The Evolutionary Ecology of Escherichia coli

By Valeria Souza, Amanda Castillo, Luis Eguiarte

Abundantly studied and much feared, E. coli has more genomic plasticity than once believed and may have followed various routes to become a pathogen

Abundantly studied and much feared, E. coli has more genomic plasticity than once believed and may have followed various routes to become a pathogen

DOI: 10.1511/2002.27.332

Bacteria are full of surprises. Consider the most familiar and most studied of all cellular life forms: Escherichia coli. Although it has been subjected to scientific scrutiny for more than a century and has occupied center stage in the development of genetic-engineering technologies in the laboratory, E. coli continues to confound our ideas of how bacteria reproduce, adapt and colonize new niches.

In 1994, for example, Stephen Jay Gould wrote that "the most salient feature of life has been the stability of its bacterial mode from the beginning of the fossil record until today." Just eight years later, new insights into the nature of E. coli and its close relatives have made such a view of the bacterium as a stable organism seem superficial. Having now sequenced certain E. coli genomes and studied the population genetics of numerous bacterial species, we know that although the bacteria have undergone little change in morphology, their genome is a small but dynamic and changing entity that has not stopped evolving.

Recent advances in our understanding of the genetics and physiology of E. coli have in fact been spectacular. We know the entire genome sequences of three strains of this species, and the E. coli genome is undoubtedly the best understood of any genome (approximately 70 percent of its genes being "annotated," in the terminology of genomics). It has also been used as a model organism in evolutionary studies, both in natural populations and in the laboratory in so-called "experimental evolution" studies. These investigations have allowed us to understand better the action of two evolutionary forces, selection and mutation, over a very long time. These studies were based on the prevailing notion that these bacteria are clonal, passing genes from generation to generation with little scrambling or swapping—a notion that was entirely upset as the 20th century came to a close.

However, we have just begun to investigate bacterial ecology and evolutionary biology in natural populations. Such studies have gained urgency in connection with recent outbreaks of some pathogenic, foodborne strains of E. coli. These strains have virulence factors and genetic "pathogenicity islands" that have made E. coli, long a killer of infants in poor countries, a growing threat everywhere in the world. It is important to understand how this happens.

Our familiarity with E. coli comes from our intimate experience with it as well as its widespread use as a workhorse in the genetics laboratory. E. coli lives in the gut of human beings and of many other mammals, domestic and wild; it also lives elsewhere in nature. E. coli makes headlines when a pathogenic strain contaminates food or drink, but in fact there are many benign strains living unnoticed among our normal intestinal fauna and in our environment.

E. coli is a member of the Enterobacteriaceae family. Molecular phylogeny studies indicate that it is closely related to some other pathogens of vertebrates, including Shigella and Salmonella, the Vibrio cholera bacteria and Haemophilus, which can cause pneumonia and meningitis. The enterobacteria are characterized by their capacity for facultative respiration: They are aerobic in the open air but live anaerobically inside the gut. Thanks to this versatility, many members of this family are free-living, whereas others live in commensal relationships with animals or plants.

A harmless strain of E. coli called K-12, widely used in genetic-engineering experiments, has been well studied, and the genome of one variant has been sequenced by Frederick R. Blattner and his colleagues at the E. coli Genome Project at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This strain contains 4,639,221 base pairs, or 4.6 megabases, of double-stranded circular DNA (compared with the 3 billion base pairs of chromosomal DNA in the human genome). Of this genome 87.8 percent codes for proteins, and 0.8 percent codes for RNAs, or ribonucleic acids, key workers in protein synthesis. Another 0.7 percent consists of DNA without any known function. It is estimated that around 11 percent of the chromosome has regulatory functions. Some 28 percent of the 4,288 open reading frames (arrays coding for proteins) have no known function.

