Rise and Fall of the Pocket Protector

By Henry Petroski

Designed to keep shirts clean and tools handy, this ubiquitous invention declined into a social stigma but rebounded as a symbol of nerd pride

Designed to keep shirts clean and tools handy, this ubiquitous invention declined into a social stigma but rebounded as a symbol of nerd pride

DOI: 10.1511/2014.108.182

At a meeting of the National Academy of Engineering some years ago, I was handed at the registration desk a copy of the program, a handsome portfolio to put it in, and a white plastic pocket protector. The protector was emblazoned with the abbreviation NAE in large capital letters, set next to a logo showing a stylized viaduct in silhouette inside a blue circle. The bridge is symbolic of the Academy’s mission “to advance the well-being of the nation by promoting a vibrant engineering profession”—in other words, to span the potential gap between the interests of the profession and those of the nation. To further emphasize this connection, the quarterly magazine of the Academy is named The Bridge and its motto is “linking engineering and society.” But does an NAE pocket protector help or hinder the achievement of this objective?

Image courtesy of NASA

The pocket protector has long been associated with engineers, but to society at large it does not necessarily evoke a positive image. According to Jeanette Madea, whose brief history of the pocket protector appears on the IEEE Global History Network website ( http://www.ieeeghn.org), the plastic pocket insert “conjures up images of a guy in a short sleeve white shirt, glasses taped together and ‘high-water’ pants.” Those reference points date the characterization to the 1950s and 1960s, when engineers did indeed favor white short-sleeve shirts, eyeglasses that were prone to break across their plastic bridge, and pants hitched up to reveal a lot of sock, often white to match the shirt. Today, we call the professional descendants of the earlier stereotypes nerds or geeks, terms that at least can include gals as well as guys.

U.S. Patent Office

Madea credits the “original pocket protector” to inventor Hurley Smith, who was born in 1908 in Bellaire, Michigan. Smith had no formal schooling but completed high school by correspondence course. After working and saving money, he matriculated at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario. He studied electrical engineering at Queens, earning his bachelor’s degree in 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression, and upon graduation had to take a job marketing Popsicles around the province. He finally found a position as an engineer with a transformer design company in Buffalo, New York, but lost this job when he refused to misrepresent the company’s rewound transformers as new products.

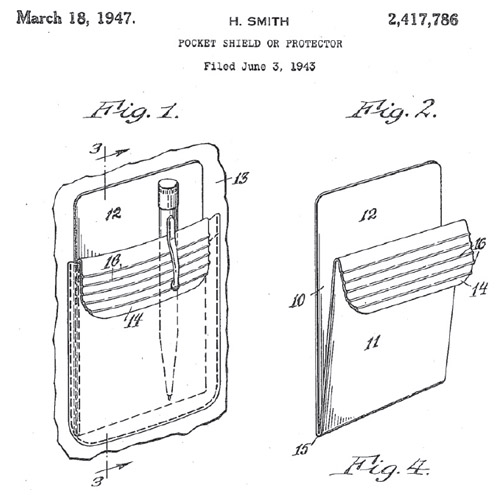

While working in Buffalo Smith came up with the idea for his pocket protector, which he patented in 1947. The time was ripe for such an invention because the ubiquitous fountain pen was notorious for leaking ink, as was the ballpoint pen then being introduced in America. According to Smith’s patent, it was not only the pocket proper that his invention protected from being “marked, disfigured or soiled by pencils or other more or less analogous articles or the fingers of the user in placing such articles in and removing them”; it also protected the material of the shirt directly above the pocket. Smith did not associate the device solely with engineers, whose fingers might be expected to be fairly clean, but also with “workers in factories,” the hands of which “may become soiled or greasy.”

