This Article From Issue

July-August 2001

Volume 89, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/2001.28.0

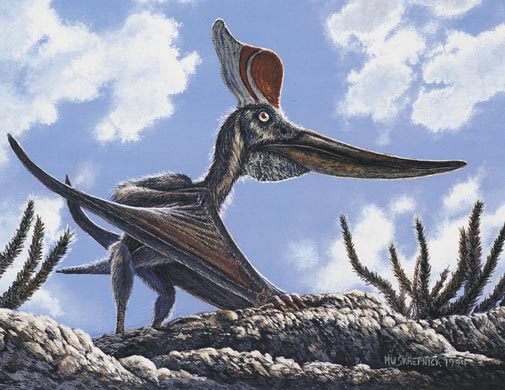

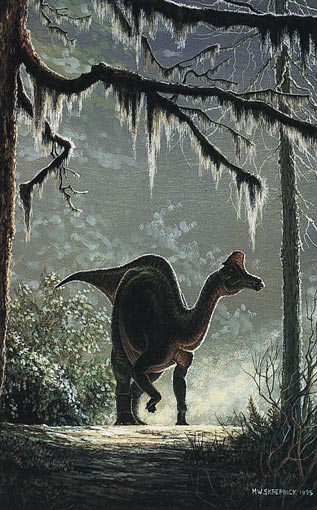

After a lifetime of walking with dinosaurs, I found my attention riveted by the paintings and sculptures from the collection of John J. Lanzendorf reproduced in Dinosaur Imagery: The Science of Lost Worlds and Jurassic Art (foreword by Philip J. Currie and photography by Michael Tropea; Academic Press, $49.95). These images demonstrate that restorations of dinosaurs are becoming more lifelike and that the animals were indeed otherworldly.

The works of art are arranged by geologic age depicted and portray dinosaurs as intermediate between reptiles, on the one hand, and birds and mammals on the other. Many are accompanied by commentary from a paleontologist, highlighting the tension between the analytic viewpoint of a scientist and the synthetic perspective of an artist.

Dinosaur Imagery: The Science of the Lost Worlds and Jurassic Art

Dinosaur Imagery: The Science of the Lost Worlds and Jurassic Art

The art tempts one to generalize, stimulates reflection and focuses the reader on what, really, was a dinosaur. Do we have it? Is there anything missing—the distortion of a foot supporting a massive or accelerating body? the quasi-familiar details of ancient insects and plants? the smells, sounds and moods of the "former world" in which natural selection shaped the dinosaur?

Dinosaur Imagery: The Science of the Lost Worlds and Jurassic Art

Dinosaur Imagery: The Science of the Lost Worlds and Jurassic Art

What do the pieces tell us of ourselves? Tyrannosaurus rex is the most popular dinosaur. Two-thirds of the dinosaurs illustrated are raptors or large carnivores, and more than half of the herbivores are objects of impending or actual carnivory. Bird dinosaurs and dinosaurian herds are not as effective in capturing imaginations. Dinosaurian environments entirely vanish in sculpture. We have not yet exhausted the implications of the dinosaurian world.—Dale A. Russell, North Carolina State University and the North Carolina

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.