiatives such as that represented by the body of work discussed in Visible Empire. The result was that richness much greater than had been recognized earlier began to unfold.

A central figure of the historical period analyzed in this book was José Celestino Mutis, who was born in Spain and lived in Santa Fe de Bogotá (now Bogotá, the capital of Colombia) for most of his long life. Mutis arrived in South America in 1761 at the age of 28, and was later ordained a priest. Realizing the opportunities afforded by his new residence, he proposed to the King of Spain a continuing botanical expedition. Royal permission led to 25 years of exploration, starting in 1783. Ranging deep into the interior of what is now Colombia via the valley of the Río Magdalena, Mutis and his associates discovered and described thousands of new kinds of plants, arranging for many of them to be illustrated. His story and those of many others are recounted in the course of Bleichmar’s essays.

Mutis was visited by Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland during the course of their expedition throughout Latin America (1799–1804)—a journey that revealed to the West the incredible biological riches of the tropics. Just a few years afterward, Napoleon’s invasion and occupation of Spain, coupled with the independence movement that subsequently swept its empire, brought to an end both the possibility of and the motivation for continuing efforts to catalogue the botany of lands occupied by the Spanish Empire. In part as a result of these events, some of the collection of plates now stored in Madrid was not published at the time. The delay in publication may also have resulted from the Spanish empire’s desire to properly exploit the information they contained; colonial powers sometimes displayed ambivalent feelings about publishing descriptions of the biological wealth of their overseas territories.

In a rich and scholarly fashion, Bleichmar brings us as close as humanly possible to understanding the era. We are afforded a sense of the Spanish government’s motivations in sponsoring the expeditions and residencies that led to the creation of these plates; the relationships between the explorers, botanists and artists responsible for the images; techniques for accurately rendering fragile specimens whose colors rapidly faded; and the way the images decontextualized botanical specimens from their native environments and from the people who lived there.

An estimated 100,000 or more plant species are native to Latin America—a quarter or more of the world total—and scientists still do not have a thorough understanding of this flora. Throughout the world, habitat destruction, incursions by invasive species, global climate change and other forces are driving species to extinction much more rapidly than we can find and recognize them. During the period described in this book, the world population reached one billion people for the first time; now it is seven billion, many more than the world can nurture sustainably. It would be a rational step, if the means and motivation could be found, for nations to collaboratively embark on an exploration of the world’s botany that is comparable in scope to that described so beautifully in Visible Empire. Without such an effort, much of the life that exists now will be lost forever, without ever having been seen by humans.

Peter H. Raven is George Engelmann Professor of Botany Emeritus at Washington University in St. Louis and President Emeritus of the Missouri Botanical Garden, which he headed and developed for 39 years. He is a co-founder of the Flora of China project, an effort to produce a descriptive encyclopedia of the 32,000 different kinds of vascular plants there. The project involves the collaboration of botanists from throughout the world; the last of 50 volumes will appear this year.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.