Farming and the Risk of Flash Droughts

By Jeffrey Basara, Jordan Christian

In the coming decades, every major food-growing region faces increasing incidences of sudden water shortage.

In the coming decades, every major food-growing region faces increasing incidences of sudden water shortage.

Flash droughts develop fast, and when they hit at the wrong time, they can devastate a region’s agriculture. They’re also becoming increasingly common as the planet warms.

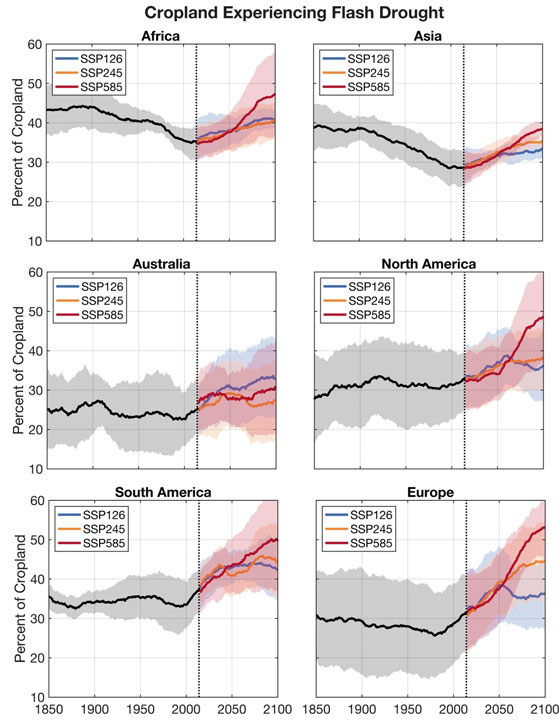

In a study we published this year in the journal Communications Earth and Environment, we found that the risk of flash droughts, which can develop in the span of a few weeks, is on pace to rise in every major agriculture region around the world in the coming decades.

In North America and Europe, cropland that had a 32 percent annual chance of a flash drought a few years ago could have as much as a 53 percent annual chance of a flash drought by the final decades of this century. That result would put food production, energy, and water supplies under increasing pressure. The cost of damage will also rise. A flash drought in the Dakotas and Montana in 2017 caused $2.6 billion in agricultural damage in the United States alone.

All droughts begin when precipitation stops. What’s interesting about flash droughts is how fast they reinforce themselves, with some help from the warming climate.

