This Article From Issue

September-October 2009

Volume 97, Number 5

Page 428

DOI: 10.1511/2009.80.428

“There is no single ‘best’ view of an egg,” photographer Rosamund Purcell writes. “It is endless. It has no front or back—no boundaries—and any number of possible horizons.” In Egg and Nest (The Belknap Press, $39.95), Purcell brings her attention to eggs, nests and birds from the collections of the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology, in Camarillo, California.

From Egg and Nest.

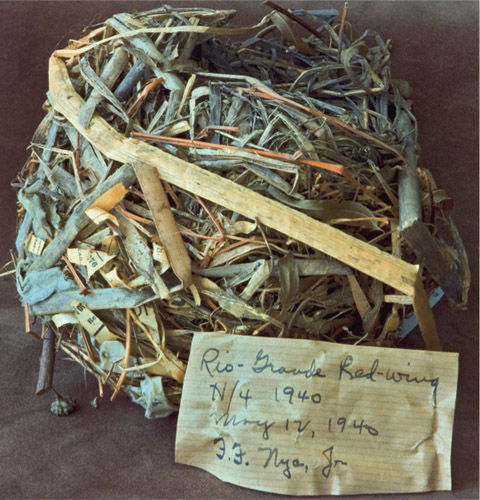

The book consists of 10 groups of photographs, rendered in natural light in simple, striking settings. The most engaging plates contain many layers of meaning: The nest of a red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) was made with strips of newspaper as well as twigs and bits of cloth; the collector’s note is also shown, written with a distinctive hand on fine-lined, yellowed paper. We can picture a blackbird peering down on the people of the 1940s town where the newspaper was printed, the concerns of those people, the thoughts, hopes and habits of the oologist who collected the nest.

Linnea S. Hall and René Corado, who direct and manage the foundation, note in an introductory essay that removing eggs and nests from the wild is now illegal in most places, and permission to do so for research purposes is limited. They express the desire to maintain existing collections to help our understanding of bird biology and changing ecosystems. All the same, it’s hard not to feel some unease, along with wonder, on encountering so many specimens of bird life—in just a small sample of the collections.

The eggs of a white-chinned prinia (Schistolais leucopogon) display delicate pastel blotches; a close-up photograph reveals the hole made to remove the contents of one egg, and the collector’s inked-on identification code. The contrasts between these markings—the bird’s ephemeral blue and pinkish-purple dots, applied as the egg passes through the oviduct; the collector’s precisely drilled hole and dark black script—evoke the tension inherent in collecting the stuff of the animal world.

In another image, red-winged blackbird eggs rest on squares of cotton wool, their many shades of sky blue recalling the diversity possible within one species. Egg and Nest subtly suggests that such variety deserves our care: for the artifacts and, crucially, for their present-day relatives.—Anna Lena Phillips

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.