Exquisite Control

By Roald Hoffmann

Precisely guiding chemical reactions at the molecular level

Precisely guiding chemical reactions at the molecular level

DOI: 10.1511/2000.15.14

The chemical reaction should go, but refuses to do so? Bang on it—with heat, with light, with pressure. Or, so much better, find a catalyst—an ingenious partner in a reaction that cuts down an energy hill that is in the way, or gets involved with the reactant molecules, takes them in hand, so to speak, and guides them in a path around that hill. And then the catalyst is regenerated.

The giant chemical industries of the world offer testimony to our skill at devising ways to make reactions go in ton lots. And yet we would like to exercise still greater control over what happens. For instance, it's no sweat to break the weakest bond in a molecule. But what if the bond we want to break, and no other one, is not the weakest? In this, the last of four Marginalia on contemporary chemical dynamics, I look at some fascinating developments in precisely guiding chemical reactions at the microscopic, molecular level.

The direction may take different forms. Energy in molecules is distributed in their motion (translation), and also in their internal vibrations and rotations. Molecular beams and lasers allow chemists to select very precisely the way a molecule is tweaked—for instance the excitation may be neatly deposited in one vibration. Having prodded the reactants in a very specific way, we can look at what happens to the reaction products. Which bond is energized? Which bond is broken, which formed? Let me begin with one remarkable and simple reaction that has been studied in this way.

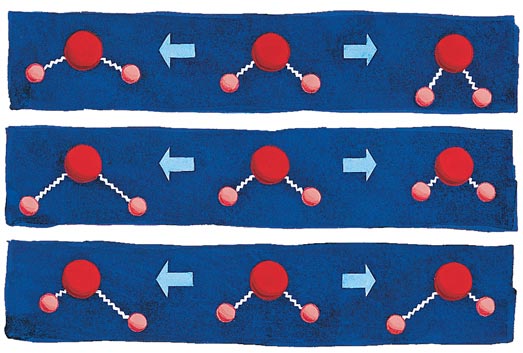

For the longest time chemists had been foiled in trying to put energy into a molecule in a selective way. It's clear that just heat, which is the totality of collisions between molecules, is indiscriminate. But one might have thought that using light to excite one particular vibration of a molecule would work. Which vibrations? In Figure 2 are shown the three "normal modes" of vibration of a triatomic molecule, water. It looks like the asymmetric stretch might break an OH bond. But no, inject a dollop of energy (from an infrared laser) into just that vibration, and the energy is just quickly randomized among all the vibrations.

Tom Dunne

Standing in a quiet, burned-out homesite overlooking the coastal town of Santa Barbara, California, six years after flames tore through this community in 2009, the sense of both terror and loss were still palpable.

One can also affect a reaction's outcome by choosing the way reactants approach. This is done by firing beams of gaseous reagents at each other, in which one or both of the reaction partners is at least partially aligned in a specific way. The control one may thus achieve on reaction geometry is impressive; it is also something one cannot do in the liquid state. Let me show you an example that blends molecular beams and selective excitation.

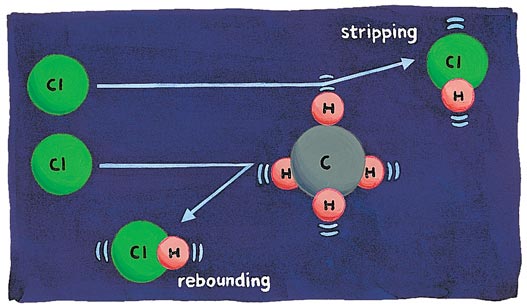

The first reaction encountered in organic chemistry texts is likely to be the chlorination of hydrocarbons. The important, rate-limiting "chain-propagation" step in that reaction (for, say, methane) is Cl + CH4 → CH3 + HCl. Zare's group recently found a remarkable result in their study of this old chlorination reaction. When the reactants just collide, even if the Cl atoms move in quickly (actually they are fired in), the reaction is difficult. To make the reaction go, a direct hit (in the trade this is called a "small impact parameter") is needed, and this is hard to arrange, for the molecular bullets are very small, metaphorically speaking.

That HCl comes off "backwards" relative to the incoming Cl is understandable. Says Zare, "It's just like three billiard balls of the same mass all colliding in a line, in which the incoming ball nearly stops and the one at the other end takes off in the same direction." In what we call a center-of-mass system, the HCl (made up of the Cl billiard ball coming in and the H hit first) would be going "back," rebounding, viewed from the CH3 fragment.

To make the collisions more effective, the laser chemists excite selectively and strongly the C–H stretching vibration of methane, CH4. Now a lot of HCl is formed (the rate of the reaction increased by more than a factor of a hundred); obviously even glancing collisions are effective. And much of the HCl product moves in the same direction as the incoming Cl. What has changed? Well, the highly excited C–H bond is stretched a lot. It is more likely to be on the "outside" of the rotating CH4 target that presents itself to the incoming Cl atom (Figure 3). The target for the arrow is effectively bigger, much bigger. And the Cl sweeps along the hydrogen whose bond had been weakened by vibrational excitation, stripping it from the methane.

