This Article From Issue

July-August 2014

Volume 102, Number 4

Page 312

DOI: 10.1511/2014.109.312

LOST ANIMALS: Extinction and the Photographic Record. Errol Fuller. 256 pp. Princeton University Press, 2014. $29.95.

If Edward Gorey had written a Dr. Dolittle book for grown-ups, the result might have been something like Errol Fuller’s natural history page-turner Lost Animals. It presents a unique trove of photographs featuring extinct birds and mammals. The creatures Fuller describes exhibit fantastic, even whimsical, traits. A bat that folds up its wings and scampers about on the ground for its food. A carnivore that looks exactly like a striped dog but is actually a marsupial. A nearly blind freshwater dolphin with a long, thin beak that appears designed for spinning plates at the tip.

The creatures Fuller describes exhibit fantastic, even whimsical, traits.

Yet each wonder collected comes with its own grim story: Habitat-decimating natural disasters, feathers or horns coveted by humans, epidemics, invasions of nonnative species. Occasionally, the reason for a species’ demise is unknown. More often, misfortunes combine into a lethal web of circumstances. Fuller conveys the pathos of these losses. More than once among the tales of this luckless menagerie, a ban on hunting is put in place years after the animal was sighted for the last time.

Fuller clearly had his work cut out for him in finding and gathering these images from museums and private collections around the world. But the search had thrilling moments, too, as when Fuller came across the first known photo of an Aldabra brush warbler: “Despite its rather unspectacular aspect it was the grail of extinct-bird photograph hunters—a hitherto unknown photo of a virtually unknown species that had lain in the drawer of its owner for 20 years or so.” Some of the book’s photographs were taken by people who knew their images captured an endangered creature—occasionally the last known of its kind, as with Martha, a captive passenger pigeon pictured on her perch. In other cases, the occasion was more casual, and the person behind the camera likely had no idea how significant the photo would eventually become.

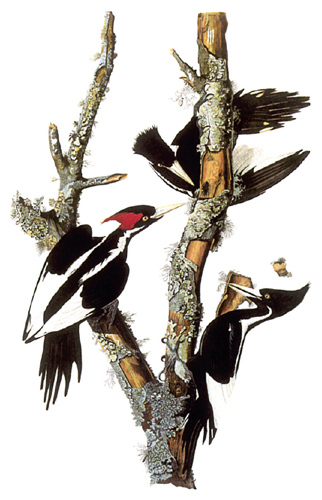

From Lost Animals.

In the book’s introduction, Fuller notes that not all of the pictures are clear or even conventionally “good.” That they exist at all is wonder enough, given the difficulties of early photography and the remoteness of some of the species’ habitats. The only reason why we can view these animals today without the mediating hand of an illustrator is that they endured until sometime after the development of photography. Hence even the blurrier photos have a marvelous documentary quality. (The book includes an appendix with color illustrations of some of the species pictured in the book. This is especially handy for viewing vivid animals, such as Australia’s paradise parrot, of which only black-and-white photos survive.)

From Lost Animals.

In the wrong hands a book like Lost Animals could be a wan march through a morbid family album, and there are certainly moments when the cumulative loss of these creatures seems overwhelming. But Fuller’s knowledgeable, compassionate, and occasionally humorous narrative carries the day. (Of unsatisfactory images that emerged about ten years ago allegedly depicting the ivory-billed woodpecker, Fuller writes, “For all that any ordinary person could tell, the pictures might have shown a garden gnome riding on the back of the Loch Ness Monster.”) It takes a steady guide to lead readers through such territory, and Fuller proves up to the task.

In The Story of Dr. Dolittle, an admiring friend compliments the doctor on a book he authored about cats, words that apply perfectly to Fuller’s efforts in Lost Animals as well: “It’s wonderful—that’s all that can be said—wonderful. You might have been a cat yourself.”

Dianne Timblin is interim book review editor for American Scientist and author of the poetry chapbook A History of Fire (Three Count Pour, 2013). Her ongoing series of lo-fi collages may be found at Art of Salvage.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.