This Article From Issue

May-June 2003

Volume 91, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2003.44.0

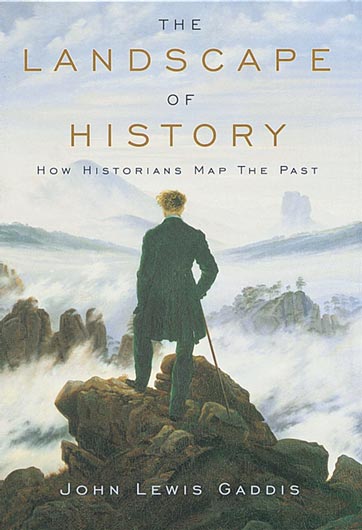

The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past. John Lewis Gaddis. xiv + 192 pp. Oxford University Press, 2002. $23.

John Lewis Gaddis sees the enterprise of history as the exploration of dimly known terrain. In The Landscape of History he contends that historians resemble scientists who study larger-than-laboratory-sized phenomena: They map the past in the way that paleontologists elaborate the evolution of life and astronomers chart the stars. In their marshaling of evidence, reliance on accumulated knowledge of many kinds, notion of causation, and enunciation of general laws, historians find common cause with those who study the natural world as it changes over time.

Gaddis agrees with the postmodernists that the grounds for evaluating human behavior are themselves artifacts of behavior, but he rejects their contention that words make the world. There are real things, and words mirror them. The length and shape of the British coastline depend on the scale and purpose of measurement, he notes, but this apparent relativity does not allow a supertanker to make for the cliffs of Dover and screw right through them. Here is a refreshingly plain-dealing methodologist.

In Gaddis's view, a temperamental antipathy distances historians from social scientists—the former are concerned with change over time, whereas the latter focus on a limited period and ignore historical antecedents. Historians generalize for particular purposes, embedding generalization in narratives, whereas social scientists particularize for general purposes, embedding narratives in generalization. Historians seek understanding in the texture of the past; their understanding is manifest in small assessments. Social scientists actively seek reasons for the landscape of history; to extend an analogy, they understand the rocks, rivers and forests in terms of the principles of geology, limnology and meteorology. Historians are, then, distinct and distinctive. Gaddis cites Jorge Luis Borges's tale in which a map of an empire eventually becomes as dysfunctionally detailed, and as large, as the empire itself. His point is that although historians often mistrust generalizations, they nonetheless generalize. He goes further by discounting empirical, reductionist psychologists and late 20th-century capitalist economists, who have not achieved their goal of predicting human behavior.

Despite his disaffection with the social sciences, Gaddis himself announces general propositions in the manner of a social scientist: Like the psychologist Hans Selye, he affirms that the individuals and societies best adapted for survival are the ones occasionally challenged from the outside. And like the sociologist Max Weber, he observes that the natural sciences exclude values, whereas the humanities and social sciences make them explicit; he also suggests that the end of history may lie in social criticism. Historians, he contends, are minor actors in establishing pernicious myths that animate oppression but are major actors in eliminating such falsehoods.

Gaddis finds inspiration in Marc Bloch and E. H. Carr, Marxist-oriented historians from the first part of the 20th century whose reflections on the craft are the stuff of methodology seminars. Bloch and Carr allow that the sciences can become objects of historical investigation. Gaddis disagrees—his faith in the hard sciences is intense, even idolatrous. He mentions Thomas Kuhn in passing, but his chief sources for science past are popularizers such as the late Stephen Jay Gould and physicist John Ziman. Gaddis, a specialist in the politics of nuclear war, gives barely a nod to historians of science as he comments on Albert Einstein, Werner Heisenberg, fractals, cloud chambers and dinosaurs. He confuses gravity with gravitation and appears unaware of the importance of laboratory experiments for paleontologists and astrophysicists.

The Landscape of History portrays science as immaculate conception—an enterprise removed from much of human activity. For Gaddis, as for Bloch and Carr, science connects with people in technology, an enterprise so distinct from science that some historians have identified each enterprise as an application of the other.

Historians have devoted much writing to the nature of the natural sciences and the humanities. Gaddis's broad thesis, a spontaneous reinvention of the habits of scholarship that unite both fields of inquiry, is supported by the connection between human history and natural history found in works by authors from Herodotus to E. O. Wilson. The very term natural history (tales of the nature we see around us) is a dead giveaway.

Whatever one thinks of Gaddis's arguments, his prose is abrupt, jangly and ambiguous. Consider the beginning of one section:

But patterns of oppression and liberation in history don’t just flow from what historians do to those who made it. For the past weighs so heavily upon the present and the future that these last two domains of time hardly have meaning apart from it. Whether they take the form of the language in which we think and speak, the institutions within which we function, the culture within which we exist, or even the physical landscape within which we move, the constraints history has imposed perfuse our lives, just as oxygen does our bodies.

Absence of parallel structure, pronouns lacking clear referents, dependent clauses threatening to hoist anchor or already floating derelict between subject and predicate—reading Gaddis is like standing in a moving subway car: One is continually on the lookout for a handgrip.

In the book's first and last chapters, Gaddis discusses Caspar David Friedrich's 1818 painting The Wanderer above the Sea of Clouds, which appears on the book's dust jacket. The representation, he says,

comes close to suggesting visually what historical consciousness is all about. . . . Elevation from, not immersion in, a distant landscape. The tension between significance and insignificance, the way you feel both large and small at the same time. The polarities of generalization and particularization, the gap between abstract and literal representation. But there’s something else here as well: a sense of curiosity mixed with awe mixed with a determination to find things out—to penetrate the fog, to distill experience, to depict reality—that is as much an artistic vision as a scientific sensibility.

Gaddis associates Friedrich's painting with the image of Gwyneth Paltrow's Viola wading ashore in the last scene of the film Shakespeare in Love, noting that both figures have "backsides so intriguingly turned toward us." Viola and the Wanderer could be contemplating the past—the landscape of history—but perhaps they're facing the future, observes Gaddis. "The fog, the mist, the unfathomability, could be much the same in either direction."

From The Landscape of History.

In dramatic contrast to the soggy Paltrow figure, the Wanderer is immaculately attired in the fashionable dress of a dandy—black frock coat, trousers and cane. No flies on him, no mire on his shoes. He has no pack. His wandering will be contemplative. In one sense, the painting is appropriate for Gaddis's theme: Gaddis's transcendental picture of science resembles Friedrich's romantic portrayal of nature's landscape. In another sense, the backsides are mooning Janus-faced history.

Scientists and historians are no strangers to metaphor and irony, but the study of nature and the writing of history both transcend ambiguity. Did Henry Cavendish weigh the Earth? Did the Spanish Armada go down in defeat? The detailed answers to these questions are clear and compelling. The narratives of both science and history are continually revised to take account of new discoveries. The firmest measure of progress in each domain is found in the trash bin of discarded propositions: It is highly unlikely that the civilized world will again place the Earth at the center of the universe. In the end Gaddis affirms that so very much depends on how both scientists and historians clarify the fog-enshrouded landscape before them.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.