This Article From Issue

January-February 2002

Volume 90, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/2002.13.0

Devices & Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America. Andrea Tone. xviii + 366 pp. Hill and Wang (a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux), 2001. $30.

Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill. Lara V. Marks. xii + 372 pp. Yale University Press, 2001. $29.95.

Among the many scientific innovations that shaped 20th-century life, the development of oral contraceptives is notable for having brought "better living through chemistry" into intimate quarters. These two recent books offer reappraisals of the introduction of oral contraceptives into the older and often-controversial arena of birth control.

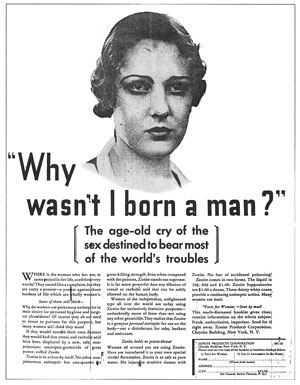

Andrea Tone's Devices & Desires explores the social history of contraception in the United States since the 1870s, paying close attention to the everyday production and consumption of birth control. The book features a remarkable cast of vendors and users of contraception, from the paralytic German émigré Julius Schmidt, who built a million-dollar condom empire from his knowledge of sausage casing, to Elizabeth Linden, a middle-class mother of three who celebrated the advent of the Pill in 1960. Tone's lively narrative presents a history marked by passion, conflict and often subterfuge, not only in the lives of individuals but in the marketplace. Established industries used the advent of government regulations to drive out smaller entrepreneurs, and advertisers played on fears of pregnancy to sell ineffective and even dangerous "feminine hygiene" products (such as the Lysol douche!).

From Devices and Desires.

Tone also discusses the role of legislation and litigation (from the Comstock Act in 1873 to the Dalkon Shield lawsuits a century later) in limiting contraceptive choice. Using evidence from credit reports to trial transcripts, she uncovers a vast record of both legal and illegal use of and commerce in contraceptives. Enforcement of the Comstock Act (which classified contraceptives as obscene) by Anthony Comstock's vice squad and the few postal inspectors on the lookout for obscene objects was remarkably minimal and had a strong class bias: The targets of suspicion were the "street and saloon" purveyors of illicit items, not established rubber and pharmaceutical houses. While Samuel Colgate was serving as president of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, his company was putting out promotional literature informing customers that Vaseline could be charged with salicylic acid to make a spermicide. Smaller entrepreneurs could rarely be so bold; they had to rely on creative relabeling of their wares to avoid being sanctioned.

The growing legitimacy of contraceptive devices in the early decades of the 20th century, Tone observes, owed much to the American experience of World War I. The U.S. military fought a losing battle against venereal disease with their abstinence programs and postcoital prevention kits. Despite the official disapproval of the military, American soldiers returning home brought with them a newfound appreciation for condoms. The federal government's growing commitment to public health overcame the Victorian ethos of self-control, and a 1918 court ruling allowed the sale of birth control "for the cure or prevention of disease."

The increasingly medical cast of birth control made female contraceptive devices more respectable. The 1930s saw the promotion of a prescription-only diaphragm—even though most women continued to obtain their information about birth control not from their doctors but through advertising (much of it misleading). Attempts at medical control of the dissemination of contraceptives thus predated the Pill.

Tone's account is richly textured, and she rightly points to the effect of the consumer movement on reception of the Pill over the course of the 1960s. The movement's impact on industry was also significant in response to problems arising from the Dalkon Shield, an intrauterine device that continued to be sold despite known health and failure risks. Eighteen deaths and 325,000 legal claims later, the promise of new or improved contraceptives has faded. The unresolved conflict between costly product liability and necessary consumer protection has led to a standstill in research and development.

Lara Marks's Sexual Chemistry lacks the human drama that makes Tone's book so engaging to read, but it does synthesize a great deal of historical information about the Pill's invention and use. Marks probes the multiple social and political contexts in which contraceptive science and medicine developed. For example, her attention to the global context for the Pill helps account for the growing American commitment to birth control during the Cold War: Controlling population growth was seen as a way to limit the appeal of communism to the "hungry masses" in the developing world. She recounts the usual story of collaboration between women patrons (Margaret Sanger, Katharine McCormick) and male scientists (Carl Djerassi, Gregory Pincus, Min Chueh Chang) in bringing the Pill into existence, but she includes as well the critical participation of government agencies, clinicians, technicians and even Mexican laborers. There are neither heroes nor villains in her telling, and she takes care to evaluate developments in terms of the medical practices and ethics of their era.

Marks does a good job of illuminating the unanticipated consequences of oral contraceptives for the progress of clinical testing and epidemiology. The contradictory and inconclusive studies on the relationship of the Pill to cancer, for example, spurred epidemiologists to combine enormous and heterogeneous data sets in order to ferret out patterns of disease causation. Less original are her chapters on the social reception of the Pill and the religious controversy it fueled. In the end, Marks's account shows that the path to the Pill was more circuitous and complicated than the conventional story indicates, but she fails to offer up a compelling new interpretation of the emergence and reception of oral contraception.

Taken together, these two books show how contraception became an aspect of modern health care, especially in the developed world. The business of birth control has become vastly more complex, involving regulatory agencies, research scientists and physicians, as well as companies and customers. What remains striking is how hesitant pharmaceutical industries were in the 1940s to pursue lucrative prescription contraceptives. Instead, it was feminist activists and patrons who prodded and paid for the development of oral contraceptives. Ironically, this did not prevent the Pill from being viewed by many women as an agent of coercion or control. Contraceptive innovations that have hit the market in recent years, including Norplant, Depo-Provera and the female condom, have failed to elicit the kind of sweeping consumer enthusiasm that greeted latex condoms and the Pill in decades past. In part, this may reflect a muted sexual sensibility in an age of AIDS—or perhaps it's just that reliable and safe contraception is now taken for granted.

But if the Pill no longer exists in the cultural imagination as an agent of sexual liberation, perhaps another prescription has taken its symbolic place: Viagra. If so, the medicalization of contraceptives may have been only the first stage of the medicalization of sexuality.—Angela N. H. Creager, History, Princeton University

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.