This Article From Issue

November-December 2010

Volume 98, Number 6

Page 506

DOI: 10.1511/2010.87.506

A BETTER PENCIL: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution. Dennis Baron. xviii + 259 pp. Oxford University Press, 2009. $24.95.

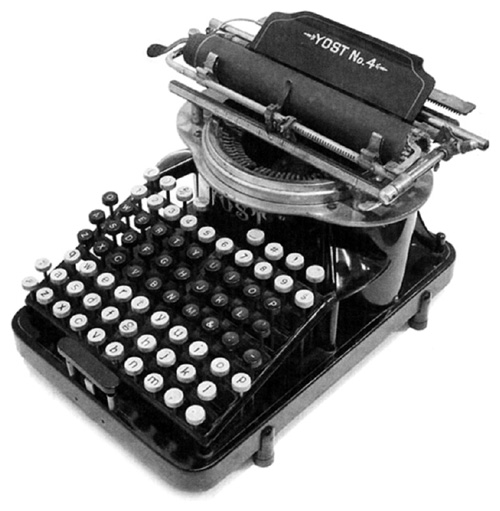

From A Better Pencil.

The world’s first technology for writing was invented not by poets or prophets or the chroniclers of kings; it came from bean counters. The Sumerian cuneiform script—made up of symbols incised on soft clay—grew out of a scheme for keeping accounts and inventories. Curiously, this story of borrowing arithmetical apparatus for literary purposes has been repeated in recent times. The prevailing modern instrument for writing—the computer—also began as (and remains) a device for number crunching.

Dennis Baron’s extended essay A Better Pencil looks back over the entire history of writing technologies (clay tablets, pens, pencils, typewriters), but the focus is on the recent transition to digital devices. His title implies a question. Is the computer really a better pencil? Will it lead to better writing? There is a faction that thinks otherwise:

These computerphobes are convinced that the machines will corrupt our writers, turn books into endangered species, and litter the landscape with self-publishing authors. In addition, computers will rot our brains, destroy family life, put an end to polite conversation, wreak havoc with the English language, invade our privacy, steal our identity, and expose us to predators waiting to pervert us or to sell us things that we don’t need.

Putting this bill of indictment in perspective, Baron points out that just about every other new writing instrument has also been seen as a threat to literacy and a corrupter of youth. The eraser had a particularly bad reputation, under the thesis that “if the technology makes error correction easy, students will make more errors.” I have to add that my own view of the computer as a writing instrument has always been that it’s not so much a better pencil as a better eraser, allowing me to fix my mistakes and change my mind incessantly, without ever rubbing a hole in the page. The first time I held down the delete key on an early IBM PC and watched whole sentences and paragraphs disappear, one character at a time, as if sucked through a straw—that was a vision of a better future for writers.

As Baron notes, those early computer writing tools were primitive and balky. The display screen looked nothing like ink on paper; fuzzy characters glowed against a dark background, like neon signs on a foggy night. Formatting was done by interpolating coded commands into the text, and the results of applying those commands appeared only when the document was printed. Baron himself had experience with even earlier and cruder tools, writing with a “line editor”—which, as the name suggests, allows you to make changes in just one line at a time—on a “dumb terminal” connected to a mainframe computer via an acoustic-coupled modem (the kind with rubber cups for the telephone handset). On balance, though, his response to this technology was favorable: “Working with line editors was painful, but once I tasted computer writing, I wasn’t eager to go back to a typewriter.”

What a long way we’ve come since the days of the line editor. Hardware and software for word processing have evolved to the point where the computer screen gives quite a good imitation of what words will look like on the printed page; if you wish, you can create documents on the screen that faithfully reproduce all the ornamental flourishes (and even the defects) of typefaces designed in the 18th century. And yet, now that we have finally attained this long-sought goal of ink-on-paper verisimilitude, the future prospects of paper itself seem a little tattered around the edges. Much text today is not only written on the screen but also read on the screen. Few Web pages, blogs, e-mail messages or Facebook updates are ever printed out, and newspapers, magazines and books are distributed online in editions designed to be read on computers or on more-specialized devices such as the Kindle. Virtual paper is displacing the real thing.

Will this shift in the technology of writing and reading be a positive development in human culture? Will it promote literacy, or impair it? Baron takes a moderate position on these questions. On the one hand, he acknowledges that the computer offers remarkable opportunities for self-expression and communication (at least for those of us in the wealthier parts of the world). Suddenly, we can all be published authors, and we all have access to the writings—or if nothing else the Twitterings—of millions of other authors. On the other hand, much of what these new channels of communication bring us is mere noise and distraction, and we may lose touch with more serious kinds of reading and writing. (Another recent book—The Shallows, by Nicholas Carr—argues this point strenuously.) Baron remarks: “That position incorrectly assumes that when we’re not online we throw ourselves into high-culture mode, reading Tolstoi spelled with an i and writing sestinas and villanelles instead of shopping lists.”

In the end, of course, the opinions of culture critics don’t count for much; for better or worse, the typewriter is not going to make a comeback, any more than cuneiform has a rosy future. I suppose the pencil may well remain a part of everyday life, and yet the time will come when the title of Baron’s book will seem antiquated and vaguely puzzling, like a reference to buggy whips.

As a matter of fact, certain passages of Baron’s book already seem frozen in a remote, sepia-toned era—way back in 2007 or 2008, when MySpace was the place to be, and the iPad was still a hot rumor. It’s a hazard of writing about a field where the pace of change outstrips the stately schedule of the book-publishing industry.

Brian Hayes is Senior Writer for American Scientist. He is the author most recently of Group Theory in the Bedroom, and Other Mathematical Diversions (Hill and Wang, 2008).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.