How Can Art Move Us Beyond Eco-Despair?

By Robert Chianese

Grim news about climate change easily triggers a sense of helplessness. Art can help redirect that feeling into one of active engagement.

Grim news about climate change easily triggers a sense of helplessness. Art can help redirect that feeling into one of active engagement.

DOI: 10.1511/2015.114.176

The May 2014 National Climate Assessment, a report by more than 300 scientists, lays out climate change effects for the United States in a dozen broad categories. Rising temperatures, ocean acidification, dwindling biodiversity—the predictions are sadly familiar by now, and yet our adaptations to these conditions seem tentative and wary. Few coastal cities are pulling up stakes; regulatory responses, such as California’s new restrictions on the unchecked pumping of water to counter the region’s extraordinary drought, will take many years to implement.

From “Environmental Impact,” traveling exhibition, September 2013 to January 2016. Courtesy of David J. Wagner.

Many Americans seem willing to wait out what they believe to be temporary aberrations in climate, despite all the evidence to the contrary. Already on the West Coast we are starting to see flare-ups of class contention over water, the present-day equivalent of California’s gold. The sense of an imminent crisis is inescapable: Something is likely to crack.

Something already has—our psyches. A June 2014 study by social scientists charts the ill effects of climate change on people’s emotional states. Beyond Storms and Droughts: the Psychological Impacts of Climate Change, a 50-page report by the American Psychological Association (APA), gauges human reactions to environmental disturbance and catastrophe. At the community level, it finds climate change causing a loss of social cohesion, as well as increased violence, crime, social instability, aggression, and domestic violence. This bleak catalogue of ills mainly afflicts people whose communities have been devastated by climate change–induced fire or flood or hurricane, even more so for the poor and alienated. Feeling beset upon and hopeless, their very identity and autonomy become threatened, with manifestations of post-traumatic stress syndrome. Our planetary disturbance infiltrates our inner lives, with alarming and often unacknowledged effects.

These social ills have been with us for a long time. But today, for those of us who are fully aware of—who are dreading—the seemingly inevitable unfolding of climate change, the consequences may be even more personal and interior. The APA report refers to this condition as “ecoanxiety“ and cites a trio of disastrous symptoms: helplessness, fatalism, and resignation. This is what a lot of us feel. We may not put a name to it, but a sure sign of ecoanxiety is the humorless tone of environmental discourse. I would label this state as eco-depression, or more dramatically, eco-despair. I suspect anyone paying close attention to ecological effects feels it.

Eco-despair presents an interesting challenge. We want to remain engaged in actions that work to understand and communicate, as well as to reverse or slow climate change—but taking action requires excitement, and often a sense of mission. Keeping up protracted, often fractious connections to others can drain a lot of energy. Depression of any sort can sap motivation and leave one isolated with a triumvirate of mental pains: that “helplessness, fatalism, and resignation” that can leave one overwhelmed, bitter, and cynical. How might we treat eco-depression?

Art can help here—specifically, a certain kind of art that deliberately depicts and imaginatively confronts us with climate change.

Two exhibits with that very focus and the exact same title–Environmental Impact— bring home to us the effects of climate damage. David Wagner’s large, multiyear traveling show has 75 works by over 30 artists, whereas a short-term exhibit at the Weisman Museum in Malibu, California, has half as many works, all selected from the Weisman Art Foundation.

Part documentation, part meditation and reverie, and part creative expression, works in these exhibits jump out of the current cultural matrix as if called by our age of ecological catastrophe. This art wants us to witness what’s happening climate-wise, but mainly through the hand and eye and imagination of the artist.

Artist Chris Doyle creates a light box entitled History of the Twentieth Century I, illuminating the discarded, unrecycled junk of our “Waste Generation.” Old televisions dominate, with abandoned, obsolete factories and oil rigs in the background, and appliances to one side. On first look, the colorful jumble has a fantasy, theme-park aspect; the blue skies and boundless clean gear intrigue us. Yet, what sort of history have we here? What about this arrangement?