The preceding examples have shown how energy specifically deposited in the vibrations of a bond or a molecule may dramatically alter the course of a reaction. What follows is a fascinating example of the "microscopic reverse," molecules vibrating in finely defined ways as a consequence of a chemical reaction.

In an earlier Marginalium, I wrote of scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) images showing us molecules in stages of catalysis; in another, I described femtosecond spectroscopy "freezing" molecules in the act of falling apart or coming together. Experiments whose output is a graphic image have immense power; the experiment I am about to describe images quite directly the products of a chemical reaction flying apart.

Paul Houston and his colleagues at Cornell have been looking at what happens when ozone is dissociated in the near ultraviolet, just the region in which ozone optimally shields us from much of the sun's ultraviolet. The Cornell chemists follow one mode of decomposition, into a certain spin state (triplet) of both O2 and O:

O3 yields O(3P) + O2(3Sg–)

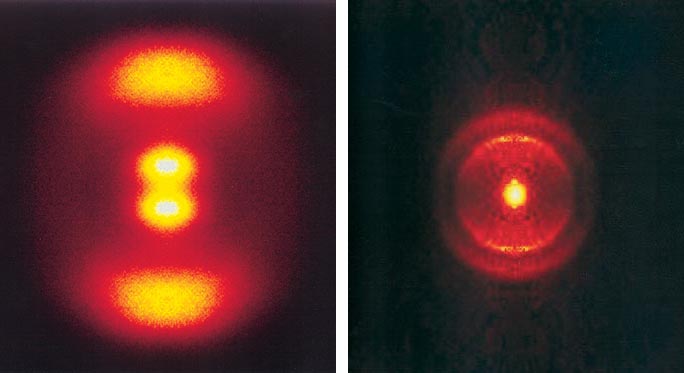

The fragments travel away from each other, preferentially along a specific direction that is roughly along the extension of what was an unbroken O–O bond of the parent ozone. In this case the oxygen atoms are detected—the brighter (more yellow) the area in Figure 4, left, the more oxygen atoms strike there; the farther from the center of this pattern, the faster moving the oxygen atoms.

The peaks at top and bottom in this roughly resolved image were expected—lots of fast moving O atoms. What was startling was that there were also some slow-moving O atoms (the vertical dumbbell near the center).

Next, conservation of energy comes into play. Knowing the energy in the light, the energy needed to break the O–O bond in ozone and the kinetic energy borne by the fleeing O atom, one can calculate the energy left behind in the unobserved O2 (actually that energy can be measured in another experiment). Lots of energy in O (outer peaks in Figure 4, left) means little energy in O2. Little energy in O (inner peaks in Figure 4, left) implies that there's a lot of energy in the O2 molecule left behind.

A lot is a lot—indeed enough to put the O2 into its 27th and 28th overtone, nearly enough to knock it apart. That's remarkable. The fine-resolution image at right in Figure 4 shows well-defined "halos" that are the result of molecular vibration being quantized—one "halo" corresponds to O atoms that have left behind an O2 in the 27th vibrational overtone. The other halo, further in, is due to the slower O atoms that leave behind the O2 in the 28th overtone.

The degree of control that chemical dynamicists are beginning to exercise is startling. I love the understanding that emerges. There is also something else that appeals to me personally, both as a quantum chemist and as a builder of conceptual bridges; each of these experiments is not only a tour de force of high vacuum technology, optics and electronics—but also a wonderful blend of quantum and classical mechanics. There is no way to understand the chemistry of molecules reacting without moving in both worlds.

Let me elaborate: The molecular beam machines (I've spared you the cost of these) operate on classical billiard-ball logic; the same way of thinking lets us see molecules colliding, fragments bouncing off in certain directions. Simple and foolproof conservation of energy was at work in the Houston experiment. But at the same time, to understand these ingenious experiments one must think in the beautiful and sometimes mysterious logic of quantum physics—think of the uncertainty relationship shaping the wave packets and time resolution in femtosecond spectroscopy, the quantum helicity I described in one Marginalium, the tunneling current that makes STM possible. The laser, that tunable jack-of-all-trades source of strong light, owes its coherence and power to a quantum effect; the energy level spacing that is behind the laser also explains state selection.

Chemical dynamics, the kinetic art, exemplifies in every one of its experiments the intersection of the classical and quantum worlds. It is the realm of the quantum mechanic, just as much as it is of the clever instrument builders. Who are getting to know, finally, what makes chemistry run.

© Roald Hoffmann

I am grateful to Paul Houston and Dick Zare for their comments and encouragement, and to Andrea Ienco for help with the drawings.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.