As described in the patent, the manufacture of Smith’s pocket shield began with an elongated and relatively thin rectangular piece of “transparent or translucent Cellophane, Celluloid or analogous sheet material” just a bit narrower than a typical shirt pocket. The sheet was given two transverse folds. The first fold was made about equidistant from the ends, and the second—a reverse fold—about a quarter of the way from one end to produce a flap. This produced a pocket insert whose longest portion projected above the top of the pocket and whose shortest hung outside the front of the pocket. Pens or pencils clipped over the flap compressed the shirt pocket material between the flap and part of the shield inside the pocket, holding the protector and its contents securely in place. As Smith pointed out, the lightweight but stiff shield would incidentally prevent a pocket from “bagging or sagging out of shape and detracting from the neat appearance of the shirt or garment.” By clipping writing utensils over the flap, the protector also prevented wear and tear on the edge of the pocket.

Smith never claimed to have invented the pocket protector, describing his creation instead as “an improved pocket shield, guard or protector.” He emphasized instead that his version of the device was, among other things, “of novel, but exceedingly simple and inexpensive construction” and “the simplest, lightest and least expensive form of the shield.” He recognized that the open sides of the shield might be seen as a flaw in the design, for the points of pencils and pens leaning sideways could soil or poke through the shirt pocket. He answered this potential objection by illustrating an alternate embodiment, in which the shield starts out as a rectangle with wings that, after the principal folds were made, could themselves be folded around the sides and secured to the back. This additional step formed a closed pocket-within-a-pocket that was essentially what has come to be recognized as a typical pocket protector.

Image courtesy John A. Pojman

The reason Smith called his invention an “improvement” rather than a new idea is documented in the five prior patents he cited. The oldest one was issued to Allison M. Roscoe, of DuBois, Pennsylvania, in 1887 for an improvement in a “pencil-pocket” intended not to protect but to hold pencils and other objects securely in place. The device was formed in one piece of “rubber or similar elastic material.” It did have a back that projected above the top opening to form “a guide to direct the pencil, &c., into the holder when thrust quickly therein.” It also had a front flap, “to clamp the edge of the pocket and hold the device in position.” Based on the patent drawings, the Roscoe pocket appears to have been a rather bulky item. Its sides were closed, but its bottom was open, allowing longer pencils or pens to project downward. This might not be desirable if the device were to be inserted in a shallow shirt pocket, but the pencil pocket was not necessarily meant to be worn that way. As Roscoe pointed out, it could incorporate a button hole whereby it could be attached to the button of a garment such as a pair of overalls.

The second oldest patent referenced by Smith was issued in 1901 to Frank John Atkins, of Fort Madison, Iowa, for a “pencil-holder.” Like Roscoe’s pencil-pocket, the main purpose of Atkins’s holder was as an improved device to “effectively hold pencils or other articles in place in a pocket without liability of falling from the latter.” Also like Roscoe’s, Atkins’s device had a front flap. Since pencils generally were not fitted with clips, Atkins’s holder incorporated a spring sewn inside the fabric of which the insert was made. Looking like an elaborate paper clip, the spring not only clamped the insert against the garment pocket but also clamped “pencils, pens, tooth-brushes, or other articles inserted in the device” to be held securely. The rear part of the device that projected above the pocket was intended “to serve as a guard or shield to protect and prevent breakage of pencil-points.” Keeping the garment clean was not mentioned. In anticipation of later commercial applications for pocket protectors, Atkins pointed out that the covering of the spring “may have suitable advertising matter applied” to the flap or shield.

Although not cited by Smith, a patent issued in 1903 to Himan C. Dexter, of New York City, for a “pocket-protector” is closely associated with the evolution of the modern pocket protector. Dexter’s invention also incorporates a spring “to prevent escape of articles contained in a purse, pocket-case, or like receptacle.” A patent drawing shows the device holding a pencil in a jacket pocket, which could still be soiled by the pencil point because of the absence of an upward projecting back portion. The pocket-protecting feature of the invention was the way the ends of the wire spring were formed into tight eyes so that the purse, pocket-case, or garment pocket into which they were placed did not suffer wear from sharp wire ends of the insert. Hence Dexter’s invention was not the kind of benign pocket protector we have come to associate with the term.

