This Article From Issue

March-April 2013

Volume 101, Number 2

Page 146

DOI: 10.1511/2013.101.146

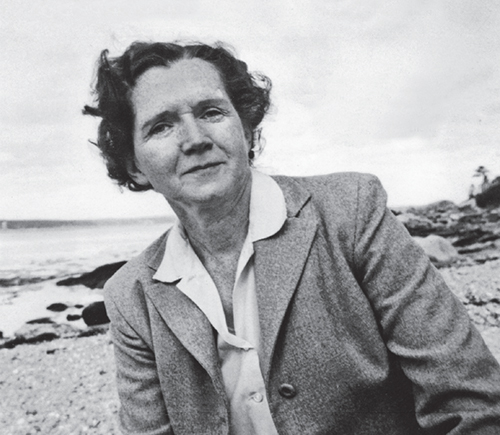

ON A FARTHER SHORE: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson. William Souder. xii + 496 pp. Crown Publishers, 2012. $30.

From On a Farther Shore.

As we seek to orient ourselves within the world, the question of how scientific evidence might help us do so has historically been a vexed one. In 1861, for example, amid partisan controversies over Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, economist Henry Fawcett publicly defended its scientific integrity. That integrity was sound, although others chose to interpret the book’s meaning differently in relation to religion and other perspectives. In a letter of thanks to Fawcett, Darwin wrote: “How odd it is that anyone should not see that all observation must be made for or against some view if it is to be of any service.” More recently, a 2012 report by the Union of Concerned Scientists criticized News Corporation, one of the world’s largest media companies, for misleading the public about the integrity of scientific evidence for anthropogenic climate change by conflating conflicts about facts with what are often, instead, clashes between worldviews.

On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson, William Souder’s deeply studied, well-written biography of Rachel Carson (1907–1964), helps us see her life work as crafting a narrative in which science is used to care for Earth, a narrative that eventually came into conflict with one in which science is used to dominate Earth. Carson understood herself foremost as a writer. As an undergraduate she discovered that biology gave her “something to write about” and that her work would be entwined with the sea. After performing a research stint at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and earning a master’s degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins in 1932, she wrote about Atlantic Coast fishes for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. One of her assignments, “Undersea,” was published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1937, launching her literary career. She was an ambitious, demanding author; in 1952, Souder relates, she wrote to her editor Paul Brooks at Houghton Mifflin, “reminding Brooks that they had agreed she was to be ‘free to develop the book in what seems to be my own peculiar style.’” Employing that style, she wrote four bestsellers: Under the Sea-Wind (1941), The Sea Around Us (1951), The Edge of the Sea (1955) and, most famously, Silent Spring (1962). Her slow process of gathering countless “kernels of fact,” as she put it, and transforming them through multiple revisions into literary prose sometimes caused her to “suffer tortures.” Carson’s able editors and equally skilled agent, Marie Rodell, learned to work well with her by sensitively pressing her about deadlines and providing perspective without limiting a project’s outcome.

From On a Farther Shore.

As a writer, Carson was most at home at the library, where she conducted meticulous research and corresponded with scientific experts and literary authors. Among the many portraits of influence Souder draws are ornithologist and underwater diver William Beebe, and two English authors: Richard Jefferies, whom Carson called her literary grandfather, and Henry Williamson, who was a generation younger than Jefferies. Carson, who went diving only once herself, explored the ocean aboard research and fishing vessels and, most intimately, from Atlantic island shores, especially those of Maine’s Southport Island. There, in 1952, she built a summer home and, as Souder gently relates, met the love of her life, neighbor Dorothy Freeman. With Freeman, she explored beauty—a liminal cave hung with “little elfin starfish,” a symphony by Gustav Mahler, a poem of T. S. Eliot’s. Such delving was vital to Carson’s gracefully embracing writing. Her thoughts went “down through the water,” she wrote, and through her research and imagination she discovered the lives of the creatures she was studying accurately and wholly—in the totality of their relationships. In her sea storytelling, time ranges from ephemeral to geological. Space reaches from abyss to stars and from southern marshland to Arctic tundra. Life is a continuum, forever changing and not changing—evolving, migrating, eddying in currents, eating and being eaten, with humans enmeshed within it all.

