Drawn to Caribou

By Bethann G. Merkle

In Canada’s Northwest Territories, an ecologist is replacing lab notes with sketches that blend genetic research with traditional ecological knowledge.

In Canada’s Northwest Territories, an ecologist is replacing lab notes with sketches that blend genetic research with traditional ecological knowledge.

DOI: 10.1511/2016.118.16

When Jean Polfus submitted her PhD proposal to determine the genetic relationships and population distribution of three subspecies of caribou in the Northwest Territories of Canada, artwork was not part of her plan. Somewhat to her surprise, however, just over a year into the project, she found herself developing visual aids that would bring together caribou genetics, sociology, language preservation efforts, and traditional hunting practices.

Photograph by Jean Polfus.

Polfus’s work aims at synthesizing traditional ecological knowledge and contemporary scientific methodologies. Her master’s project built on experience with hardwood forest ecology and caribou population management, by blending habitat modeling and ecological knowledge in British Columbia’s Taku River Tlingit First Nation. Her fascination with this mixture of modern science and traditional knowledge then led her to the Northwest Territories. For the past four years, she has been researching caribou genetics in the Sahtú territory of the Dene First Nation. This land is rich with hunting grounds, in a a region where isolated modern villages cling to three dialects of a staggeringly complex language at risk of extinction.

Working with the Dene presents Polfus with a tangle of sociopolitical and environmental tensions as well as with tremendous creative opportunity. She faces challenges that are rooted in cross-cultural social skills, language barriers, and a history of forced assimilation and disenfranchisement that makes itself heard in native voices at every community meeting she convenes and every time she consults with Dene elders.

Photograph by Jean Polfus.

An underlying purpose of Polfus’s efforts is to help preserve the ecological knowledge that has sustained the Dene Nation for centuries. To do that, she says, “One major possibility we‘ve overlooked is to go directly to the people and their languages, which have evolved together with this diversity.” For comparing traditional ecological knowledge with genetics, caribou are an ideal test case, says Polfus. They’re particularly suitable because—unlike moose, which look much the same wherever they are found—caribou exhibit great morphological variation throughout their circumpolar Arctic habitat. The Sahtú territory is home to three subspecies, each named (in English) for its preferred environment: boreal woodland, barren-ground, and mountain woodland caribou.

Polfus’s work carries on a tradition exemplified by renowned ecologist and artist Jonathan Kingdon. Not content to be a mere observer in the field of comparative morphology, Kingdon set himself the formidable task of studying African fauna by illustrating it (for example, East African Mammals, 1988; Mammals of Africa, 2013). Reflecting back on his career, he said, “I have slowly come to realize that the analytic, quantitative approach I had been taught to regard as the only respectable one for a scientist is insufficient.”

Polfus’s work bears out this insight. Fortunately, in addition to the analytical approach of a scientist, she has the cross-disciplinary training that comes from combining an undergraduate minor in fine arts with an advanced degree in ecology. In order to overcome the language barrier she encountered when she began to enlist the help of the Dene hunters, Polfus resorted to sketching pictures of the appropriate methods for collecting data; the hunters then used her sketches as a guide for collecting samples of caribou scat. The mucus on these samples yields the DNA on which she is conducting her genetic research.

In relying on illustrations to convey meaning, Polfus’s approach echoes that of eminent botanist and biological philosopher Agnes Arber, who, with training from her artistic father, illustrated several major books on botany and biological philosophy in the first half of the 20th century. Arber insisted that drawings were equal to words in their power to communicate about science. Pairing her images with familiar terms, Polfus uses family blood lines to explain the concept of genetic relationships to Dene audiences. This combination has enabled her to effectively engage with Dene community members who have the potential to make significant contributions to her work as citizen scientists.

