This Article From Issue

March-April 2018

Volume 106, Number 2

Page 123

Determining the origins of prehistoric cave markings is a complicated endeavor, as Paleolithic art specialist Michel Lorblanchet and archaeologist Paul Bahn explain in their recent book, The First Artists: In Search of the World’s Oldest Art (Thames and Hudson, 2017). In caves that have been occupied at various times by humans and other mammals, it can be especially challenging to distinguish bear claw marks from traces of Paleolithic engravings. Investigations that are too rushed or may be strongly influenced by theoretical views of prehistoric art can complicate the evaluation process. To prevent misinterpretations, as the authors suggest in the following passage from their book, it’s best for researchers to be thorough and follow the data.

The comparison and distinction of engravings and animal claw marks are necessary in all studies of parietal art; they pose some interesting and sometimes difficult problems to specialists in exactly the same way as marks on bones and stones. Just like humans, the animals that frequented caves (bears, felines and hyenas, and small creatures like foxes, badgers and rabbits) left traces of their presence in every period. On the same walls that were painted or engraved by humans, the cave bears who intensively frequented the deep caves in which they hibernated also polished the lower surfaces through their repeated passages, and left a variety of traces on the ground: their “nests,” paw prints, feces and marks of sliding, for example. Some of these traces can even be considered ursine “drawings” when there are innumerable claw marks, or intentional blows from claws that declare a presence and define a territory.

When studies of the subterranean world have been too rapid and superficial, prehistorians have sometimes confused bear claw marks with engravings, especially when these claw marks were produced on a fairly hard rock such as limestone or calcite, because on a support of that type animal claws can leave a narrow, shallow groove that may resemble an incision by a flint. On softer clay surfaces, bears left deep lacerations, and in such cases their spectacular claw marks leave no doubt about their animal origin.

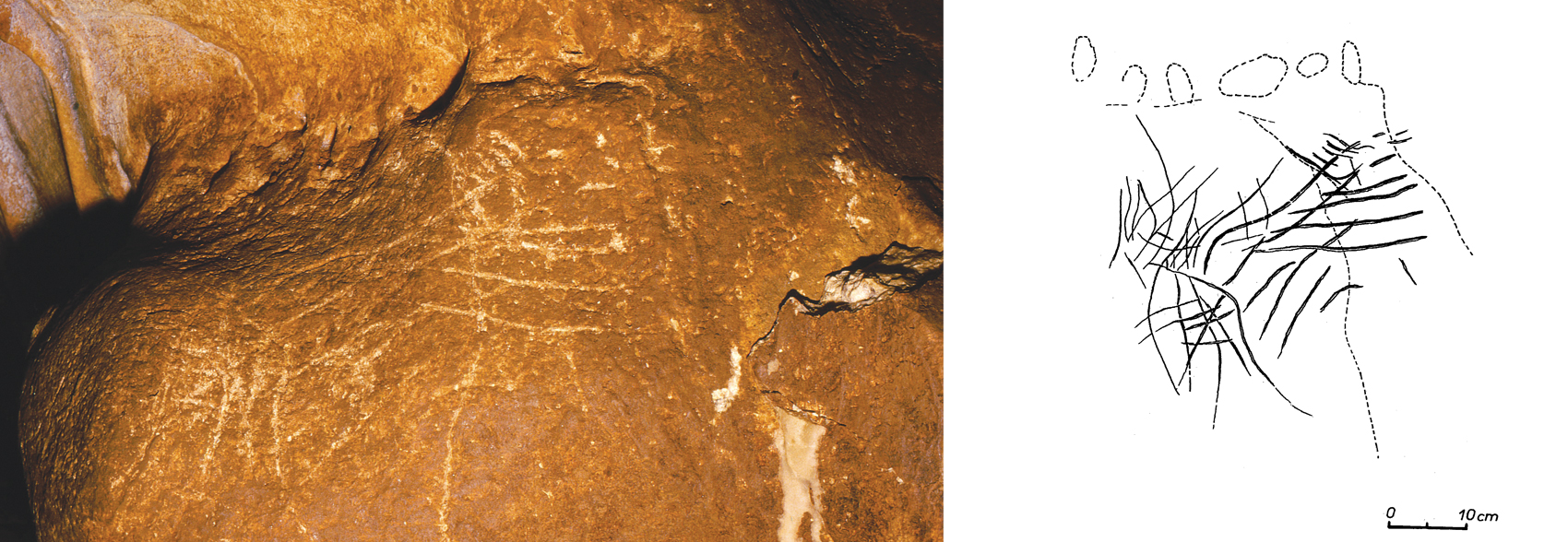

Photo and field diagram courtesy of Michel Lorblanchet. From The First Artists.

One example of confusion between claw marks and engravings can be seen in the interpretation that several prehistorians have given of the bear claw marks in the Combel gallery in Pech-Merle. In the deep part of this gallery a massive concretion is covered in all directions by claw marks that crisscross and cover a good deal of the surface. In 1961, Amédée Lemozi announced that these lines were Paleolithic engravings, and thought he could see a “masked and wounded human figure”: “It is possible to see in this type of figure, pierced by lines, an initiation scene during which the initiates or future shamans have to die a ritual death or as an effigy, a prelude to a new, transcendent life. The pecking and the lines seen on this character doubtless represent wounds.”

As a faithful follower of Romanian historian and philosopher Mircea Eliade, Lomozi extrapolated his readings onto the object of his study, and was already afflicted by the first wave of shamanism (of which the apogee was the Abbé Glory’s “Ongones theory” in 1964; the second wave, so powerful in the media, arrived more recently from South Africa). The “wounded” and/or “masked” man of the Combel then continued his progress through the prehistoric literature. He was to reappear in 1984 in a work by Lya Dams that provided an overview of “wounded men” in Paleolithic and Spanish Levantine art, but this time he was endowed with a sex that seemed to confirm that this was indeed a “shaman” and not a “shamaness”!

Some traces can be considered ursine “drawings” when innumerable claw marks or intentional claw blows declare a presence and define a territory.

In 1989 the recording by one of us (ML) showed that this figure is a pure figment of the imagination: In reality it is made up of an assemblage of cave bear claw marks in the calcite, which was softer than limestone; those with experience of the subterranean world, such as prehistorians who regularly undertake parietal recordings, know that bears sometimes produce gashes in all directions, and up to several meters in height, including horizontal claw marks. The “wounded man” of the Combel illustrates, once again, the dangers of the imagination in the study of Paleolithic art.

Elsewhere, in the cave of Les Battuts (Tarn, France), two prehistorians (Edmée Ladier and Anne-Catherine Welté) and a speleologist (Jacques Sabatier) thought they had detected some parietal engravings evoking Magdalenian tectiforms, but they rapidly came to realize that these were cave bear claw marks; they too called attention to the “claw marks/engravings ambiguity” and the risks of confusion that this brings. Only complete knowledge of all the natural and anthropic phenomena on the walls of a cave can make it possible to identify a parietal motif with any certainty.

From The First Artists: In Search of the World’s Oldest Art, by Michel Lorblanchet and Paul Bahn. © 2017 Thames and Hudson Ltd, London. Reprinted by permission of Thames and Hudson Inc, www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.