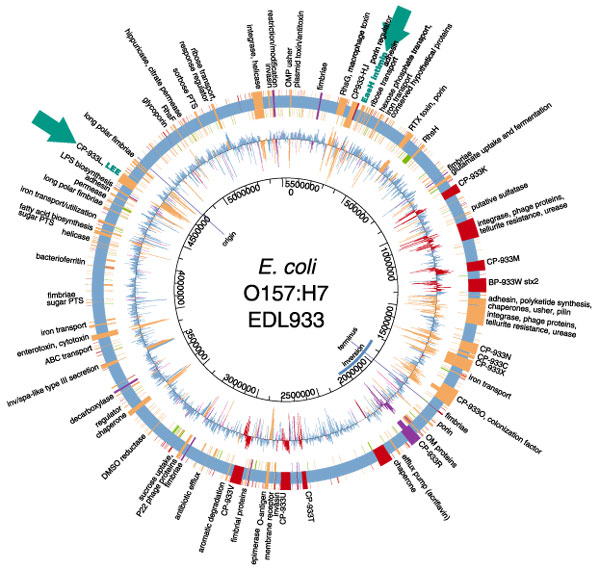

Other strains of E. coli may have differences in their genomic structure; it is now suspected that the maps are not always colinear and that the size of the genome varies from 4.4 to 5.5 megabases. The other strain that has been sequenced, a dangerous enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) known as O157:H7, appears to have acquired many of its genes by horizontal transfer since it diverged from K-12 about 4 million years ago. Horizontal or lateral gene transfer is a special talent of bacteria, which can exchange DNA within or across species lines. Such gene-swapping takes place through bacterial conjugation, when two bacteria join and share DNA; through the intervention of bacteriophages, or bacteria-infecting viruses; or through transformation, wherein they take up "loose" DNA from their environment.

O157:H7, the culprit in several recent fatal outbreaks of foodborne disease in the U.S. and Europe, turns out to have 1,387 genes that K-12 lacks; these include virulence factors, certain metabolic pathways and prophages (DNA acquired from viruses), as well as genes enabling DNA elements to move around on a chromosome. It is remarkable that a strain can have so many novel genes; these comprise some 25 percent of the O157:H7 genome. By comparison, all human beings are thought to be genetically about 99 percent identical.

When they released the O157:H7 sequence last year, Nicole T. Perna of Blattner's group at the University of Wisconsin and her colleagues noted that a comparison of the K-12 and O157:H7 genomes shows that the enterobacteria are the subjects of a great deal more genetic recombination, or scrambling of genes, than had been suspected. Lateral transfer creates bacterial genomes that are mosaics of genes with different evolutionary histories. For example, geneticists can find markers of inheritance by looking for patterns in the nucleotide bases that link to form double-stranded DNA. One common statistic is the proportion of base pairs that have the arrangement G-C, in which the bases guanine and cytosine are linked. The E. coli genome on average consists of 50.8 percent G-C pairs. But a number of important genes (15 percent of the K-12 genome and 26 percent of the O157:H7 genome) contain different G-C proportions from the rest of the genome and also use codons (triplets of bases coding for a single amino acid) in a very different way. For this reason it has been suggested that these genes came from other bacterial lines and were acquired by E. coli recently via horizontal transfer.

Jeffrey G. Lawrence of the University of Pittsburgh and Howard Ochman of the University of Arizona in Tucson in 1998 estimated the rate of these transfers to be at least in the range of 16 kilobases every million years; "pathogenic islands" (regions where genes that confer pathogenicity are found) dominate this activity.

Bacteria carry some of their genetic information in the form of extrachromosomal elements known as plasmids. These circular DNA molecules are the most dynamic component of the bacterial genome, since they move easily between strains. Plasmids are common in E. coli, although the bacterium can survive without a plasmid or, at the other extreme, store a good percentage of its genome in such elements. Around 300 kinds of plasmids have been described in the species. Within them one can find information for assimilating rare sugars and for producing colicins (substances that kill possible competitors of the same species); resistance to antibiotics and heavy metals; immunity against bacteria-targeting viruses and colicins; genes that code for genetic exchange; and filaments related to pathogenesis and the production of toxins.

Barbara Aulicino

In general the distribution of a plasmid depends not only on its range of bacterial hosts, but also on a complex system of incompatibility among plasmids of the same type. A bacterium will not accept new plasmids of a type that it already has. Although the movement of plasmids is not well understood from a molecular point of view, it is known that there are conjugative plasmids, which are capable of moving around by conjugation. These plasmids are relatively large (usually more than 50 kilobases) and contain genes necessary for bacterium-to-bacterium recognition; for forming the projections, or pili, needed for mating; and for allowing the movement of DNA. Nonconjugative plasmids also can be transferred when conjugation takes place.