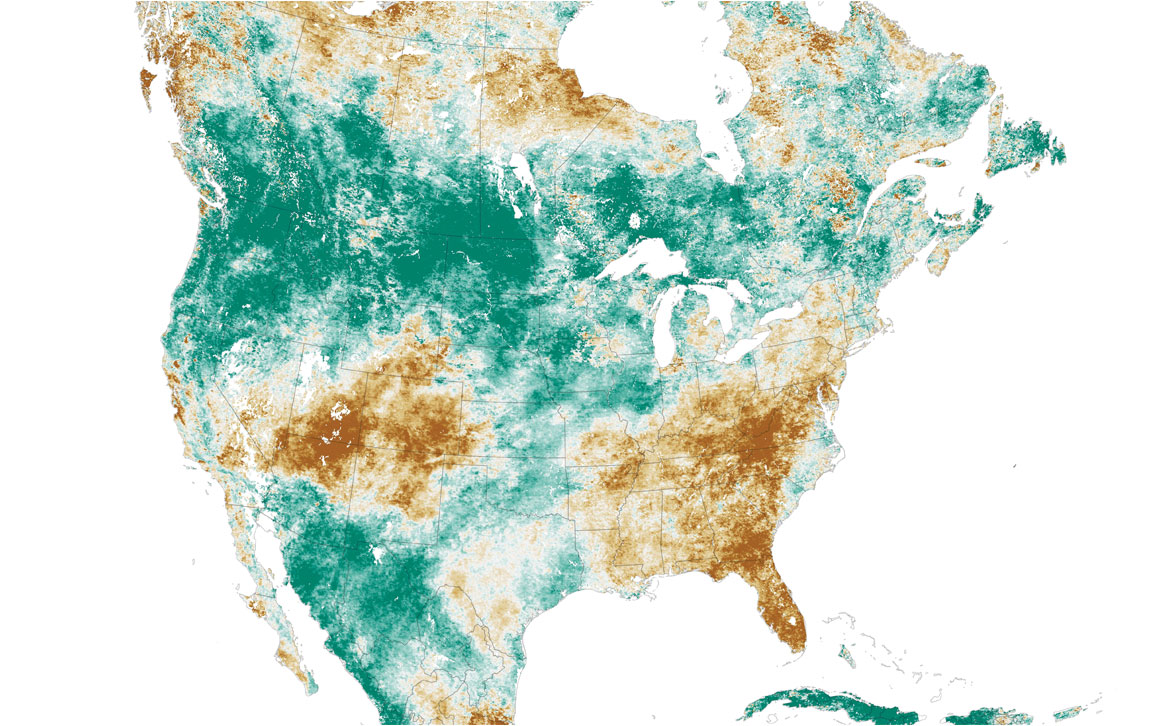

NASA Earth Observatory/Lauren Dauphin/Christopher Hain

When the weather is hot and dry, soil loses moisture rapidly. Dry air extracts moisture from the land, and rising temperatures can increase this evaporative demand. The lack of rain during a flash drought can further contribute to the feedback processes.

Under these conditions, crops and vegetation begin to die much more quickly than they do during typical long-term droughts.

In our study, we used climate models and data from the past 170 years to gauge the drought risks ahead under three scenarios for how quickly the world takes action to slow the pace of global warming.

Pasquale Mingarelli/Alamy Stock Photo

If greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles, power plants, and other human sources continue at a high rate, we found that cropland in much of North America and Europe would have a 49 and 53 percent annual chance of flash droughts, respectively, by the final decades of this century. Globally, the largest projected increases in flash droughts would be in Europe and the Amazon.

Slowing emissions can reduce the risk significantly, but we found flash droughts would still increase by about 6 percent worldwide under a low-emissions scenario.

We’ve lived through a number of flash drought events, and they’re not pleasant. People suffer. Farmers lose crops. Ranchers may have to sell off cattle. In 2022, a flash drought slowed barge traffic on the Mississippi River, which carries more than 90 percent of the United States’ agriculture exports.

If a flash drought occurs at a critical point in the growing season, it could devastate an entire crop.

Corn, for example, is most vulnerable during its flowering phase, which is called silking. That stage typically happens in the heat of summer. If a flash drought occurs then, it’s likely to have extreme consequences. However, a flash drought closer to harvest can actually help farmers, as they can get their equipment into the fields more easily.

Cropland in much of North America and Europe would have a 49 and 53 percent annual chance of flash droughts, respectively, by the final decades of this century.

In the southern Great Plains of the United States, winter wheat is at its highest risk during seeding, in September to October the year before the crop’s spring harvest. When we looked at flash droughts in that region during that fall seeding period, we found greatly reduced yields the following year.

Looking globally, paddy rice, a staple for more than half the global population, is at risk in northeast China and other parts of Asia. Other crops are at risk in Europe.

Ranches can also be hit hard by flash droughts. During a huge flash drought in 2012 in the central United States, cattle ran out of forage and water became scarcer. If rain doesn’t fall during the growing season for natural grasses, cattle don’t have food, and ranchers may have little choice but to sell off part of their herds. Again, timing is everything.

It’s not just agriculture. Energy and water supplies can be at risk, too. Europe’s intense summer drought in 2022 started as a flash drought that became a larger event as a heat wave settled in. Water levels fell so low in some rivers that power plants shut down because they couldn’t get water for cooling, compounding the region’s problems. Events like those are a window into what countries are already facing and could see more of in the future.

J. I. Christian et al., 2023

Not every flash drought will be as severe as what the United States and Europe saw in 2012 and 2022, but we’re concerned about what kinds of flash droughts may be ahead.

One way to help agriculture adapt to the rising risk is to improve forecasts for rainfall and temperature, which can help farmers as they make crucial decisions, such as whether they’ll plant or not.

When we talk with farmers and ranchers, they want to know what the weather will look like over the next one to six months. Meteorology is pretty adept at short-term forecasts that look out a couple of weeks, and at longer-term climate forecasts using computer models. But flash droughts evolve in a midrange window of time that is difficult to forecast.

We’re tackling the challenge of monitoring and improving the lead time and accuracy of forecasts for flash droughts, as are other scientists. For example, the U.S. Drought Monitor at the University of Nebraska- Lincoln has developed an experimental short-term map that can display developing flash droughts. As scientists learn more about the conditions that cause flash droughts and about their frequency and intensity, forecasts and monitoring tools will improve.

Thierry Monasse/Getty Images News

Increasing awareness can also help. If short-term forecasts show that an area is not likely to get its usual precipitation, that should immediately set off alarm bells. If forecasters are also seeing the potential for increased temperatures, that heightens the risk for a flash drought’s developing.

Nothing is getting easier for farmers and ranchers around the world as global temperatures continue to rise. Understanding the risk they could face from flash droughts will help them—and anyone concerned with water resources—manage yet another challenge of the future.

This article is adapted and expanded from one that appeared in The Conversation.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.