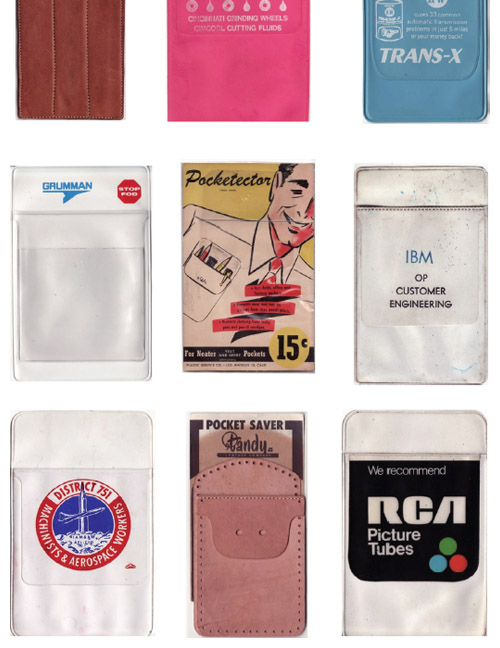

The bare-bones item evolved into a variety of forms. White was joined by custom colors and a "stealth" model.

Smith did reference a 1914 patent for a “pocket” issued to Loren Z. Coolidge of Aberdeen, Washington. The device was primarily intended to secure items in the “overalls of carpenters, bridge builders, and various other mechanics.” Once again, Coolidge relied on metal springs to hold it on the pocket and to hold rulers and other small tools in place while enabling “a mechanic to work in any position without danger of the rule falling out of the pocket.” At the same time, the device was readily removable when it was time to wash the garment. Another, 1917 patent referenced by Smith was for a pocket lining for carrying cigarettes, matches, and like items without them getting “intermixed and badly damaged.” It was to be made of “sheet metal, pressboard or other material possessing sufficient rigidity” and so anticipated Smith’s emphasis on the stiffness of his pocket protector.

Smith’s final citation was a 1927 patent by Peter Burtchaell of San Rafael, California, for a “garment attachment” that might be described as a partial pocket protector. His attachment was designed to make “temporarily stiff” the top edge of a pocket so that pens with clips could be more easily inserted into the pocket. Another purpose of the attachment was to grip the pocket so as not to become accidentally disengaged, and it was in this aspect that Burtchaell’s invention was novel. The back part of the attachment, made of “stiff and flexible material,” had “upstruck portions” that in the patent drawing look like triangular teeth. These were designed to “penetrate the material” of the shirt pocket and “prevent accidental disengagement of the shield.” Something that poked holes in the shirt hardly sounds like a pocket protector, but inventors are often so focused on the pros of their invention that they ignore the cons.

Hurley Smith made prototypes of his pocket protector by heating the plastic—using his wife’s iron, which he modified for the task—so that the material could be bent without cracking and would hold its folded shape after cooling. When it looked like he could make a living manufacturing the plastic items, Smith quit his engineering job in Buffalo and moved his family first to New Hampshire and then in 1949 to Lansing, Michigan, where he established a plastics business dealing mainly in pocket protectors. The base material had been changed to vinyl, and the edges where the front and back parts met were heat sealed. White was the standard color, which Smith could imprint with a logo, slogan, or motto covered over with clear vinyl.

Image courtesy U.S. Navy

Although Smith had patented his basic idea, it does not appear that he patented his improvements. Soon there were competing manufacturers of pocket shields. One was Gerson Strassberg, an electrical engineer by training who in 1952 was working in Brooklyn as a development engineer. As Strassberg recalled, one day a phone call interrupted his work on a bankbook cover. He was using a low-heat welding technique that employed both compression and high-frequency radio waves to fuse sheets of vinyl to make the cover. In answering the telephone, he stuck the unfinished product into his shirt pocket, where part of it flopped over the outside front of the pocket. During the phone conversation he instinctively stuck a pen in his pocket, which according to Strassberg gave him the idea for “one of the first known pocket protectors.”