It seems a history of technology, or rather yesterday’s technology, before we began tossing out computers, displays, printers, tablets, and phones in ever-increasing numbers. Who does this? Most of us, certainly scientists, environmentalists, academics, publishers, students, climate-change worriers—and artists. Our Waste Generation’s 20th- century history, powerfully illumined by Doyle, includes us most painfully even in the absence of our particular junk.

As we condemn smoke stack industries, lament cars and oil, and scorn empty, frivolous television entertainments, we need to remind ourselves that we are major buyers and discarders of electronic devices. Even our recycled e-waste may just get dumped in a landfill in China or Ghana or be dismantled for materials by the poorest of people. This awareness connects us to both the world’s wasters and wanters, humanizes us and the problems we face, together. De te fabula: “The tale is about you.”

This could lead to guilty despair—our junk eats up enormous resources and carbon-based energy. Or, it might lead to revised policies that work to ensure recycling, or to devising e-products easy to dismantle, or simply to holding on to our gear for longer periods of time. Careful reflection on the content of Doyle’s work opens us up to a wider vision of who the culprits are, scaling back our anxious anger at large ominous forces and giving us pause about what we might individually do to lessen the waste stream.

But the practice of focusing attention on art’s quiet, engaging though confrontational content is only part of its remediative process.

Courtesy of Billie Milam Weisman and Michael Zakian.

Ed Ruscha’s LAX-Sunset-Malibu (1981) depicts a murky panorama of the Pacific and its famous coastal highway, with three lightly-lettered place markers barely discernable through the blackening haze. This is a land- and seascape from the dog days before the Clean Air Act would clear the smog from the atmosphere. The Weisman Museum itself perches right on the coast in Malibu, but the prospect these days is pristine, the air transparent with a healthy glow. Some things we apparently can improve. This encouraging note may be incidental, because Ruscha obviously meant to indict, not to praise. But who knows what the painter and his lurid light show hoped to instill beyond our disgust with our endless combustions? Once the universal butt of jokes about car culture, Los Angeles now leads the country in reducing pollution. How might this art have effected such change?

What this work originally stimulated was a contemplative meditation on the subject, form, and colors carefully assembled by the artist, an aesthetic experience that induced a shift in consciousness and mood. This kind of attentive, detailed viewing shifts awareness away from facts and discouraging figures about hydrocarbon production in the Los Angeles basin, now understood as a prime source of climate change everywhere. The work invites reflections on both the broadest and most personal meanings of the scene. Detailed question-asking follows.

What about that title? Ah, “Sunset” refers to the street, not just to the time of day. Viewers who have driven along Sunset Boulevard to the beach will recognize themselves in the picture, perhaps enjoying the iconic drive through downtown, to Hollywood, the Strip, Beverly Hills, and finally the Pacific Coast Highway. Confronted not with the anticipated grandeur of the ocean but a dark layer of what looks like fiery smoke, viewers can be pulled out of their presumed fascination with tourist spots and celebrity culture and realize that our “good-time” excitement itself causes the stain. This early sign of climate change spreads ominously along the coast and into our consciousness.

This realization can make us guilty, anxious, depressed. Yet we are viewing the problem at human scale, with an implied human perpetrator—us—and by extension a human remediator. We can change our ways, become more conscious of how our recreations and simple pleasures can blight the landscape, and take stock of the unseen consequences of tootling around the country clueless about its effects.

Ruscha’s painting, rather than overwhelming us with atmospheric data or depersonalizing the problem, instills a kind of calm, a slow, deliberate looking around ourselves to see what is so obviously there, but unseen. (Scientists too move into this reverie and observe and reflect before they analyze and experiment.) Art wishes to sustain that reverie as long and intensely as possible and draw personal insight and human wisdom from it.

We could go on with our aesthetic ruminations—that big blur of the sunset has a kind of beauty and power to it. What should we make of that, as we are drawn in further?

From “Environmental Impact: Selections from the Weisman Art Foundation,“ August 6 to November 30, 2014. Courtesy of Billie M. Weisman and Michael Zakian.

