This Article From Issue

November-December 2013

Volume 101, Number 6

Page 472

DOI: 10.1511/2013.105.472

THE BOOK OF BARELY IMAGINED BEINGS: A 21st Century Bestiary. Caspar Henderson. xix + 427 pp. The University of Chicago Press, 2013. $29.00 cloth, $18.00 e-book.

Caspar Henderson experienced his epiphany while reading Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges’s The Book of Imaginary Beings, which maps a fantastical array of creatures that have haunted humans’ mythic landscape through time and across cultures. “I was riveted—until I dozed off in the sunshine,” Henderson writes. “I woke with the thought that many real animals are stranger than imaginary ones, and it is our knowledge and understanding that are too cramped and fragmentary to accommodate them: we have barely imagined them.”

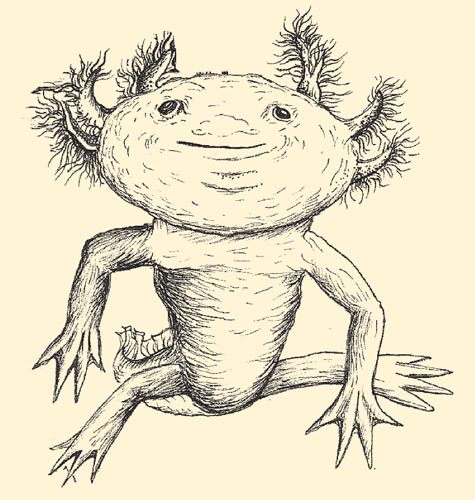

Golbanou Moghaddas

In response, Henderson has crafted a magnificent meditation on the complicated relationship between humans and beasts, The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: A 21st Century Bestiary. As a specimen of the medieval bestiary, a genre that blended real animals with imaginary ones, this text deconstructs by drawing on modern scientific detail, Eastern contemplative traditions, and Western pop culture.

A medieval bestiary makes for a phantasmagorical muddle of Latin mistranslation, Christian allegory, and unverified nature observations, studded throughout with literary adornments. Similarly, Henderson’s narrative ranges widely, beyond scientific detail, contriving along the way his own postmodern belles lettres. As philosophically far out as these meditations venture, however, each chapter holds fast to the scientifically real and radically “other” as both point of departure and final emphasis.

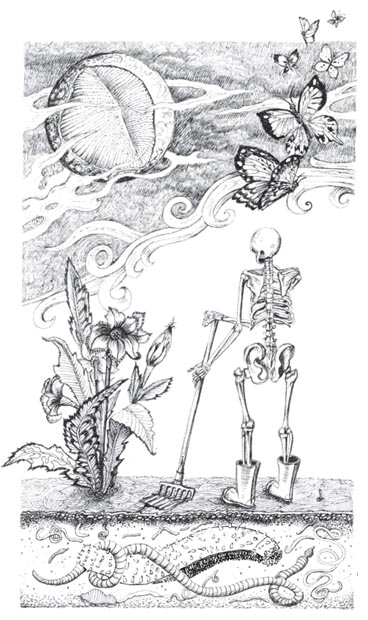

Golbanou Moghaddas

By repeatedly redirecting all manner of humanistic contemplation back to the beast under scrutiny, Henderson illuminates humanity’s moral imperative: to cultivate some long-overdue humility. For him, only a brave new interlocution between humans and the beasts they regard as alien will sufficiently expand human consciousness. At its most ambitious, his project is not only to raise our awareness of ecological threats to biodiversity but also to liberate us from a claustrophobic awareness of our own mortality and free us of our delusional human ego.

Structurally, traditional bestiaries herd their occupants into a familiar encyclopedic schema. Henderson adopts an alphabetical approach, moving chapter by chapter from Axolotl to Zebra Fish. Opening with the sublime or grotesque—but in any case scientific—details of one chosen animal, each chapter’s narrative circles back on itself in ever-widening arcs alternating between biological and humanistic contemplation, picking up and weaving in a colorful array of relevant threads, from monster movies to the myth of Orpheus to Zen insights. In the medieval texts, such roundabout narratives are largely an accident of unrestrained anthropomorphic appropriation. Henderson masterfully adopts that structure to unmoor humans’ tendency to appropriate.

In one chapter, Henderson confronts the reader with the anatomy and physiology of the eel, leaning into juxtapositions that the reader reflexively recoils from. “An eel’s eyes, bulging and unblinking, look like those of a corpse, and the way the animal moves its body—gracefully, without limbs or prominent fins—is disturbingly sensual,” he writes. A page later, he delineates the structure and function of moray eels’ second set of jaws, which lie deep in the back of their throats and then rapidly fire out of the first jaws to clamp down on distant prey. Rather than being repulsed, Henderson celebrates “this extraordinary ability to ‘vomit’ up a second set of fearsome teeth.”

Grounded first in abundant scientific detail, the eel chapter goes on to compare the similarly appointed creature from the 1979 film Alien, remarking how people fear monsters precisely because monsters incorporate something human into their ghastly, indomitable forms. Henderson considers humans’ fear of contamination central, citing cultural histories of war, pollution, mutation, and parasitism. This chain of association reaches its apex when he returns to the science of eels. “Stories that locate the monstrous as close to human beings as the jugular vein,” he writes, “let other animals off the hook.” By finally nailing his theme to scientific detail, he makes the case that the moralizing human histories he has just indulged “reduce the obstacles to seeing non-human animals for what they are and not as metaphors for something else.”

Paradoxically, Barely Imagined Beings repeatedly challenges the reader to stand down and be awed by that raw earthly otherness in which even the human consciousness, thereby humbled, may be embedded rather than set apart as a subject distinct from its objects. To that end, Henderson treats humans as just another weird beast, marked at no point of special ascendency by the chapter beginning with the letter H. His analysis of the human animal starts not with our remarkable self-awareness and consciousness but with bipedalism, because upright endurance running enabled humans to fashion hunting spears, which required big brains. “Man thrived, and learned to think, because (he) was born to run,” writes Henderson. Similarly, he traces the emergence of language to music, and music to the primordial surround-sound of songbirds chirping and flint being rhythmically chipped into tools.

Much as he stands back dispassionately from his fellow humans, Henderson reports unflinchingly on even the most grotesque physical details of the bestial world. Hagfish, for example, are “particularly fond of burrowing up the anuses of dead animals which they then devour from the inside.” The author’s directness in articulating the sublime is no less breathtaking. He relates with neither hesitation nor overreach the transport he experienced at age 17 while hiking in Norway:

I came to a grove of birch trees on a promontory above the water. The trees seemed tall after a season further north where little grows higher than your knee; big enough, at any rate, to look up into. And as I did so the sun broke through the clouds. Brilliant light burst across the lake and lapped on their bark and leaves in flakes and dapples of gold.

For Henderson, both the grotesque and the sublime present opportunities to notice what Buddhists call the “dependent arising” or “interbeing” of all phenomena. Readers spanning the humanities and the sciences will treasure this luminous reimagining of the real. The “barely imagined beings” Henderson refers to in his title seem, in the end, to be not so much scarcely imagined beings as beings successfully laid bare, revealed.

Jenny Jennings Foerst is an associate editor of American Scientist, and received an M.A. in English and a Ph.D. in American Literature from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.