What We Get Wrong About the Evolution Debate

By Adam Shapiro

The prevailing narrative juxtaposes science and religion—but this approach erases the root influences of social inequality and racism.

February 12, 2019

Macroscope Biology Evolution

As a historian of American science who wrote his first book about the Scopes trial, I admit I’m sometimes nostalgic for the days when the biggest controversy in science disbelief was evolution. Today, as antivaccination hoaxes are inspiring new outbreaks of deadly diseases and denying the human causes of climate change threatens the well-being of the planet, creationism feels almost quaint. Annoying, but without an obvious body count.

It may feel like we’ve moved on from this issue, but evolution controversies are still widespread in the United States. In the past decade, dozens of state and local efforts designed to limit the teaching of evolution or to enable schools to present alternatives have been introduced across the country, with varying degrees of success. Surveys from organizations such as Gallup and the Pew Research Center show that a sizable proportion of the American public does not agree that humans evolved. (More on these surveys later.) More people dispute human evolution than take issue with either vaccine safety or human-induced climate change.

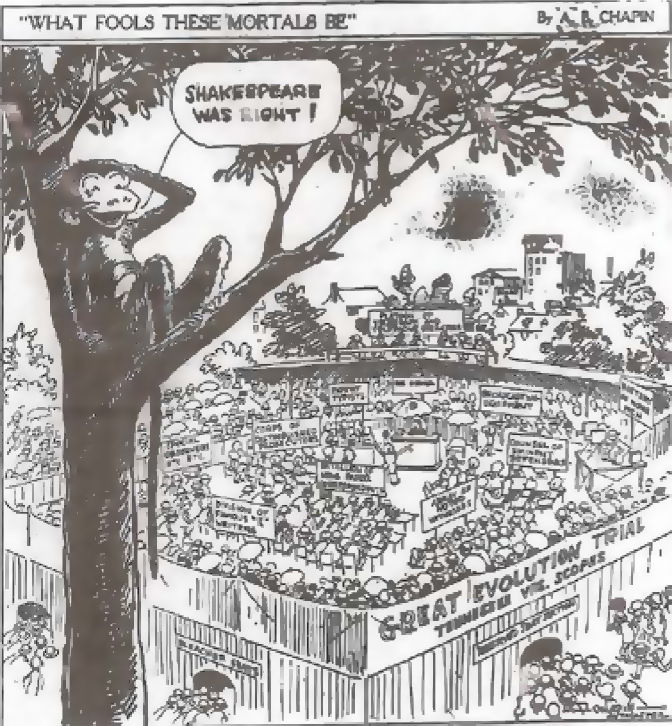

Cartoon republished in Robinson, S. R., 2018; originally published in The Richmond Planet on July 11, 1925.

Nonetheless, the evolution debate seems less urgent. When I interviewed organizers of the 2017 March for Science, nearly everyone I spoke with mentioned climate policy as a primary concern. Some also mentioned the dangers of antivaccination, but almost no one mentioned evolution as a motivating issue. In part, this can be explained by the belief that antievolutionism is less immediately harmful, but there is also a prevailing sense that it is fundamentally unlike other forms of science denial: driven not by greed or political power, but instead by religion.

Two publications from the Pew Research Center last week highlight just how pervasive this assumption is when it comes to questions about evolution and religion. One report demonstrates how the phrasing and sequence of questions about attitudes regarding evolution significantly influence survey results. When people were first asked to choose between only two options—that humans evolved or that they have always existed in their present form—and only to differentiate between a God-guided interpretation of evolution or an atheistical one as a follow-up question—a higher percentage of respondents chose creationism than in a survey in which three options (atheistical evolution, theistic evolution, and creationism) were all presented together.

More people dispute human evolution than take issue with either vaccine safety or human-induced climate change.

One might see this as evidence that some conflict-averse people are inclined toward a middle ground when presented with one. But this begs the question of why anyone would see God-driven evolution as a middle position. At the time that Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species, some of his readers opined that a creator who could set the world in order that it could unfold in such diverse and intricate ways over eons implied a “loftier” more powerful and purposeful deity than one who created separate species on an ad hoc basis. To them, theistic evolution wasn’t a “middle ground” but a testimony to an even greater God than they’d previously imagined. Today, however, theistic evolution is often presented as an insincere detente between polar opposites, to be derided as incoherent by biblical creationists and New Atheists alike. William Jennings Bryan once described this middle ground “as an anesthetic which deadens the patient's pain while atheism removes his religion.” The Pew survey is designed to reinforce this view.

