This Article From Issue

May-June 2003

Volume 91, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2003.44.0

Designing Sociable Robots. Cynthia L. Breazeal. xviii + 263 pp. The MIT Press, 2002. $49.95

In Designing Sociable Robots, Cynthia Breazeal shares her vision of a machine of the future that will be able to engage a person in many of the same ways that another human being can. The book documents a first step toward realizing this vision in the form of a humanoid robotic head named Kismet. While working on her doctorate at the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Breazeal designed and programmed Kismet in collaboration with other researchers, most notably Brian Scassellati (now at Yale University) and robotics guru Rodney A. Brooks. Kismet's hardware, software and performance in experiments are comprehensively explained and illustrated in the book and an accompanying CD-ROM, which includes video of the robot in action.

From Designing Sociable Robots

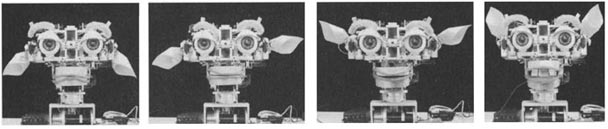

What exactly are sociable robots like Kismet supposed to do? They are designed to interact with people and to mimic human reactions as closely as possible while doing so. Kismet is an expressive humanoid head that is able to display a variety of emotions and, using both visual and auditory cues, to perceive people who are nearby. Compared with a typical person, Kismet has quite limited means to "socialize": On the perceptual side, it is restricted to recognizing and tracking different objects (such as human faces or toys) and detecting affective aspects of human speech directed at it. Based on these cues, it then uses its articulated face to express a variety of different emotions.

Kismet has turned out to be very successful at socializing with people who are willing to give it a chance. Note that, according to Breazeal, sociable robots actively seek to engage people: These robots are not just puppets that act when prompted; rather, they try to "lure" people into spending time with them by harnessing our natural social responses. Kismet shows, for example, a "sad" face when understimulated or "neglected," and people usually respond intuitively by making overtures. Such proactive behavior on Kismet's part is generated by an internal control system that includes the robot equivalent of human drives and emotions and is based on what researchers have learned about certain facets of human social intelligence. Not surprisingly, interactions between infants and caretakers were a major source of inspiration for Kismet's design.

Why is Kismet interesting? At first glance, the robot appears to be a cute, babylike toy, and on an emotional level most people respond to it accordingly. But cuter humanoid heads and robots can be found, and some mimic more closely the shape of a human face. (Kismet is a creative abstraction of a human face; its articulated ears actually give it a somewhat doglike appearance.) Also, researchers have been building and studying robots that interact socially with one another or with humans for years, and many computational models of drives, motivations and emotions have been developed for robots and other agents. Kismet wasn't the first robot able to interact with people, nor did it pioneer the use of "emotional" control architectures.

In my view, what makes Kismet unique is that it gets the dynamics right. When I first saw the robot a few years ago, its very nonrobotic, "natural" movements immediately caught my eye. I was also impressed that it used its expressive eyes, mouth and ears to regulate its interactions with humans. Unlike other "expressive robots" I have seen, Kismet does not use emotional expressions as "signals" that simply label a particular internal state of the robot. Rather, Kismet's emotional expressions are part of a highly complex and very dynamic regulatory feedback system that explicitly exploits the tendency of people to show appropriate social behavior toward the robot. Kismet's facial gestures and responses have a lifelike "smoothness"; they seem imbued with the fundamental rhythms that underlie the "dance of life" one sees in the interactions that go on between babies and caretakers and, perhaps somewhat less expressively, between adults. Kismet is far less mechanical in its movements than the Star Wars robot C-3PO, for example.

Such capabilities are astonishing to witness in a machine. But does that explain why we should care about sociable robots? Kismet is a special-purpose robot: Its only goal is to engage people. Its degree of sociability is somewhat limited. Kismet has some mechanisms of perception, adaptation and regulation of behavior that are prerequisites for social learning (for example, the robot can recognize expressive feedback and take turns), but it doesn't have social learning algorithms. Thus it cannot learn to distinguish between people or remember interaction histories, abilities that are fundamental to human social intelligence. Other future challenges include integrating principles of Kismet's design into a complete humanoid body and studying how to use emotional expressions while completing various tasks. Eventually sociable robots may have applications in a variety of areas from education to entertainment, so it makes sense to learn something about them now as they are being developed rather than wait for one to appear behind the customer-service counter.

And when might that happen? Sooner than you'd guess, if you believe Breazeal, who now directs the Robotic Life Group at MIT's Media Laboratory. I for one am looking forward to seeing how her vision will develop and manifest itself. In the robotics research community, Kismet has definitely left its mark, both as a milestone in the development of humanoid robots and as an example of a "benign," biologically inspired robot that is friendly and fun to hang out with.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.