Empowering Success

By Marybeth Gasman, Thai-Huy Nguyen

Messages and examples of inherent inclusivity at historically Black colleges and universities set them apart from other institutions.

Messages and examples of inherent inclusivity at historically Black colleges and universities set them apart from other institutions.

Colleges and universities are often rewarded for being exclusive. Being competitive, climbing in the rankings, weeding people out of academic programs, and fighting over the “best” students is the norm on many college and university campuses. In contrast, most historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) focus on being inclusive—some even have an open enrollment policy—based on an inherent belief that all students can be successful.

Sabree Hill/Courtesy of Dillard University

Many predominantly white institutions give Black students the message that academic success is not in their future. This implicit bias is key to how racism works, conceiving of an individual’s potential based on the color of their skin or their cultural background. Racism excludes Black students from opportunities and spaces that many perceive as being beyond their intellect and capabilities—opportunities and spaces on which the majority places a premium, such as science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. Racism causes psychological harm to Black students, and in a culture of higher education that thrives on exclusivity as the definitive measure of success, sends a message that only a few can pursue and succeed in STEM occupations. In our study of 10 HBCUs (Dillard University, Xavier University of Louisiana, Prairie View A&M University, North Carolina Central University, Delaware State University, Morgan State University, Claflin University, Lincoln University, Cheyney University, and Huston-Tillotson University), we found that a belief in students’ ability to be successful was defined by a barrage of messages expressing inclusivity—nothing but the student’s own desires could or should hold a student back.

An institutional or departmental culture with a history of championing achievement can help students embrace and translate their own aspirations into earning a STEM degree. Assuming inherent success and seeing African American students as capable of success from day one of their STEM experience can make a fundamental difference in how they perceive the likelihood and trajectory of their achievement. In our campus visits to HBCUs, we heard some of the messages that faculty members share with students to engender their success, as well as the voices of students as they navigate a challenging academic terrain steeped in a deep and inclusive belief in their potential.

HBCUs have an extensive history of graduating successful African American leaders, educators, and innovators, a legacy that should be celebrated and heralded. Capitalizing on past successes of African Americans provides momentum for current students, especially those coming from environments where Black success is rarely recognized or celebrated.

“My professor brings in people like doctors, dentists, veterinarians that are already making it and doing what we want to do. He brings them in and they motivate us, tell us what we need to do, and they help us along. They’re also African American, so it helps, as some people don’t have that mindset that they can do whatever they want to do.”

Colleges and universities are in the business of recruiting, educating, and graduating students. A powerful way to attract, engage, and empower students is to promote the school’s history of achievement. Woven into and glorified by these narratives are famous writers and poets, scientists and their discoveries, and alumni who are leaders of industry. Overwhelmingly, the narratives of predominantly white institutions whitewash the past, ignore and dismiss histories of slavery and racism, and ignore the achievements of racial minorities and women. One of the most powerful aspects of HBCUs is the way they capitalize on their rich histories.

HBCUs have a legacy of graduating African Americans in science, and students regularly see highly successful individuals associated with the institutions. This history and track record of success is often championed in their classrooms. Not only do HBCUs build on the successes of their famous STEM alumni—such as surgeon and researcher Charles Drew, botanist George Washington Carver, physician and former U.S. Surgeon General Regina Benjamin, and physician and former U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Louis W. Sullivan—they build upon the great numbers of everyday alumni who are working as professors, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and researchers across the nation.

The hallways of Xavier University of Louisiana are lined with photos of their alumni and past institutional leaders, Black individuals who have overcome barriers to opportunity and achievement. These images are proof of a student’s own resilience and potential to achieve in an era in which racial discrimination and overt prejudices are illegal and considered morally wrong, but nonetheless continue to persist and affect students in pernicious ways.

Xavier University of Louisiana has a formidable history of producing doctors, which can be credited to Norman Francis, the school’s long-serving president who retired in 2015. In the 1970s Francis read a report that the number of Black doctors in the United States was dwindling at a steady pace. Francis was a man of action and decided to focus on turning Xavier University into a major institution for African Americans in STEM and, more specifically, Black doctors. As a result of consistent efforts over many decades, Xavier produces more Black graduates who apply to and graduate from medical school than any other college or university in the country.

From students’ points of view, attending Xavier gives them the confidence that they will succeed in becoming a doctor. They have few doubts about the future they wish to achieve. Xavier’s track record is well known among prospective students and is communicated with large billboards around the campus and throughout the surrounding states. Of its nearly 3,000 undergraduates in any year, 20 percent are pursuing degrees in chemistry, a subject critical for admission to medical and other health professional schools. Students know that success has come before them and that they will demonstrate success for future students. Felecia, a sophomore, shared her reasons for coming to Xavier:

I came to Xavier because I had a cousin who came, and then she told me how good they were with science programs, and that they were geared towards getting people into medical school. I just felt like for me it was the best option to get myself into medical school.

