This Article From Issue

January-February 2001

Volume 89, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/2001.14.0

Pandora's Picnic Basket: The Potential and Hazards of Genetically Modified Foods. Alan McHughen. viii + 277 pp. Oxford University Press, 2000. $25.

Because all organisms share a common genetic language, DNA, a gene for a desirable trait can be taken out of one organism and inserted into another, where it will be read and properly understood even if the new host is an unrelated species. Genetic engineering of this sort has become routine. For example, the genes producing beta carotene (vitamin A) in daffodils have been transferred to rice to make it more nutritious; bacterial DNA that codes for proteins toxic to insects has been transferred to corn, potatoes and cotton to control important pests. An organism that has gained new genetic information from the addition of foreign DNA is described as genetically modified (GM) or transgenic.

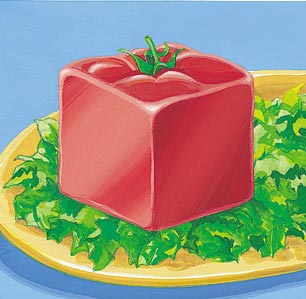

Tom Dunne

The technology used to genetically modify organisms has agricultural, medicinal, industrial and environmental applications, but protests against it have focused primarily on food and agriculture. Since the commercial debut of transgenic crops and foods in the mid 1990s, environmental activists and consumer advocacy groups have severely curtailed commercialization in Britain, France, Germany and Switzerland, and similar groups are now gaining ground in the United States. Critics of GM foods argue that the long-term effects of the technology have not been studied adequately, that the food itself or the environmental release of the modified organism could have unintended adverse effects (such as allergic reactions, increased resistance to antibiotics and environmental threats), and that GM foods should be labeled to allow consumers to avoid them if they so choose.

Most popular books on the subject are decidedly opposed to genetic modification of crops. In Pandora's Picnic Basket, Alan McHughen argues that a rational debate on the risks and benefits of GM foods should focus on the science behind the process and products. His goal is to dispel the myths about genetically engineered crops and provide background knowledge that will enable readers first to form their own opinions about the technology as a whole and then to evaluate the benefits and possible risks of individual GM products from a scientific point of view.

McHughen is a senior research scientist at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada, and chair of the International Biosafety Advisory Committee of the Genetics Society of Canada. As a plant breeder, he has extensive experience with both conventional breeding and the development of transgenics; he has firsthand experience with the scientific, political and regulatory issues relating to GM foods. In this book he addresses the key issues brought up in the popular press: Are GM crops safe? Do they pose a threat to the environment? Should GM foods or products containing them be labeled?

I found McHughen's insights, opinions, personal accounts and occasional ramblings to be engaging and informative. He doesn't pull any punches, exposing the miscalculations of multinationals developing and marketing GM organisms, the hasty reporting of research findings without careful peer review, the flawed reasoning behind pollen-escape studies performed before environmental release, the problems that may lie ahead with labeling of foods containing GM products and the inherent flaws of the regulatory approval process.

McHughen theorizes that public reaction to GM organisms has been stronger in Europe than in North America because of widespread distrust of government regulatory agencies in Europe, the perception that agricultural intensification is undesirable and a threat to wildlife there, and a diffuse distrust of any genetic manipulation because it stirs up historical fears of social engineering.

McHughen tries to avoid jargon and technical details, except in the tutorials and primers on molecular genetics, genetic engineering and plant breeding that he provides early in the book. Although these are simplistic, they are probably still too technical for the average reader?which is unfortunate, since they are essential to understanding his viewpoint. He provides no references throughout, presumably to put readers without a scientific background at ease. The absence of any references at first made me discount the content, but as I read farther, I relaxed and adopted a more generous perspective: McHughen has a broad knowledge of the scientific literature that forms the basis of his arguments, but he also knows that this is a debate in which science gets distorted; thus his style is to roll up his sleeves and talk plainly. Pandora's Picnic Basket is not meant to be the definitive treatise on agricultural biotechnology; rather, it is McHughen's attempt at a rational discussion of this technology.

In the end, McHughen predicts a steady demystification of GM organisms in the marketplace: At first, GM, conventional and organic produce will be offered for sale in separate bins, but ultimately advertising and packaging will loudly announce revolutionary new attributes made possible only by genetic modification.

If I see one deficiency in the book other than the lack of references, it is that it focuses too much on controversy, with scarce mention of many potential beneficial agricultural applications of genetic engineering: Transgenic crops can be developed for pest resistance, improved yield, tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses, use of marginalized land, improved nutritional content and the production of vaccines and pharmaceuticals. Such applications are likely to be of critical importance in the fight against disease and malnutrition in developing nations.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.