Barbara Aulicino

Many plasmids are capable of transferring themselves among different species. Different models of plasmid distribution are possible in bacteria. Based on studies in 1997 of Salmonella and E. coli by E. Fidelma Boyd and Daniel Hartl of Harvard University, our laboratory has advanced a panmictic, or random-mating, model of plasmid distribution. Some plasmids are extremely successful and, being promiscuous as well, are overrepresented in bacterial populations. These epidemic plasmids allow bacteria to acquire virulence factors or resistance to antibiotics by horizontal transfer. Promiscuous plasmids can contribute to coevolution; as they move between bacterial species, the extrachromosomal genomes of those species may evolve in parallel. However, there are also clonal plasmids, plasmids that are only transferred from parent to child in asexual reproduction, as well as plasmids whose transfer is limited to specific genomes within the same bacterial species.

The great genomic plasticity of E. coli has conferred on it an extraordinary ecological plasticity. E. coli can adapt rapidly to different environments and is capable of existing as a free-living organism or in commensal mutualism in the colons of mammals and birds. Additionally, in the interior of host organisms, it can invade other niches successfully. In this way it can become a dangerous pathogen that successfully colonizes people and animals.

In spite of the abundance of bacteria, the study of their ecology is extraordinarily difficult and generally relies on indirect measurement. We believe the best way to understand bacterial ecology is through the use of genetic markers and the techniques of two fields: population genetics and molecular evolution.

Traditionally the colons of mammals and birds have been regarded as the natural habitat of E. coli. When E. coli causes illness, fecal contamination of food or water is commonly suspected; that is, health workers look for a way that E. coli from one mammalian colon could have gotten introduced into another's digestive system. It was long believed that the bacteria cannot reproduce on external media. However, recent results indicate that there are strains of E. coli that occupy niches other than the colon. Prominent among these are the pathogenic E. coli that can live in other parts of the digestive tract, in the blood, in the urogenital tract and in secondary environments. Strains found in drains and aquatic environments are in general more diverse than strains obtained directly from hosts.

A number of studies have found that aquatic and soil bacterial populations can increase their density over time, indicating that they grow and survive in these external environments. These studies suggest that E. coli infections can come from sources other than fecal contamination. But life for E. coli in a nutrient-poor environment such as water or mud is not the same as life in the rich environment of the mammalian gut. Bacteria in nutrient-poor environments divide at around 10 percent of the rate achieved in the laboratory.

Biologists know a number of things about the population ecology of E. coli that live in commensal relations with host animals. Generally there is one dominant strain of E. coli per host, but the appearance of new genotypes indicates that this dominance is temporary. Traditional evolution is at work here: The population can change through adaptive processes, in which a better strain displaces a less competitive one, or via the random processes known as genetic drift. The primary weapons of intraspecific competition are the colicins, which can destroy strains of the same species that do not display a plasmid coding for the same colicin. Colicins act by disrupting critical cellular functions such as the production of adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, the energy molecule central to cell metabolism.

E. coli is one of the first bacterial species to colonize mammals after birth; it is acquired from the birth canal and from the mother's feces. It has been calculated that the density of E. coli in the large intestine of mammals and birds is from 1 million to 10 million cells per gram of colon. This makes E. coli a minor component of the microbiota of this part of the intestine, which is primarily anaerobic, and has a total bacterial density calculated at some 100 billion cells per gram of colon. It is believed that in the intestine there is one cell division daily, whereas in the middle of a rich culture medium in the laboratory, E. coli K-12 can be seen to double six times a day or more.

In bacteria, reproduction is not tied to sexuality. Bacteria divide by binary fission to produce clones. Genetic variation comes about primarily by way of mutations passed along to clones. Horizontal transfer, which can be regarded as a parasexual process, serves as an additional source of variability in populations. In a population or species, the balance between these two processes is called the degree of clonality.

A highly clonal species is distinguished by a collection of independently evolved lineages. In these cases, it is difficult to speak of a species, since there is no pool of shared genes. It is much more difficult to apply classical population-genetics theory and concepts. Evolution is accomplished by substitutions of complete lineages, whether by selection or by genetic drift. If, however, bacterial species exhibit high levels of recombination, one obtains panmictic populations, and it is possible to apply approximately the same ideas about populations and species that we use with diploid organisms (organisms with double sets of chromosomes). Until the mid-1990s most evidence led scientists to describe E. coli as a clonal species, although its capability for gene transfer was well known.