Students understand the history of Xavier and how this history will propel them to individual success. Another student, Dafina, explained:

One of the main driving points for me coming to Xavier was their success rate. Every time Xavier was mentioned, every time I say I go to Xavier University in Louisiana, people say, “Oh, you want to become a doctor!” because they just know that Xavier University breeds doctors, successful doctors, all over the country. Every time I’m studying, I say, “Okay, it’s been done before, I can do this, and I just have to keep going.”

Xavier’s reputation is profound, but the university is not unique in graduating large numbers of students who go on to be successful doctors. The difference is that Xavier primarily enrolls African Americans, and the institution bets on the potential success of these students. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, “medical school matriculants often come from middle and upper income families,” whereas a little over a third of Black medical students come from working class homes. In light of this national context, the odds are stacked against Black students seeking careers in medicine. And yet, despite having fewer resources than many predominantly white institutions, Xavier takes the risk of enrolling these students and succeeds in a way that fosters future success and hope in the minds of African Americans.

The supportive environment at Xavier University came from the top. Students told us that during orientation, the president communicated a message of success that ran counter to what their friends at other institutions heard:

President Francis spoke. And he said, “You know how most schools will say only 85 percent of you guys will graduate, everybody that you’re sitting next to won’t graduate?” He said, “No, we don’t say that here, everybody will graduate at the end of the four years.” So it’s like you don’t have a choice.

From the time they step onto campus, students are reminded of everyone’s potential to succeed. This message of success, however, is framed around inclusiveness—a significant contrast to predominantly white institutions’ implicit messages that Black students don’t belong in the college pipeline.

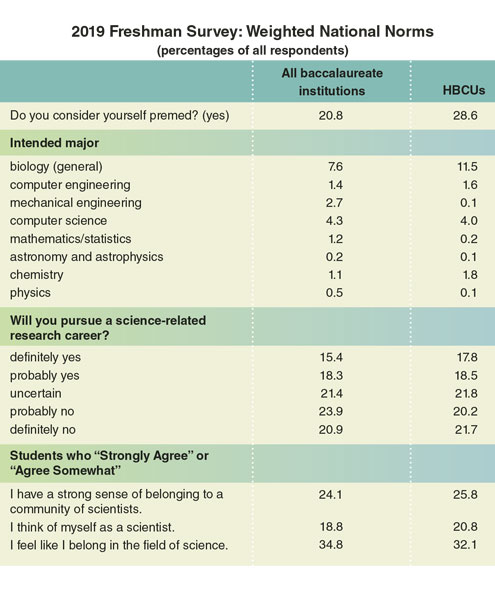

CIRP at UCLA, The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2019

Like Xavier University, Prairie View A&M University has a deep history of fostering success in medicine. Generations of their students have become doctors. One of the institution’s approaches to ensuring that students see themselves as successful is to bring former students—now successful alumni serving as doctors across the nation—back to campus at the beginning of the academic year and throughout students’ academic programs. Bernard, a student at Prairie View, told us that his professor ensures that students see success regularly and prominently:

He brings in people like doctors, dentists, veterinarians that are already making it and doing what we want to do. He brings them in and they motivate us, tell us what we need to do, and they help us along. They’re also African American, so it helps, as some people don’t have that mindset that they can do whatever they want to do.

Perhaps Prairie View biology professor Lynette Shaw says it best: “When you have a person who graduated from Prairie View and they come back and they tell you their journey, it makes a difference, and you can see that they are successful.” Seeing demonstrated success not only matters to students when they are in school but serves as an impetus for future and sustained success. It offers a glimpse into their own possibilities as well as their capacity to push forward.

“I’m going to do whatever it takes to get the students to reach the bar and cross the bar, and I’m not going to lower the bar. The culture is: We have to dig deep to unleash the greatness into our students. If that means working hard with them one-on-one, changing the way you develop your teaching strategies, do what it has to take.”

Most colleges and universities that have a record of success in STEM fail to realize how important it is for that record to include racial and ethnic diversity. This omission can result in a long-term, negative effect on African American students’ perceptions of belonging in a space that is dominated by white doctors. Even when established STEM programs achieve success among African Americans, they often fail to highlight this success or to keep in touch with graduates.

An institutional culture of success surrounds students with messages of empowerment that come from the president, faculty members, and student support staff. Feeling sure of having support is essential for students, especially for those who may not have received that quality of support from prior teachers. Thomas Owens, a Prairie View biology professor, stressed that he often believes in the capabilities and potential success of students more than they do themselves, because this is necessary when the messages students bring into college are damaging their confidence and limiting their view of their future. David, one of his students, confirmed Owens’s commitment:

I remember when I was drawing a molecule for the class, and he asked me if I thought that it was right. I was like, “Probably not.” He said, “No, it is. But I want you to know that it’s right.” He taught me that I need to be more confident with what I answer or whenever I’m taking a test, anything in general. I have to believe in myself and my abilities.

