This Article From Issue

March-April 2012

Volume 100, Number 2

Page 100

DOI: 10.1511/2012.95.100

To the Editors:

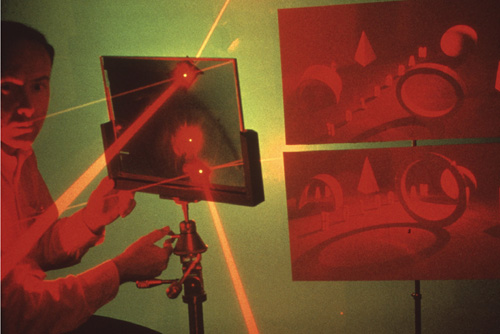

The 1965 hologram by Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks, shown in “Whatever Became of Holography” (November–December), is one of the first true holograms. But unless one moves one’s head to see “behind” the toy train, that hologram looks not much different than any 3-D image projected on a 2-D surface. Soon after this pioneering image was made, Fritz Goro, LIFE magazine staff science photographer—and my grandfather—went to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to help Leith and Upatnieks bring the concept to the public. Goro felt that their image did not convey the richness of what holograms could show: the same objects visible from almost any angle. He designed a scene of geometric solids, and with Leith and Upatnieks, recorded it on a larger-than-average photographic plate to capture a wider perspective and thus, a greater sense of three-dimensionality in the recreated image.

The scene was published in LIFE and was the first hologram deliberately designed to demonstrate its unique information-storage properties. The photograph above shows Leith adjusting that holographic plate, lit by two laser beams. Each beam reveals, at right, an image of the geometric objects from a different point of view. Later, with Steve Benton, Goro created a similar image using the so-called rainbow hologram technique, which could be viewed with a white-light source. That image was published in Scientific American. These first holograms and many more are on display the MIT Museum in Cambridge.

Thomas J. Goreau

Global Coral Reef Alliance

Cambridge, MA

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.