The fundamental problem is that most bacteria exhibit a great number of possible mechanisms of recombination, but these are not used in every generation (that is, reproduction is uncoupled from sexuality). Also, it is hard to get direct estimates of the degree of sexuality of bacterial populations—the relative importance of processes other than fission. In order to study them one needs to use indirect methods derived from the theory of population genetics.

Classical studies of the genetic structure and clonality of E. coli revealed high levels of genetic variation within its populations; values of one common measure of variation reach from 0.47 to 0.52 on a scale of 0 (no variation) to 1 (each individual unique). But the number of multiloci genotypes, or complete genetic patterns, is small. In fact, initially it was estimated that the "linkage disequilibrium," a patterning of gene arrangements different from what random mixing of the gene pool (sexual reproduction) would produce, was around the maximum. This would indicate that few of all the possible genotypes were found, or that there was no recombination between strains. Studies completed from 1980 through 1992 almost without exception concluded that recombination is a rare phenomenon in E. coli asssociated with humans or domesticated animals and suggested (using population-genetics theory) that the effective size of the reproducing E. coli population was about 107 or 10 million genetically distinct organisms, a number relatively small in comparison to the expected total population of the organism, which has been estimated at 1020 or 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 cells. The effective population was sufficiently low to assure that random processes of the birth and death of strains were the dominant evolutionary force.

If there is little recombination, how does one explain the high genetic diversity we observe? Periodic selection could be one answer; a genotype might selectively displace others present in the population. In an asexual population, once a favored mutation spreads by natural selection, it replaces not just the gene involved, but a complete genotype. Such a story might make sense as a mechanism of adaptation to particular niches. In other words, E. coli would be, according to these ideas, a collection of very different strains, each adapted to a different environment.

The studies described above examined mostly strains associated with humans. Indeed, with E. coli implicated in a large portion of the more than 2 million annual deaths from diarrheal diseases, the human strains are understandably the focus of attention. However, this tight focus may have limited our understanding of evolutionary issues. For this reason our group initiated a long-term study of the evolutionary ecology of E. coli with a particular emphasis on populations in wild hosts. The first step was to organize a collection of strains from various continents (mainly from America, Australia and Antarctica) associated with wild mammals and birds, as well as environmental strains, including samples from the air, water and soil. This collection amounts to more than 5,000 strains. We call it IECOL, the Institute of Ecology Collection of E. coli.

In the first study we used 201 strains associated with mammals, in which we completed a population-genetics analysis using 12 polymorphic genes—genes whose alleles code for a number of different enzymes. In comparing these strains we studied the use of 12 sugars, resistance to five antibiotics, their serotypes, and the number and size of their plasmids. We found that the diversity is even higher than reported from human strains of E. coli (0.68 on the 0-to-1 variation scale). The genetic diversity is greater in Mexican than in Australian strains, and each group of host organisms displays a particular group of related strains. The Mexican mammalian strains are those that exhibit statistically the lowest linkage disequilibrium. Such a low level in a bacterial strain signals recombination and lateral transfer and suggests that the E. coli associated with mammals in general are not, on average, as clonal as was suggested by data from strains solely derived from humans.

It is interesting that in certain groups of strains, such as those associated with carnivores, rodents and primates, recombination is more frequent than it is in hosts with very specific diets. We have now estimated that the overall effective population size of E. coli is 5.3 x 109—that is, two orders of magnitude higher than that calculated for E. coli isolated from human hosts. Our estimate of the parameter of recombination is almost two orders of magnitude greater than the rate of mutation, again indicating that lateral transfer happens far more frequently than had been thought. Additionally, we found that the worldwide population of E. coli may not be homogeneous, but rather there may be isolated subpopulations. We draw this conclusion from the fact that the estimated global migration rate is less than the estimated migration within Mexico by roughly an order of magnitude. We have estimated the rate of recombination by comparing the congruence between the genealogies of different genes and those derived from analysis of various genetic loci, and we conclude that intragene and intergene recombination in E. coli is more important than mutation.

We have also conducted an analysis of the genetic sequences of four metabolic genes using 50 strains in the IECOL collection. These results were consistent with our emerging hypothesis: The genetic diversity from intergene and intragene recombination was greater in strains associated with animals than in those associated with humans. This difference is especially clear in the gene gapA, which appears to have suffered a reduction in its diversity after invading humanity.