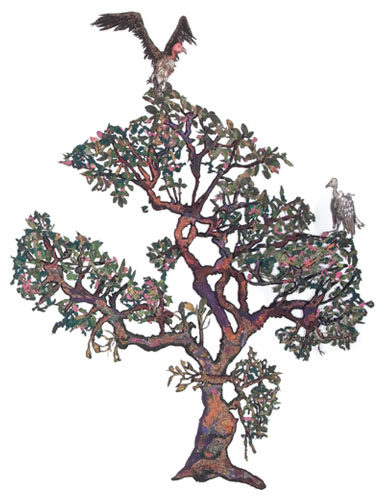

In the Weisman exhibit, Gina Phillips’s painted fabric Tree No. 2 shows a pair of vultures perching in a towering, weather-beaten tree, its autumnal shades and gnarly branches signs of desiccation. The open, two-dimensional form of the tree nonetheless evokes a Mexican Arbol de La Vida with its vibrant ceramic blossoms, fruits, birds, and religious figures. Phillips’s nearly barren, dark Tree of Death seems a perfect contrary to that devotional symbol of enduring life.

But a bit of folkloric knowledge reveals that although for us vultures stand for death and decay, they were climate-change savior birds to certain Native Americans. Coincidently, we are in Chumash territory in Malibu and it’s their story that has the vulture volunteering, after other animals fail, to nudge the Sun away from an over-heating planet—way before there were people around to cook up the place. The vulture’s once-feathered head, the fable goes, gets burned red and clean in a successful quest to stop global warming. Then we might notice that although the leaves on Tree No. 2 appear spare, some are turning red—are they about to drop off or are they newly leafing out? We might then see Phillips’s Tree as a launching platform for a contemporary climate change rescue, with the vultures as the harbinger of sustainable life.

Such latitude in interpretation might yield a whole new line of questions. Can old, perhaps totemic symbols bring us to modern activist intervention? We have a number of iconic animal figures that we use to market so-called green solutions to our energy and environmental problems: Smokey the Bear, Energy Ant, Woodsy Owl. Do we need other, multicultural animal icons to get the message across? Introducing new radical stories, tales, and myths might help illustrate our ecological dilemmas, speak to our deep fears, and carry us past them into productive engagement.

Scientific data and environmental papers rightly avoid fantasy but lack the power of mythic images and narrative to stir ordinary folks to action. Phillips’s Tree No. 2, with proper interpretation, could do just that. A rescuing vulture figure revises our assumptions about what sort of solutions we might look for—decay imagery becomes renewal energy. New areas of inquiry open and provide insights about such things as selling environmental endurance and repair to a new audience of listeners. More importantly, what we might preconceive as evidence of deterioration in our climate-changed world could become a sign of courageous rescue.

From “Environmental Impact,” traveling exhibition, September 2013 to January 2016. Courtesy of David J. Wagner.

The simplest image can spawn a cluster of reflections. Ron Kingswood’s Clear Cut is a powerful emblem of our continuing assault against the very natural elements that might actually curb the warming trend we have already induced through burning trees and other growing things. However, it can also reverberate not with resignation—that massive tree is lost—but with useful, tough instruction. Nothing is as clear and as stark as that stump topped with frigid gray snow. That’s the only thing that is clear-cut. Hardly anything else is, in trying to save trees or the planet.

We all can recommend clear-cut solutions—live simply, abandon fossil fuels, ban fracking. These cries rally activists, while at the same time they can lead to profound discouragement. The painting potently reminds us of both the swift and seemingly irrevocable consequences of destructive practices. But as well it can evoke through contrasting imagery and its title the long haul campaigns of politically shaded commitments and nuanced policy needed to change them, with very little clear cut along the way. Dealing with climate change is often an ad hoc scramble for partial solutions.

There are clear strong indictments of our environmental ruin in both exhibits, drawing us to desperate reflections about our species and the future of the planet under our control. And yet we can see alternate visions in the imaginative artistry of many works— exemplified in these two exhibits, but by no means limited to them.

All art has the capacity to open our eyes to human follies and heroics. It draws us in, arrests the subject and our own attention to it. Ecologically aware art, presented in many places and across multiple media, can shift our perspective. It can pose fresh, liberating questions and connect us to the inner consciousness of another fully engaged, sensitive human viewer of our shared problem. Such works and our conscientious practice of interpreting them can alleviate our despair through engaging their intriguing ambiguities, leading us out of our darkest thoughts and emotions.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.