By Strassberg’s own dating of events, his “accidental discovery” occurred five years after Smith’s patent was issued. Nevertheless, the invention of the pocket protector was credited to Strassberg in a 2003 article in the Orlando, Florida, Sentinel, highlighting the likelihood that a reporter writing a human-interest story involving a seemingly trivial item of commerce might not pursue the facts beyond what she was told by the subject. Whether or not Strassberg knew of Smith’s patent, he did not patent his own version of the pocket protector. Patenting anything is a basic business decision, in which the not insignificant cost of securing a patent must be weighed against the potential revenue from the sale of the item. According to Strassberg, he patented only 3 of the 200 or so products his company made, believing that “the best patent in the world is to go make a million of them and sell them quickly.”

Despite the Sentinel’s claim, Strassberg was a relative latecomer to the pocket protector business. In 1947, the year that Hurley Smith’s patent was issued, Erich Klein had started up a factory on the North Side of Chicago—now the Internet-based Erell Manufacturing—that has been described in the New York Times as “one of the first manufacturers to make plastic pocket protectors,” which it still makes. Around the same time firms on the West Coast also began getting into the business. Smith soon became aware that manufacturers were infringing on his patent, but he evidently chose not to pursue legal action because of the high potential cost of suing the numerous, geographically dispersed infringers.

Strassberg was also late in getting out of the business as most manufacturing moved overseas. In 2000, according to Esquire magazine, he believed his company was the “last pocket-protector manufacturer in America.” Along the way, the classic bare-bones item evolved into a variety of forms. Basic white was joined by custom colors, as well as clear plastic so that the color and pattern of the underlying garment can show through. There is a “stealth” model that has a clear flap and no backboard, so that it maintains a low profile in the pocket. There are also protectors with large front flaps that have sleeves into which can be inserted identification and security badges.

Wherever there has developed a large variety of any one thing, there develop also followers and collectors of the genre. The pocket protector is no exception. There is a Pocket Protector Preservation Society. There is also a Webseum of Pocket Protectors, curated by John Pojman, a professor of chemistry at Louisiana State University. This online collection contains pages of neatly arranged photos of pocket protectors displaying a variety of colors and imprintings. When I most recently visited the site I found about 1,500 unique specimens (but no NAE pocket protector among them).

Judging by the large number of pocket protectors in the Webseum that are imprinted with the names of companies, products, institutions, and organizations, the protector was widely appreciated in its heyday for its undeniable utility. There is a subset of the virtual museum’s specimens that are that and more. They are imprinted not with a commercial message but with a declaration of independence from the stigma of stereotypes. One proudly displays the Caltech seal, period. Another reads, “MIT Nerd Pride,” another simply “Nerd Pride,” and another, “Nurture Your Inner Geek.” To some observers the pocket protector may be the symbol of a stereotype, but to engineers it is an immensely practical accesory. Not only does it do what its name implies, but it can also serve as a badge of honor.

On the occasion of introducing the National Academy of Engineering’s list of Greatest Engineering Achievements of the 20th Century in February 2000, astronaut Neil Armstrong said of himself, “I am, and ever will be, a white-socks, pocket-protector, nerdy engineer.” He may not have been wearing his pocket protector when he stepped off the Lunar Module Eagle and became the first human to set foot on the Moon, but he gave engineers wearing theirs back on Earth a sense of professional pride in all that they had done. Not unlike the way the pocket protector itself was conceived, designed, and developed, they do their job quietly, efficiently, and often anonymously.

©Henry Petroski

Henry Petroski is the Aleksandar S. Vesic Professor of Civil Engineering and a professor of history at Duke University. His latest book, The House with Sixteen Handmade Doors: A Tale of Architectural Choice and Craftsmanship (W. W. Norton, 2014) will be released in May, and will be discussed briefly in the July–August Engineering column.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.