Thus, our best sampling and the new, more detailed studies suggest that the basic biology of E. coli is far more complex and interesting than classical studies indicated. E. coli is endowed not only with a great genetic and ecological diversity, but also with a high level of genetic recombination and exchange. These phenomena permit the generation of a large quantity of genotypes, even though they may not occur in each generation. It is not only genes that move; there is considerable recombination of plasmids and fragments of genes. Some of these combinations turn out to be successful and invade many environmental niches and new hosts, and so continues the spread of new variants of E. coli able to become highly competitive—for example, O157:H7, first identified as a human pathogen in 1982. This generates a structure populated with ecotypes and at the same time produces strains that can live in a large number of environments that before were believed secondary or atypical for the species.

Recently, the study of mutation in microorganisms has taken on an interesting character. First there was the controversy over "directed mutation." Patterns of mutation were seen in bacteria that seemed less than random; were certain types of mutations favored over others? This debate, which began in 1989, was put to rest by studies whose results strongly contradicted this notion. But in 1996, a different question of mutation pattern surfaced when J. Eugene Leclerc and his colleagues at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration found that pathogenic bacteria such as O157:H7 are "hypermutable": They exhibit a much higher mutation rate than nonpathogens. According to Leclerc's proposition, errors in the DNA repair system may constitute a lifestyle adaptation that helps the bacteria escape the immune system of their hosts. The challenges of life as a pathogen may select for "mutators," variants that possess the ability to mutate rapidly during invasion, colonization and immune warfare. A year later, however, another study found the frequency of mutator strains to be similar between commensal and pathogenic E. coli in human beings.

The findings came in the midst of intense interest in the rise of antibiotic resistance. Resistance to antibiotic drugs appears to arise mainly through the sharing of resistance plasmids via conjugation. But high mutation rates might also play a role, and the idea continues to be hotly debated. Some studies of experimental evolution indicate that only under certain conditions can bacteria reach anomalously high mutation rates, especially in changing environments and small populations. Travis Kibota of Clark College and Michael Lynch of the University of Oregon presented in 1996 a model where hypermutability itself is always unstable, since there are more deleterious mutations than there are those that either carry pathogenicity, or are adaptive and provide escape from the host's attack.

Recently Antonio Oliver and his colleagues at INSALUD, Spain's National Institute of Health, studied patients with cystic fibrosis who were subjected at various ages to high doses of antibiotics to combat the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The P. aeruginosa of these patients displayed a significant number of hypermutations associated with gravely ill patients with other diseases. From this they proposed in 2000 that hypermutation is an adaptation that permits sufficient resistance to antibiotics for survival in the altered lung mucosa of a patient with this disease.

In E. coli we can compare evolutionary patterns between pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains by looking at pathogenic islands in the genome. Much work is being done to understand the evolution of a pathogenic island called the locus of enterocyte effacement, or LEE, which contains a group of genes that enable the bacterium to create lesions in the intestinal lining. We are currently conducting such comparisons by studying a part of the IECOL collection. There seems not to be any correlation between mutation rate and presence of the LEE or elements of this island, but we have begun to learn about other aspects of how bacteria acquire pathogenic abilities.

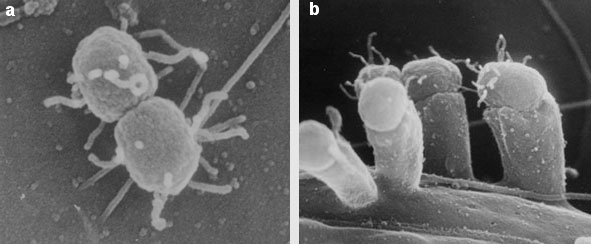

Two of the most dangerous types of E. coli are the EHEC, or enterohemorrhagic, strains such as O157:H7 often implicated in food poisoning, and the EPEC, or enteropathogenic, strains, which are an important cause of infantile diarrhea in the developing world. These strains can adhere to the wall of the intestine and rub off the epithelial villi, creating a lesion that disrupts the function of the intestinal wall and causes severe diarrhea that is often fatal, particularly in children and the elderly. The lesion is called an attachment-and-effacement lesion, abbreviated A/E.

