This Article From Issue

March-April 2004

Volume 92, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/2004.46.0

The Herschel Partnership: As Viewed by Caroline. Michael Hoskin. viii + 182 pp. Science History Publications Ltd., 2003. $40.

Caroline Herschel's Autobiographies. Edited by Michael Hoskin. viii + 147 pp. Science History Publications Ltd., 2003. $40.

William Herschel, dean of late–18th-century observational astronomers, is a stock entry in elementary astronomy texts. They duly describe his telescopic discoveries, which opened whole new vistas in the subject, but usually only mention in passing that in the course of making these observations he was ably assisted by his sister Caroline, who herself discovered several comets. But thanks to Michael Hoskin, we now have two new books—The Herschel Partnership and Caroline Herschel's Autobiographies—that bring vividly to life the whole story of the intertwined and at times tumultuous lives of these siblings.

They were born in Hanover—William in 1738, Caroline in 1750. Their father was an oboist in the local Foot Guards, and their mother led a life based in the kitchen, taking interest in little else. Their father's genes prevailed, however, and several of the family's 10 children, including William and Caroline, showed both an interest in and a talent for music. William was encouraged in this pursuit, but Caroline was kept as a kitchen drudge by her mother, who foiled every effort by her daughter to achieve independence as a governess through an education in music and languages. This situation developed in Caroline a lifelong fear of being unable to fend for herself, which was intensified by her small stature, her plain appearance and a bout with smallpox that left her "totally disfigured" and damaged in the left eye. William eventually rescued her from this situation and brought her to England to join him first in a musical career and later in an astronomical one.

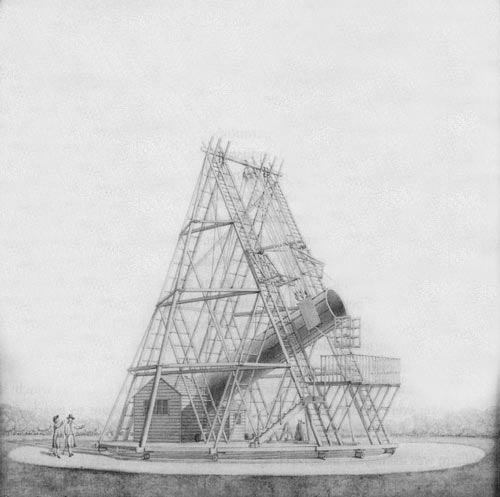

From The Herschel Partnership.

It is an indication of Caroline's complexities that she wrote two autobiographies, one when she was in her 70s, the other in her 90s. She started the first when William's life was nearing its end, her intention being to tell something of their lives to younger members of the family. But she abruptly broke off writing the autobiography when she came in her account to William's late marriage (at age 49), which evidently had embittered her greatly, despite bringing her a pleasant and considerate sister-in-law. We lack any details of her feelings then, because she later destroyed everything she had written in her diary of that time, perhaps realizing later how unjustified her remarks had been. The second autobiography, started when she was 90, was intended for her much-loved nephew John, William's son. She kept at it for another five years, but in the end once again broke off when she got to William's marriage, even though she was by then writing kindly and enthusiastically about John's mother in her letters.

These autobiographies, edited by Hoskin, are published here in full for the first time. They will be of much use to professional historians looking for particular details.

The Herschel Partnership is an able introduction to the autobiographies that essentially summarizes Hoskin's own previous scholarship. The book will surely find a wide readership: It is easily the best detailing of the two Herschels, brother and sister, that has ever been written. On the one hand, it is packed with anecdotes and details of their lives; on the other, Hoskin illuminates the significance of the science they were doing. He excels particularly at showing how William's nonacademic background allowed him to approach astronomy in entirely new ways. This is science writing at its very best.

A random sampling of anecdotes might include William as a teenage oboist in the Hanoverian Guards taking cover in sodden ditches and under hedgerows while musket and cannon balls hurtled overhead. Years later, in England, William's great success as a musician, singer and composer (some of his delightful symphonies are now available in Super Audio CD format from Chandos Records) gave way to a growing interest in astronomy.

From The Herschel Partnership.

Unable to find a telescope large enough for his needs, he bought some books on casting and grinding mirrors, rolled up his sleeves and eventually produced telescopes that in later side-by-side testing proved much superior to anything available to the Astronomer Royal at Greenwich. After discovering the planet Uranus and giving up his musical career to become the king's personal astronomer, he moved, with Caroline, to Slough to be near the king at Windsor Castle. This led to many interrupted dinners when a knock on the front door presaged the royal family and a bevy of dukes and ladies come for an evening of entertainment at the telescope. On one such occasion they brought the elderly archbishop of Canterbury, who had some difficulty ascending the ladder to the telescope's eyepiece. The king leaned back to lend a helping hand. "Come, my Lord Bishop," he said, "I will show you the way to Heaven."

Many stories reveal Caroline. As night assistant to William, she was usually at an open window of their house writing down positions and descriptions of objects as called out by William, who was outside at the telescope. On one such night, with the temperature at 13 degrees Fahrenheit, William asked her to bring him something in a hurry. She raced over, slipped in the snow and impaled her leg on a butcher's hook that was part of the telescope's undercarriage. William and his assistant rushed to lift her off, she reports, leaving "nearly 2 oz. of my flesh behind." Neither William nor the assistant nor the assistant's wife knew what to do, "and I was obliged to be my own surgeon."

But Caroline's contributions far exceeded staying up nights to record data. Usually the next morning saw her busily organizing her notes, copying out earlier published papers, rearranging tables in more convenient form, or editing William's material for publication. It's hard to say what his eventual reputation would have been had she not been there to help him. And not to be overlooked as an observer, Caroline became a comet hunter par excellence herself.

I strongly recommend these books for the light they shed on both the scientific significance of this partnership and its human dimension.—J. Donald Fernie, Astronomy, University of Toronto

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.