This Article From Issue

March-April 2015

Volume 103, Number 2

Page 152

DOI: 10.1511/2015.113.152

FEARLESS GENIUS: The Digital Revolution in Silicon Valley, 1985–2000. Doug Menuez. 192 pp. Atria, 2014. $39.99.

Another day, another urgent deadline. In a white stucco office park with perfunctory geometric green trim, the 26-year-old division president of our IT firm paused during a staff meeting. “It’s okay if you make mistakes,” he said. “They just have to be fast mistakes.” It was the first quarter of 2000. In one sentence, he had hit on what would become the year’s twin themes for our firm and, as it turned out, so many others: the relentlessness of the clock and the interdependence of innovation and failure.

Photographer Doug Menuez’s large-format book Fearless Genius takes the collapse of the dot-com bubble in 2000 as the end point of a 15-year project documenting Silicon Valley’s major players. Originally he wasn’t planning on a long-term gig. In 1985, Menuez, a seasoned photojournalist, was burned out from covering catastrophes such as the AIDS crisis and the 1983–1985 Ethiopian famine. Seeking a new subject—one he hoped would be more imbued with optimism—he looked toward Silicon Valley and reached out to Steve Jobs, recently ousted from Apple. Jobs was interested in documenting his latest venture, NeXT, an IT company focused on revolutionizing the education sector. Soon Menuez was in.

The project proved so riveting that Menuez began approaching leaders at other young tech companies including Adobe, Microsoft, Apple, Intel, and Sun Microsystems, requesting the same full, behind-the-scenes access. Learning of his work with NeXT, they agreed. The project became open ended, evolving as Menuez grew more familiar with his subjects and their work: “The objective role I originally sought as a photojournalist fell away and I began to embrace a more subjective, interpretive approach. I maintained distance but was no longer able to remain completely neutral.”

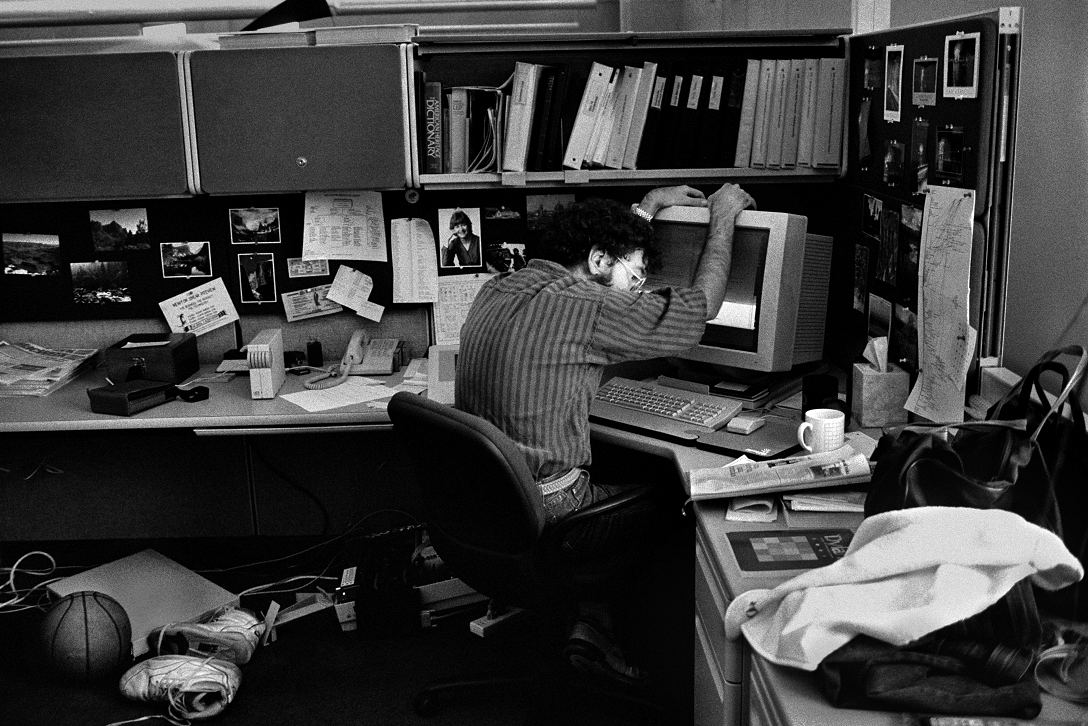

The resulting 250,000 images, now housed at Stanford University, document a burgeoning industry from an exceptionally intimate viewpoint. Fearless Genius distills this archival bounty to just under 200 pages of black-and-white photographs that capture distinguishing features of high-tech culture in the 1980s and 1990s: its landscape (hastily populated cubicles crisscrossed with makeshift wiring), population (magnetic innovators; disheveled, fatigued programmers; masked, clean-suited microchip fabricators; crisply attired publicists), and common emotional trajectories (pronounced pinnacles and valleys unified by numbingly hard work).

Photograph by Doug Menuez. From Fearless Genius, Atria, 2014.

Menuez has a sharp eye for habitat, and he made a point of turning his lens to subtle everyday details of the high-tech environment: “Having studied visual anthropology, I knew that this was data that others might later decode to draw conclusions about this new culture that had come to fascinate me.” In the process he captured now-familiar signifiers of a new kind of workplace. A worker photographed at Adobe in 1988 wears headphones as she stares at her computer screen; behind her, an almost poetic note at the entrance of her cubicle states, “Trying To Think / tough task thinking / Please do not disturb.” On another page, a whiteboard displays a hastily scrawled to-do list—in this case one written in 1987 by Steve Jobs that includes the categories “Deep Shit” and “Ankle Deep Shit.”

Menuez’s respect for his subjects and their work lends humanity throughout the collection; his thoughtful captions add crucial perspective. The wide-eyed panic of an Apple marketing executive becomes evocative when we learn that she has just discovered, moments before a demo, that all the Newton prototypes are dead. In the context of Menuez’s detailed descriptions of tense product development timelines, moments of exuberant play seem all the more vital, as engineers skydive, coworkers dress in costumes, and work teams celebrate water-gun combat victories.

Packed with transfixing photos and framed by Menuez’s compassionate perspective, Fearless Genius conveys the ephemeral quality of the digital revolution while recognizing its enduring legacy. For all involved, some level of failure was inevitable, whether it arrived as a missed deadline, a lackluster demo, or a company bankruptcy. One of the book’s key virtues is allowing readers to witness these ups and downs for themselves. As Menuez notes, “Failure was as much a part of the process as the staggering success that is more commonly associated with Silicon Valley.”

Dianne Timblin is book review editor for American Scientist and author of the poetry chapbook A History of Fire (Three Count Pour, 2013). Find her on Twitter: @diannetimblin.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.