The care and attention demonstrated by Owens is life-changing for students because it pushes against a dominant false societal narrative of Black inferiority in STEM and the medical profession.

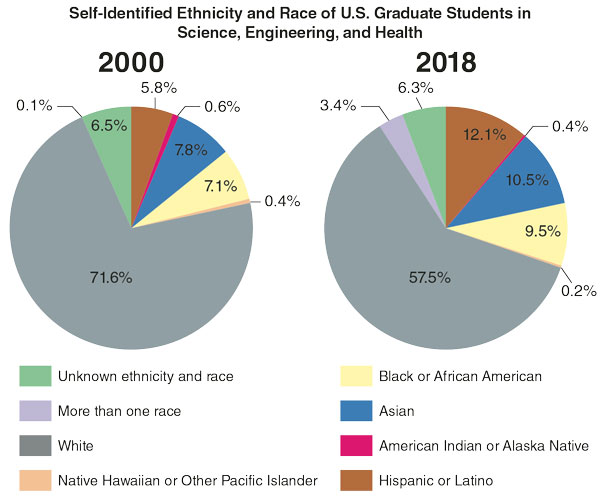

NSF Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering, Fall 2018

At Dillard University in New Orleans, the school culture of success is spearheaded by its president, Walter Kimbrough, who is dedicated to the superior performance of his students and to ensuring their success despite the odds against them. Kimbrough came to the presidency from a nontraditional path—as a vice president of student affairs—which gives him a special inclination toward students, about which he is quite vocal. Students know that their success is the centerpiece at Dillard and other HBCUs. Gina, a student at Dillard, told us:

At an HBCU, I feel like there are stronger values and morals around Black success. So, when African Americans come to these institutions, the main goal is to get you out successfully. It’s just to make sure that you’re here and we’re going to teach you what you need to know so that you can compete with any race or ethnicity that you’re put in the room with at any given time for any different career.

When students understand that their success is paramount to an institution, they feel empowered to succeed. Prairie View biology professor Bill Porter reported:

I’m going to do whatever it takes to get the students to reach the bar and cross the bar, and I’m not going to lower the bar. I tell my students, “Hey, an A student in my class should be an A student at Harvard or any other institution.” The culture is: We have to dig deep to unleash the greatness into our students. If that means working hard with them one-on-one, changing the way you develop your teaching strategies, do what it has to take.

Porter believes in students even when they might doubt themselves:

These kids have got so much promise in them, so much potential. But you’ve got to tap into it. And if you don’t tap into it, they don’t even know it’s there. You’ve got to let them know, “Hey, you might have been a C+ student in high school, but you know what? There’s greatness inside of you.” That’s what I think a lot of the faculty members do here. We can acknowledge or see a potential in our students, and we’ll pull it out and give them confidence. Once they know they can do it, they’re on fire and they take off.

Porter seeks students out and pushes them to be at the level of success he believes they have the unlimited potential to achieve. Often hearing his students joking with and yelling at each other in the hallways, Porter encourages students to use their voices in the classroom by noting their ample ability to use them outside of the classroom. He challenges students to bring all their confidence and words from the hallways into his classes, and presents learning as a way to demonstrate their strengths. One of his students shared with us Porter’s message, telling us, “When classes would get tough, because they do get tough, he would always be like, ‘You can do it. Believe in yourself.’” Students notice and appreciate his confidence in them.

At Xavier University students face a grueling curriculum that challenges them night and day. At the same time, they have access to teachers who champion their success. Students are encouraged to believe in themselves but are provided a safety net when the semester gets rough—a safety net that many first-generation and low-income students otherwise would not have. According to Ana, that safety net is the support of the faculty members who push her even when she is unsure of her own abilities and stamina for finishing: “Simply because of people who have been with me and that have pushed me, even when I was unsure of myself, they made sure I knew that, ‘You’re fully capable of doing that.’”

Quincy C. Moore

Black colleges in this study define success widely for students. When students do not achieve A’s in their classes, they are not dismissed as not being good enough to pursue PhDs and MDs. Instead they are counseled, pushed, and inspired by their faculty members. Their teachers work with them to create a road map for achieving higher performance in classes, rather than assuming students do not have the intellect or ability to conquer the coursework. Xavier University student Patrice told us, “I wasn’t supposed to be a tutor, because I got a B in organic chemistry for my second semester. But I guess my professor saw something in me that I didn’t see, and she [said], ‘No, you don’t have to have A’s in both chemistries, you can still do it if you have a B in one of them.’”

“It’s set up so you’re not going to fail. If you’re struggling, there are so many resources. Professors will email me, asking, ‘How are you doing? What should I change? Any suggestions?’ They’re very open and willing to help. They want to see you succeed. It’s not like you’re left to your own devices to learn everything and understand the material.”

