This Article From Issue

May-June 2001

Volume 89, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2001.22.0

Creative Collaboration. Vera John-Steiner. xvi + 259 pp. Oxford University Press, 2000. $29.95.

The exploration of collaborations is presently a growth area in creativity studies—and deservedly so, since although there is a tendency to go it alone, and many think they do, on closer inspection it can often be seen that that is not the case. For example, Albert Einstein, once thought to have worked in isolation, had collaborators: In addition to his first wife, Mileva Maric (who, in my view, provided negative support—Einstein succeeded in spite of her), there were his loyal pals and, above all, the man he immortalized in the 1905 relativity paper, Michele Besso. In the often-quoted words of John Donne, "No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main."

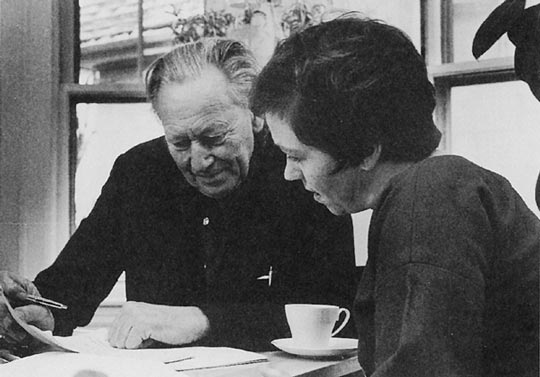

Photograph by Polyxane Cobb. From Creative Collaboration.

As studies of creative collaborations go, Vera John-Steiner's is a model of scholarship and deep understanding of the human psyche. Her message, illustrated by a plethora of case studies, is that deeply ingrained in us is the pioneering desire to go it alone, to tough it out—the cult of individual achievement. However, she writes, "When partners commit themselves to collaboration, they challenge these beliefs. The very effort to work together, to risk an undertaking that is so different from the norm, is a creative act."

The examples that John-Steiner uses to demonstrate this run the gamut from Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr, and Marie and Pierre Curie, to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller, Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. Included are instances of collaboration between men, between and among women, between lovers or husbands and wives, and across generations (between parents and children, for example). All permutations are taken into account, and John-Steiner draws important generalizations. Perhaps the most important is that the smallest indivisible unit is two people. This is the wellspring of creativity. However, she writes, "Intimate relationships demand delicate balances between interdependence and individuality, between a trust in one's own strength and the supporting power of connection."

John-Steiner illustrates this with case studies in which she delineates different mixtures of personalities, likes and dislikes, and preferences for working and living styles. For example, "disciplinary complementarity" refers in the main to scientific collaborations such as that between Marie and Pierre Curie, Marie being the doer and Pierre the thinker. It was the whole that produced the creative thrust.

Although the Curies were able to resolve the tensions that arise from lives that are totally entwined, this was not the case for every couple that John-Steiner describes, especially Plath and Hughes. When they met in Cambridge, where Plath was a Fulbright Fellow, she was already somewhat successful, whereas Hughes was essentially a rural poet. It was love at first sight. They drew the best out of each other. As mental illness began to play a destructive role in her life, he adjusted his life and working regimen to suit hers. But soon she became absolutely and neurotically dependent on him. A series of dramatic incidents led to him walking out, and she committed suicide soon after. John-Steiner offers the hypothesis that any collaboration or relationship by its very nature, especially when emotions are involved, becomes so intense that it runs the danger of exploding unless the partners are able to give each other "'space' when the need for solitude arises."

De Beauvoir and Sartre provide an excellent example of a pair taking this to the extreme. They never lived together, and although they were deeply emotionally involved with one another, by arrangement they often led separate love lives. At first this was to de Beauvoir's chagrin, but soon she gave in and used this freedom, as Sartre intended, to broaden her own horizons. In return Sartre said to her, "You did me a great service. You gave me confidence in myself that I shouldn't have had alone." This was reciprocal, and John-Steiner draws from this the important general conclusion that each participant's belief in the other's capability "is crucial in collaborative work."

Another interestingly developed example of a supportive relationship was the artistic and sexual liaison of Nin and Miller, depicted in the film Henry and June. Through her contacts in the high social circles in which she moved, Nin helped Miller, who was living on the margins of society in 1931, to publish The Tropic of Cancer. This, in addition to her encouragement, contributed to Miller's emergence as a self-confident writer. In turn Miller never ceased to praise Nin's encouragement, inspiration and active help. He painstakingly critiqued her own work, line by line, debating each idea, sometimes to the point of angering her.

These vignettes are but a meager sample of the far-reaching and novel case studies that John-Steiner explores and of the sweeping and important conclusions she draws. Her book is a must for creativity studies.—Arthur I. Miller, Science and Technology Studies, University College London

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.