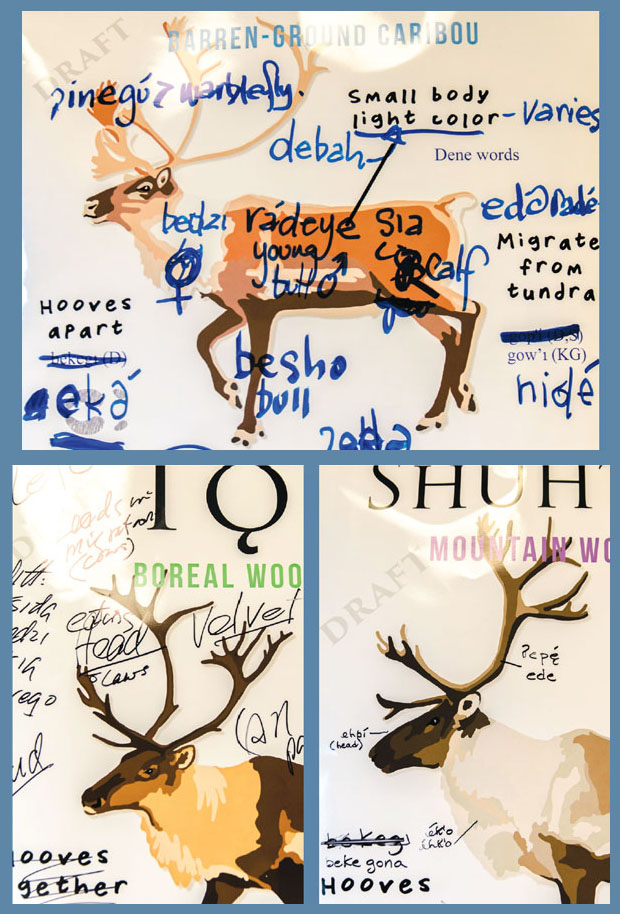

Polfus’s underlying focus is to enhance scientific understanding of caribou biodiversity. To foster the necessary closeness for collaborating with Dene elders, Polfus is currently living in a Dene community. Her work there catalogs the morphological and behavioral features of the three subspecies of caribou that inhabit the region. In particular, she is focused on the features that enable the Dene to distinguish among the three subspecies. As Polfus notes, the Dene are intimately familiar with the differences between barren-ground caribou and their boreal woodland conspecifics, and between both these groups and the mountain woodland caribou, but their knowledge has never been scientifically documented. Instead, from the perspective of Western science, caribou biodiversity is assessed as an amalgam of several factors: ecotypes (or specific behavioral adaptations), morphology, and genetics. Polfus points out, however, that none of these conceptual frameworks is a perfect fit—all three “continue to be challenged, adapted, and refined as more information becomes available.”

Likewise, from a Western scientific perspective, detailed note-taking and objective photography may seem the most obvious ways to capture this knowledge. As tools for conveying the ecological and sociological complexities of the Dene world, however, they are insufficient. Here, the eyes and hands of an attentive observer may prove invaluable; a detailed drawing or even a quick sketch can distill the information contained in any number of photographs. Indeed, according to Kingdon, “Drawing can be employed as a wordless questioning of form; the pencil seeks to extract from the complex whole some limited coherent pattern that our eyes and minds can grasp. The probing pencil is like the dissecting scalpel, seeking to expose relevant structures that may not be immediately obvious and are certainly hidden from the shadowy world of the camera lens.”

With her pencil and digital drawing tablet, on her own and in meetings with Dene elders, Polfus probes both to understand caribou morphology and to communicate it. She eschews the camera for this work because, in her words, “photography shows everything,” and this mass of information can be overwhelming. “If you want people to learn about different types of caribou, the drawing simplifies the information,” she says. The executive director of the Sahtú Renewable Resources Board, Deborah Simmons, concurs. Herself a Sahtú (though non-Dene) native, Simmons says, “In the Sahtú region, visual representations are a way of bridging cultures and transcending language barriers.” With three dialects still current in this sparsely populated territory, Simmons points out, “We English speakers have to wrestle with the difficulty of fully comprehending Dene concepts that arise from their experiences, their language, and their culture.”

In Dene, the different words for the three subspecies of caribou are not a matter of arbitrary distinctions. In the ecological framework of the territory these are, in effect, three different animals, and the Dene use a different hunting technique for each. Polfus explains: “Boreal woodland caribou are known to be wary of people and are rarely found in the open; hunters will pursue these animals only if they find extremely fresh tracks. Barren-ground caribou are known to spend more time in the open, on the edge of frozen lakes or marshes. They do not have as strong a flight response as the boreal woodland caribou because they stay together in large herds, which hunters can more easily approach. Historically, the Dene people have used systems of fences and barriers to force barren-ground caribou herds into snares and tight openings, where hunters waited with spears and arrows.” By contrast, when hunting the mountain woodland caribou, the Dene have traditionally gone to certain salt licks at the bottom of valleys, where caribous and other animals like to gather. With different names for the three subspecies, the Dene language preserves several layers of knowledge about each one.

Illustration by Barbara Aulicino.

The Dene language places a premium on the relationships among various animals or people or things. Elders often highlight the importance of their relationship with animals through stories of a distant past: for example, “Dene used to be caribou at one time.” This frame of reference reminds Polfus of her own academic pursuit. “This is how ecology tries to understand things—we look at connections and relationships,” she says.

It is possible Polfus would never have discovered this traditional-ecological coherence had she relied solely on genetic samples gathered from caribou scat. Delving into the Dene language has enriched her perspective and compelled her to illustrate what she and her Dene sources are describing together. Conversely, although the language has preserved indigenous knowledge about caribou diversity, the language alone is not enough to pass that knowledge on. Today it must be presented and taught explicitly to the youngest of the Dene Nation—if not at home or on hunting trips, then in a more formal setting.

To help address this challenge, Polfusis producing posters featuring her illustrations, refined and annotated by Dene elders. The posters will be distributed to schools throughout the region, in order to provide a modern yet authentic opportunity for young people to learn about the morphological distinctions that fascinate ecologists and still provision the Dene elders.

Polfus’s illustrations also embellish a book, Remember the Promise, developed by the Sahtú Renewable Resources Board to integrate traditional Dene knowledge into the planning of legislation concerning species at risk. As described on the board’s website, the book tells of “ancient times when wildlife were giants and made their own laws” and describes how “Dene and other living things agreed to live together and take care of each other.”

Sketches by Jean Polfus.

Polfus’s meticulously prepared drawings demonstrate the truth of biologist E. O. Wilson’s claim that “the description of species and the study of biodiversity, including the study of endangered species, requires hand-wrought illustrations.” The text of the book is trilingual, in two of the Dene dialects as well as English. As Michael Neyelle, a native Dene speaker and language expert, writes in the foreword, “Keeping the Dene language alive is part of keeping alive people’s sacred and respectful relationships with other living things.” Deep in the Northwest Territories’s Sahtú region, Polfus and her collaborators are establishing novel synergies, demonstrating the type of innovation that is possible only when science and art are mutually engaged.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.