What would happen if STEM faculty members at colleges and universities across the country took their focus off the highest-achieving students and placed more focus on those students at the next level, who are striving but need more support, advising, and input? Unfortunately, many faculty members tie their own worth to the success of their students, preferring to work with only the “top students”—many of whom are white and come from middle- or upper-class homes—and pay little attention to those students who need more work and are striving, or in some cases struggling, to succeed. Narrow definitions of promise and success not only exclude students from opportunities, they also operate to widen gaps in racial achievement.

Faculty members at HBCUs explained to us that students are fully aware that their teachers want them to be successful. Faculty expectations are high: “The students really know that we are watching them carefully and that we are invested in their success, so they don’t have an excuse. They can’t come up with an excuse.” Students understand the commitment of the institution and their department faculty members and use the commitment as a source of motivation. Felecia, a student at Xavier, puts it this way:

It’s set up so you’re not going to fail. If you’re struggling, there are so many resources. Professors will email me, asking, “How are you doing? What should I change? Any suggestions?” They’re very open and willing to help. They want to see you succeed. It’s not like you’re left to your own devices to learn everything and understand the material.

Faculty are proactive with students. Student success is prioritized in the design and delivery of curricula so that faculty members can coordinate with each other to anticipate student needs.

As the nation continues to ask questions about how to engender success among African American students in STEM, the answers are right in front of us and are rooted in a long history that begins with a belief in inclusive success. There is much to learn from HBCUs about cultivating a culture of success for African Americans across all colleges and universities and for students more broadly. Although the environment and culture of HBCUs cannot be replicated at other schools, the commitment to the success of students can be embraced. Predominantly white institutions can start by seeing all students as having value and by understanding the school’s role in students’ success.

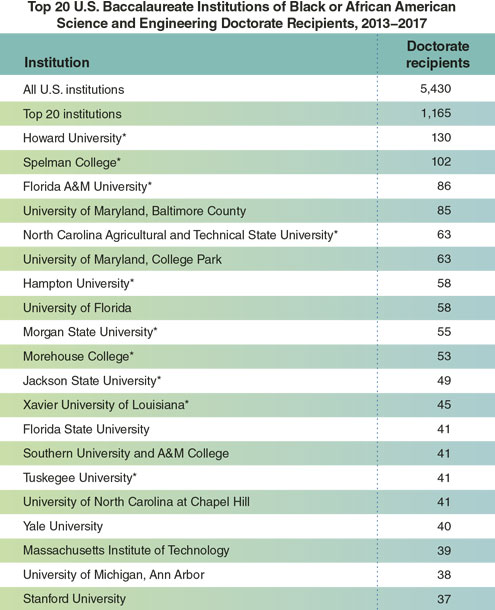

Barbara Aulicino/data from NSF

First, as with all priorities in the college and university context, a dedication to the success of African Americans in STEM must come from the top. Success must be at the forefront of the school president’s communications with faculty members and support staff. Leaders often speak about rigor and selectivity, not realizing that it would be more empowering, and would lead to wider success, to instead speak about inclusivity and how the institution can benefit students and support them. Bragging about who does not get admitted to an institution and boasting about selectivity only promotes competition, which can push out students who are unable to meet the school’s narrow metrics of achievement—which are based on narrow notions of college readiness and can make the less-prepared students feel unqualified to pursue a degree in STEM. Imagine if more institutions made an effort to identify the learning gaps that many African American students may have—based on their lack of access to a high-quality K–12 education, and not on their ability—and closed those gaps by creating environments that communicate inclusiveness and pathways to success for African American students. There is an enormous need for more STEM-educated graduates in the United States, and our colleges and universities could fill that need by promoting inclusivity and success for all students—placing students at the heart of schooling.

Second, the faculty members at the 10 HBCUs in this study demonstrate the effect of emphasizing African American student success from the time students step foot on campus and throughout their time in the classroom. Depending on one’s background and family access to a college education, a belief in oneself can be difficult to develop. Often the push or support of a faculty member against negative narratives that many Black students have internalized is what makes the difference between failure and accomplishment. Even African Americans who hail from middle-class, well-educated families face daily microaggressions that challenge their mere presence on college campuses.

HBCU faculty members teach us that success does not mean perfection. When African American students are not doing well in STEM classes, we must ask ourselves why and figure out what we are failing to do or provide. We need to realize that opportunities for success must be shared in equitable ways—not equal, but equitable, making up for past injustice. These HBCUs understand that not all their students enter with the same background and that therefore success must be measured in light of their personal circumstances.

This article is excerpted and adapted from the authors' book, Making Black Scientists: A Call to Action, published by Harvard University Press, 2019. The names of students and faculty members quoted in this article are pseudonyms.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.