In 1958, Carson admitted to having “shut her mind” to the redirection of wartime technologies toward peacetime uses. She now opened it to courageously face the deeply troubling ways in which arrogant applications of science—part of the narrative of human control over Earth—were overwhelming the natural world she had believed was “forever beyond the tampering reach of man.” In a chapter titled “Earth on Fire,” Souder evokes the painfully disorienting “twin fears of the modern age”—radioactive bomb fallout and liberal pesticide use—and concludes with author E. B. White urging Carson to write about them. In the process of doing so, Carson explored ways to use science less crudely, corresponding about pesticide alternatives with experts including E. O. Wilson. Wilson recommended British ecologist Charles Elton’s new book The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants, an important influence on Carson’s work that Souder unfortunately neglects. Elton’s earlier work on food relationships had shaped American literary scientist Aldo Leopold’s ethical vision of “land health”—the capacity of the community of life for self-renewal—with which Carson was familiar. Elton’s later work, in turn influenced by Leopold, similarly encouraged Carson’s recognition of the vitality of biological variety to the health and wealth of ecological communities, an alternative to a chemical “rain of death,” in Elton’s words, as spraying with DDT and other pesticides was coming to be perceived.

Herring gulls can see phosphorescent dots on the sides of otherwise translucent big-eyed shrimp drifting below the surface of a nighttime sea, as Carson described in Under the Sea-Wind. In Silent Spring, with similarly sharp eyes, she made visible to an uninformed public the bodies of scientific evidence indicating that the hasty, widespread dissemination of radiation and pesticides was causing collateral damage to organisms that share, as Souder puts it, “a common biochemical evolutionary history”—in other words, all of us. Carson showed, now with volatile grace, how these poisons weave their ways through interconnected ecological food chains that include humans, threatening everyone’s health. The book’s reception was explosively polarized. It won awards and initiated the environmental movement, which led to legislation including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act. Strongly negative reactions came mostly from industry and government representatives with economic and political stakes in the matter—as Souder writes, “self-protective enclaves within what President Eisenhower had called the ‘military-industrial complex.’”

The scientific evidence in Silent Spring held up under intense scrutiny. Carson was right, Souder reminds us, and even some early, outspoken skeptics conceded that she was. It’s also worth remembering that Carson did not call for a complete end to chemical uses, as some detractors accused her of doing, but for use with precaution.

Another common criticism was one-sidedness. Recounting a point-counterpoint–style report aired on CBS in 1963, Souder shows how Carson could present her work as providing the missing piece on pesticide threats in a mosaic of opinions that otherwise overemphasized the chemicals’ safety and benefits for agriculture and disease control without accounting for costs such as evolving pest resistance and harms to health via biomagnification. Carson, who was suffering from the effects of radiation treatment for breast cancer, countered the arguments of government officials and industry spokespeople with calm and precision, winning the debate. Although many people admitted that she got the facts right, they nonetheless did not always embrace her overarching narrative. The battle her story ignited was not so much over the integrity of scientific knowledge as the worldviews that shaped responses to it.

Souder claims that environmentalism, with its core concern for health, need not have become a partisan issue, but that it did so because it began with Silent Spring and the fierce attacks it sparked. If this supposition is true, Sounder inspires the conclusion that it is because Carson’s outlook meant that health was a matter encompassing the totality of the world of life, thus requiring collective care, if not loving reverence, for Earth. This perspective threatened the predominant acceptance of violent control of nature as a means of speedily increasing economic wealth, and thus it evoked strong, if not always clearly reasoned, conflict. Carson was calling for a profound transformation of attitudes—one that would require not only fewer poisons but also a humbler worldview. “I truly believe,” she wrote, “that we in this generation must come to terms with nature, and I think we’re challenged as mankind has never been challenged before to prove our maturity and our mastery not of nature, but of ourselves.”

In the year between Silent Spring’s publication, now just over 50 years ago, and her death from cancer in 1964, Carson deepened her investigation into global climate change, a longtime interest of hers. A newly released report by the Conservation Foundation warned that heavy fossil fuel burning, which released the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide into Earth’s atmosphere, was likely to be accompanied by higher global temperatures, melting ice, rising sea levels and changes in distributions of marine species. We know now, based on strong scientific evidence, that these predictions and more are coming to pass. Like the still-rampant, careless dispersal of other pollutants, excessive greenhouse gas emissions by humans is a collective problem for Earth’s health today—which all the more urgently requires the daring exercise of just, collective care.

Julianne Lutz Warren teaches environmental studies at New York University; she received her Ph.D. in wildlife ecology and conservation biology from the University of Illinois–Urbana-Champaign. She is the author of Aldo Leopold’s Odyssey (Island Press, 2006) and the recipient of a 2013 NYU Martin Luther King, Jr. Faculty Award.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.