This Article From Issue

March-April 1998

Volume 86, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/1998.21.0

The Nature of Horses: Exploring Equine Evolution, Intelligence, and Behavior. Stephen Budiansky. 290 pp. The Free Press, 1997. (See Simon & Schuster) $30.

Books that present a popular overview of our scientific knowledge about horses are not new. The best known is probably paleontologist and evolutionary biologist George Gaylord Simpson's 1951 title Horses: The Story of the Horse Family in the Modern World and through Sixty Million Years of History (Oxford University Press). It was an excellent review of the field at the time, but of course is now rather outdated. More recently, the paleobiologist Bruce MacFadden produced a larger and more ambitious volume called Fossil Horses: Systematics, Paleobiology, and Evolution of the Family Equidae (Cambridge University Press, 1992) that not only covers aspects of equine science and evolution but also uses horses as case studies of various evolutionary concepts and theories. This new book by Stephen Budiansky, a former editor of Nature, is more like Simpson's in that its primary focus is on the horse itself. On the other hand Budiansky's book differs profoundly from those of either Simpson or MacFadden in that Budiansky really loves horses as animals, and it shows in every aspect of his book.

From The Nature of Horses.

This is not to imply that Simpson or MacFadden disliked horses in any way: In fact, in their writings they both obviously show great appreciation for the horse as a complex organism and for its ability to illustrate aspects of science and evolutionary history. But neither was, or is, an avid horseman, and neither appears to really be in awe of the horse as a magnificent beast. Budiansky's love for and appreciation of horses shows throughout this book, not just in the introduction where he admits to his own personal involvement with horses. His attitude towards horses is also apparent in the dust jacket. An obvious clue is the picture of the author on the inside back flap, taken with his palomino thoroughbred/quarter horse cross who takes him hunting in Virginia. But a more subtle clue, and a more telling one to me, is the illustration on the front cover, a reproduction of "Hunters in a paddock, and a town beyond" by Henry Calvert.

Calvert's 19th-century painting is of about the same date as the much-better-known animal artist George Stubbs, and therefore might seem to be a strange choice. Calvert's horses are not as artistically aesthetic nor as technically correct as the ones by Stubbs: As with many 19th-century paintings of horses, the heads and necks appear to be too small for the bodies. But these horses differ from those portrayed by Stubbs in a fashion that is perhaps more important. Stubbs's horses are always impersonal—beautifully drawn beasts that lack individual personalities. In contrast, Calvert's two horses are clearly known to the artist as personal friends. They are eyeing him as if they suspect that he is hiding treats behind the easel.

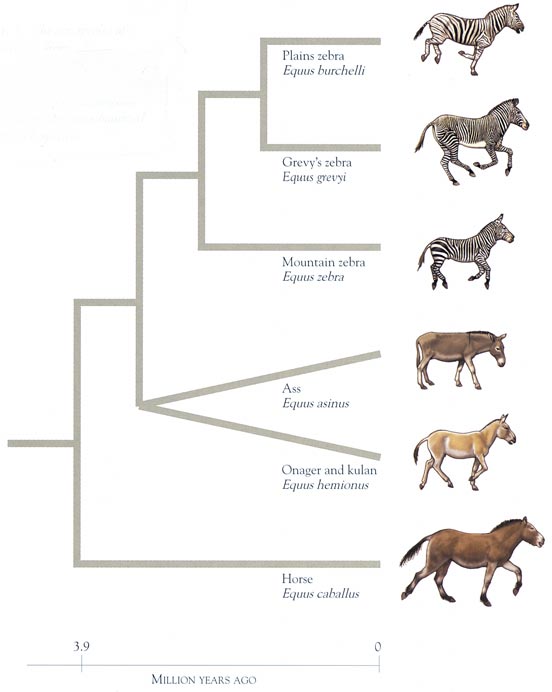

Budiansky's book commences in a rather traditional way, with an initial chapter on evolution. But rather than emphasize the standard story of horse evolution (the Eohippus-to-Equus success story), he covers some modern ideas on horse evolution and evolutionary theory in general. He includes the "bushlike" nature of the evolutionary radiation and the diversity of evolutionary trends, the ecological and functional consequences of increase in body size, the importance of climatic change and the role of contingency in evolution. (MacFadden covered much the same ground.) In the second chapter he emphasizes the likelihood of the extinction of the horse in Recent times, if it had not been for the fortunate accident of human domestication. This coverage of the new data and interpretations of the well-known story of horse evolution is an exceedingly useful summary, especially in the light of the continued out-of-date representation of the example of horse evolution in both equestrian magazines and creationist literature.

Several chapters cover aspects of horse behavior and socioecology. There is discussion of the history of the horse as an instrument of battle, bonding and social behavior among wild equids and domestic horses (including some entertaining personal anecdotes), equine perception (where he thoroughly debunks the continually repeated old myths that horses focus via a "ramped retina" and lack color vision entirely), and communication. I was delighted to see that the chapter on equid psychology mentions the work of Moyra Williams, my favorite author of semipopular horse books since childhood, but was sorry to see that her book is not cited in the bibliography.

I was especially intrigued by the suggestion that play in domestic adult horses, which suggests arrested development, may be an important element in the horse's willingness to engage in human sports and activities. (Anyone who thinks that horses don't play has never been in close association with them. My husband certainly didn't believe this until my mare repeatedly made off with his hammer as he was fixing the fence.) Certainly the proportions of domestic horses, which have longer legs and more tapered muzzles than the adults of wild equids such as Przewalski's horse, suggest retention of juvenile features (neotony). This hypothesis explains why zebras, which share a similar social system with horses, are not easily tamed. Although it is obviously necessary to have a social system where close personal bonds between individuals are transferable to humans, it's clearly not sufficient. There must also be a span of time of human and equid association for the selection of more juvenile, tractable behavior.

Later chapters deal with biomechanics, locomotion and metabolism. The coverage of locomotion begins with the history of the photographs of Eadweard Muybridge, continues through the theoretical work on animal gaits by Milton Hildebrand, and goes on to the studies of the energetics of locomotion by Richard Taylor and his associates. This again is an excellent summary of the field, although I am disappointed to see that the work of Elise Renders on Hipparion footprints, which shows that the "running walk" gait is probably a natural one rather than manmade, is neither emphasized again in this section nor cited in the bibliography. A final chapter on "Nature or Nurture" covers genetics, and includes some excellent diagrams of patterns of color inheritance as well as a discussion of performance breeding.

In summary, this book presents excellent coverage of the recent scientific discoveries and ideas that concern horses, written for both the layperson and the scientist. The author's personal interest in and involvement with horses greatly strengthens the presentation and coverage. My only complaint is that a more extensive bibliography would have made this book a better academic resource. This would be a wonderful book to use for an undergraduate seminar: The popular nature of the subject would be a great lead-in for a rigorous approach to many aspects of biological science.—Christine Janis, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Brown University

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.