Genetic and genomic studies have identified the genetic underpinnings of this process. The chromosomes of these E. coli (and of some other enteric pathogens, such as Shigella and Salmonella) include the LEE. In addition, they have a plasmid called EAF (for "EPEC adherence factor"). Within the LEE we find genes for a type III secretion system, a system used to deliver toxins and other proteins to an infected host cell. The cassette also includes signal-transduction proteins and a gene called eae, which codes for intimin, a protein that tightly binds the bacterium to the host cell. The LEE package also includes tir, a gene coding for the intimin receptor Tir; genes for some secreted proteins (espA, espD, espB); and the regulator Ler. In the EAF plasmid there is a group of genes called bfp, responsible for producing a filament to attach the bacteria to the host cells, and the regulator Per, which controls the expression of the LEE genes through interaction with the chromosomal regulator Ler.

Within the past year the relations of various genes associated with the A/E lesion have been mapped in our laboratory with a branching diagram, or dendrogram, obtained by examining 155 Mexican strains. The genes cesT/eae and espB can be found together, forming part of the LEE, or existing independently in the strains of healthy animals. These genes appear to have other roles in addition to pathogenesis, since the gene espB predominates in animals with specialized diets, such as the ungulates, manatees, whales and bats. In contrast, the gene cesT/eae is most frequent in strains associated with rabbits, armadillos and anteaters. Both independent genes are found distributed throughout the dendrogram.

This suggests that cesT/eae and espB are ancient genes in E. coli, and that they have a role in the normal, nonpathogenic association with their host. In a sequence analysis of 50 strains that do and do not possess the LEE, we found that the genes eae and tir are the most variable in their sequences, and that the gene espB is less variable. There is an association between the types of sequences in eae and tir, although this is not clear with espB. From the same sample of the collection we also sequenced five genes outside the island (gapA, fimA, mdh, muts and putP). Additional statistical analysis suggests that pathogenic and nonpathogenic genes have different types of selection acting on them. Some genes show diversifying selection (an increase of diversity to escape the host response), whereas others show low levels of diversity owing to purifying selection (low diversity being selected in order to conserve a specific function). More interesting, LEE genes are almost twice as diverse as nonpathogenic genes, and they have very different substitution rates.

In 2000 Sean D. Reid and his colleagues at Pennsylvania State University proposed that pathogenic islands including the LEE are evolutionary units whose genes have integrated at the same time and evolved coordinately. If this is true, the origin of new pathogens could be explained by successive events of horizontal transfer, for example from EPEC to EHEC. But when we compared the genealogies for individual genes, we were surprised to see that each has a very different history to tell. In evolutionary terms, the LEE appears to be not a unit but rather a dynamic assemblage of genes that act together to make a lesion.

On the other hand, the plasmid genes per and bfp have never been detected in the strains associated with wild animals and are found only in EPEC and EHEC strains associated with human patients. This is evidence that horizontal-transfer events are important in the history of plasmid-carried pathogenesis.

It seems that the origin of new pathogens is a complex phenomenon produced by the dynamic between the chromosomal component (LEE, for example) and the plasmids within the bacterial populations. From these results we conclude that the evolution and emergence of new pathogens is still not well understood. We need to combine more work on population genetics, population ecology and molecular evolution in order to have a wider view and a better idea of the dynamics of E. coli natural populations; this is the only way to understand the evolutionary biology of this organism.

In spite of the fact that E. coli is the best-known bacterium in the world, we are just starting to understand its ecology and evolutionary biology. It is clear that E. coli is a very diverse bacterium and that its genome is highly dynamic. It is not the strictly clonal organism suggested in the first population-genetics studies. It is a bacterium with a generous and complex sexuality, which has played a role in, among other things, its success as a pathogen. Successful combinations can be dispersed in epidemic fashion in human or animal populations, giving a false signal of clonality.

The diverse tools of molecular genetics and population genetics offer the possibility of completing adequate ecological and evolutionary studies of bacterial populations. These studies should be based on a solid knowledge of natural populations, their ecology and their biology. In our studies with the IECOL collection we have tried to make advances in this direction in E. coli. We are pleased to place our collection at the disposal of persons interested in working with it, and we look forward to the continuing evolution of our understanding of E. coli.

The authors thank Aldo Valera, Laura Espinosa and Andy Peek for technical assistance; Becky Gaut for lots of ideas; Martha Rocha, Luisa Sandner and Claudia Silva for interesting data and endless discussions; and Alejandro Cravioto for showing them the fascinating world of the enteropathogens. This project was supported by CONACyT grants 27557-M, and 0028 and DGAPA grants IN-218698 and IN-208601.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.