Last week Pew also published a brief history of the evolution debate in the United States that makes this conceit even clearer. It asserts, without citation or evidence, that the persistence of controversy over evolution “lies, in large part, in the theological implications of evolutionary thinking.” The opening paragraph concludes: “Roughly half of the U.S. adult population accepts evolutionary theory, but only as an instrument of God’s will.” This language implies that “accepting evolutionary theory” is morally correct but that doing so while also believing in religion is better than being a creationist, but incomplete—as one might expect a vegan to chide a vegetarian who won’t stop eating cheese.

There is a prevailing sense that the evolution debate is fundamentally unlike other forms of science denial: driven not by greed or political power, but instead by religion.

When writing history, just as in designing a public opinion survey, a lot of presupposition goes into how questions are framed. Of course the history of evolution in the United States includes debates over “the theological implications of evolution.” But focusing on a narrative that centers people who only see the evolution debate in science-religion terms, and whose objections to evolution are rooted in conflict with the Bible, is a willful decision to erase many people who were actually more directly impacted by these debates.

The evolution concept was controversial even before Darwin put his theory into writing. In the wake of the French revolution, the idea that people could change—whether it was due to influence of the environment or through the benefits accrued in their lifetime being passed down to next generations—was seen as a radical antidote to conservative ideas of hereditary nobility and social caste. Contrary to the Pew history assertion that “the publication of ‘Origin’ went largely unnoticed” in the last months before the Civil War, some of his first readers in the United States were strident abolitionists (including financial backers of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry) who saw in Darwin’s work biological evidence that racial differences were not immutable.

The history of American controversies over evolution has long been entangled with the history of American educational racism.

Darwinism did become freshly controversial in the 1910s and 1920s, leading to the famous Scopes trial. But it wasn’t because people suddenly noticed that evolution was incompatible with a 6,000-year-old Earth after Darwin’s books had been around for half a century. In the 1910s and 1920s, new forms of science education arose that were designed with urban immigrant children in mind, pushed into an expanding school population as rural states sought to modernize and industrialize. Opponents of social reform, nativists and those who reviled the state’s influence over culture didn’t just oppose evolution, but were quick to seize upon convenient biblical rhetoric to take the moral high ground in their fight. But this was neither the only religious reaction nor the only educational reaction. As Shantá R. Robinson notes in her recent study of Black-published newspapers of the era, the acceptance of evolution by many Black Protestants, while not universal, was conditioned by a belief in social progress as well as skepticism of the segregated power structures that existed in 1920s America. Indeed, the history of American controversies over evolution has long been entangled with the history of American educational racism. The court rulings of the 1960s and 1980s striking down creationism provisions were derided in Southern states as further instances of federal court interference in local educational matters that had been heard since Brown v. Board of Education and subsequent desegregation cases. Today the evolution issue is used to fuel a growing industry supporting homeschooling organizations and religiously affiliated private and charter schools—some of whom recreate in the private sector the conditions of segregation that courts sought to end in public schools.

The science-religion narrative reinforces the idea that some of the more recent—and more dangerous—issues of science denial have nothing to learn from one of America’s oldest.

By accepting and reinforcing the narrative that the evolution issue in America is driven by the theological implications of Darwin, not only are the views and voices of those who aren’t primarily white conservative Protestants left out of the story, but the dynamics of political and social power, of profit and the education industry, are occluded from our understanding of the debate. This narrative reinforces the idea that some of the more recent—and more dangerous—issues of science denial have nothing to learn from one of America’s oldest. This science-religion narrative isn’t just written into the history, it’s reflected in the surveys that measure current affairs. Pew doesn’t ask people whether they believe climate change was caused by God instead of by humans. They don’t ask whether vaccines prevent disease more than prayer. We might find it absurd if they did. It’s only the evolution issue in which science is juxtaposed with religion. Instead of nostalgia for the days of Dayton, Tennessee, and Dover, Pennsylvania, I’d prefer to see a future in which we treat the public understanding of science with the complexity and seriousness that it deserves.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of American Scientist or its publisher, Sigma Xi.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.