This Article From Issue

July-August 2004

Volume 92, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/2004.48.0

For Love of Insects. Thomas Eisner. xiv + 448 pp. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003. $29.95.

In his introduction to Thomas Eisner's For Love of Insects, Edward O. Wilson calls Eisner "the modern Fabre"—an apt comparison, but one that may not mean much to modern readers, at least those outside entomology. Jean-Henri Fabre (1823–1915) was perhaps history's most acute observer of insect life, although he worked largely unrecognized until he was in his eighties. In 1907, the last of the 10 volumes of his Souvenirs Entomologiques appeared, and three years later, Fabre was lauded throughout France as a naturalist and as a literary stylist. For the last five years of his life, he enjoyed international fame, and dignitaries journeyed to his harmas (an untilled, pebbly expanse of land) in the small village of Sérignan to meet him.

Eisner brings the originality and practicality of Fabre to his own study of insects, but whereas Fabre epitomized the 19th-century tradition of the amateur naturalist, Eisner is a modern-day professional scientist. His work, unlike that of Fabre, is illuminated by a combination of evolutionary theory and technological innovation. Fabre's accounts of the lives of the insects he studied remain fascinating, if compartmentalized, stories. Eisner's work, summarized for the first time in this elegantly written and beautifully illustrated book, presents a coherent picture of a world little known even to many biologists.

During his graduate work at Harvard, Eisner formed a determination to combine his passion for insects and his interest in chemistry to "decipher the chemical language of insects." In 1955 he first encountered the bombardier beetles that were to catalyze a career-long theme: how insects use chemistry to cope with the challenges of their environment. In the course of many episodes of careful observation in nature and elaborate experimentation in the laboratory, Eisner and his major collaborators—his wife, Maria, and chemist Jerrold Meinwald—would found and develop the field of chemical ecology.

In this day of the nature documentary, Eisner does not share the obscurity Fabre so long endured. Eisner's work has been the subject of several television programs, in which the devoted entomologist is also seen as a genial and articulate spokesman for the scientific view of life. His sparkling lectures, complete with live demonstrations of the chemical armamentarium of arthropods, have delighted hundreds of students. And in this book, the reader almost gets the experience of a conversation with Eisner, as he leads us through a familiar, yet alien, country.

Eisner's way of working was established on that day in 1955 when he "felt the heat" of the bombardier beetle's discharge of its defensive chemicals. It is a process that begins with a walkabout in the woods, often the Florida scrub of his favorite field site, the Archbold Biological Station. Something odd, or something commonplace looked at in a new way, triggers a question. An experiment might be devised on the spot, and if the prospect pans out, the insect of interest is taken in numbers to the laboratory at Cornell, where the hammer and tongs of everything from high-speed cinematography to scanning electron microscopy and gas chromatography are applied. What results is usually a cascade of new questions that pull Eisner and his collaborators further and further into the world of an insect.

The book becomes a manual for discovery. In the chapter on the bombardier beetle, Eisner details how he worked out the chemistry of its weapon. Microthermocouples revealed that the spray leaves the beetle's rear end at a temperature of 100 degrees Celsius. Discovery by the team that the discharge is pulsed at 500 to 1,000 blasts per second led to a collaboration with Harold "Doc" Edgerton and the production of an almost incredible high-speed film showing the beetle's chemical machine gun in action.

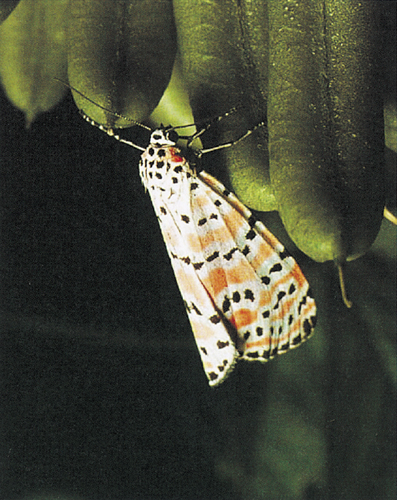

From For Love of Insects.

In the chapters that follow, Eisner introduces spiders that signal birds of their webs' presence, termites that harbor a chemical cannon in their heads and firefly females that lure—and then kill and eat—males of another genus of firefly by imitating the sexual signals of females of that genus. A fearsome-looking creature called a vinegaroon, or whipscorpion, spritzes predators with a blistering mixture of acetic and caprylic acids. Insect larvae disguise themselves with everything from their own feces to hairs gleaned from their host plants. A tiny millipede is its own tar baby, studded with hooked hairs that hopelessly entangle attacking ants. If defense and deception seem themes of these tales, it is because insects live in a terrifyingly dangerous world and use the tools at their command to survive and reproduce. The insight that many of these are chemicals is the "one big thing" in Eisner's research.

In the penultimate chapter, all the many threads of the book are drawn together in an extended account of Eisner's 30 years spent studying the moth Utetheisa ornatrix. This beautiful moth obtains a pyrrolizidine alkaloid from its host plant (any of various species of Crotalaria) and uses it as a defense against predators. The alkaloid also appears in the moth's eggs, contributed not only by the mother but also by the father, with the sperm package. Females lure males with a simple hydrocarbon pheromone and then assess their nuptial gift of alkaloid by their production of hydroxydanaidal, which may be derived from pyrrolizidine alkaloid. Eisner describes the elegant, simple experiments used to unravel the chemical web that links these moths to one another, to their host plant and to their predators. Nearly every insect he has investigated has a similar story to tell, and there must be thousands more.

The telling of entomological tales joins Eisner to Fabre once again. But Fabre, despite an extensive correspondence with Charles Darwin, never accepted natural selection and never linked his many observations into a theoretical framework. Eisner is a convinced Darwinian, and each of his chapters is another brick in an edifice supporting natural selection, joining the already numerous examples of that process in action, examples that make it possible for biologists to internalize the theory. Young naturalists who read this book will not only understand the scientific process, they will also absorb an intuitive understanding of evolution and how it works.

In this book-long conversation with Eisner, a few glimpses of the life paralleling the work slip out. He speaks briefly of his family's flight from Germany in the 1930s, his boyhood in Uruguay, his half-century of friendship with Ed Wilson and his love of music. Scattered among Fabre's Souvenirs are autobiographical essays that tell us much of the old Frenchman's character. I hope that before too much time passes, Eisner will write more about himself—his own story is likely as fascinating as any of those he tells in this book.—William A. Shear, Biology, Hampden-Sydney College, Virginia

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.