Collaboration: Ants, Art, and Science

By Rob Dunn

with Gabrielle Duggan and Adrian A. Smith

Artists and scientists can work well together when they share the same quarry.

with Gabrielle Duggan and Adrian A. Smith

Artists and scientists can work well together when they share the same quarry.

Last summer I spent a month with my family in the town of Delft, in the Netherlands. Delft was the home of Johannes Vermeer, famous for his paintings Girl with a Pearl Earring, The Milkmaid, and The Little Street. But Delft was also home to Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who discovered the existence of microscopic life and spent the rest of his life as its obsessive explorer.

Vermeer and Van Leeuwenhoek were both born in Delft in October 1632. They would have gone to the same market. That they knew each other, or at least had met, seems inevitable. The big question of whether the work of one man influenced the work of the other is the harder one to answer. The way this question is usually posed is to wonder whether Van Leeuwenhoek, with his single lens microscopes, influenced Vermeer’s use of the lens of a camera obscura to project images (and light) onto his canvas. But I wanted to know the opposite—how Vermeer and other artists might have influenced Van Leeuwenhoek.

When I was in Delft, the house in which my family and I stayed happened to be on a lot used by Vermeer’s aunt, Ariaentgen Claes van der Minne, to pen her animals. The lot was just behind the houses of Vermeer’s mother and sister. Vermeer’s aunt sold tripe. She had largely been forgotten by history until it was discovered that the alley beside her house on Vlamingstraat appears to be the same alley depicted by Vermeer in The Little Street. That we found ourselves sleeping in a house on the land where Vermeer’s aunt’s animals were fed, butchered, and buried was the kind of great fortune of which a biologist interested in art dreams. All the better that she sold tripe and I sometimes study the biology of intestines.

Olivia Sanchez Dunn

But it got better. When the house we were staying in was built, the land beneath it was partially excavated. The archaeologists took what they thought to be important and left everything else, in buckets. My son and I sat amid the contents of one such bucket, surrounded by the bones of pigs and cows, and also pieces of teacups and jugs (above).

I tell of the bucket and its contents because my moment among them led me toward a hypothesis about art, science, and Van Leeuwenhoek. Van Leeuwenhoek and the painters of Delft, as others have suggested, used similar technologies. At least some of the painters of Delft used lenses to project images (and to see them in new ways). Van Leeuwenhoek used lenses and light to see new, tiny worlds. The painters also used, of course, paintbrushes and ink to call attention to details the casual observer had missed. But they shared something else with the scientist: a common quarry.

Vermeer and several dozen other painters of Delft, including Carel Fabritius (who painted The Goldfinch), and Pieter de Hooch (who painted many famous scenes of houses as seen through doors), considered daily life. The painters depicted doors; Van Leeuwenhoek studied the dust on doors. They depicted food. He studied the life in foods. They painted cups. He looked at the life in cups. They implied the bones beneath bodies; he depicted the bones. The painters depicted men courting women; Van Leeuwenhoek drew sperm.

In short, both artists and scientists depicted the sort of bits and pieces of life I could see living in the grass or dead in the bucket. On the lawn, with the bones and vessels, I was sitting amid the quarry of the famous men of Delft, both the scientist (there really was just one) and the artists. It was this I found awesome, as we picked through the bucket. For a moment I too held parts of their quarry.

Maybe the discoveries of Van Leeuwenhoek and the paintings of Vermeer and others in Delft happened in the same time and place simply because of the particular culture and relative affluence of the moment. This would be unromantic, and yet it is possible. If there was an influence, though, I think it was not (as is often speculated) via a simple exchange, such as of Van Leeuwenhoek offering Vermeer a lens, but instead through the creation of a culture (and with it many influences and exchanges) in which art and science, at every intersection, had something to offer each other, something to offer in light of shared tools, shared physical acts (depicting or arranging a scene), and a shared quarry. These conditions, I hypothesize, make it easier for insights to flow from one field to another. It can happen, even, in the work of a single individual.

Leonardo da Vinci did some of his greatest work while dissecting bodies in the basement of the Santa Maria Nuova hospital. His dissections revealed new scientific insights (the discovery, for instance, of atherosclerosis), and yielded new art (the depiction of those tortuous arteries). In his moments beneath the hospital, the work of the artist and the work of the anatomist, the physical work, were indistinguishable. Both art and science required knives to see, metaphor to contextualize (the arteries were like rivers), and charcoal and brushes to depict.

Then there was Alexander Fleming, the microbiologist. Fleming discovered antibiotics. (It isn’t that simple, of course, but in art or science, is it ever?) He did so at a time in his life when he was also painting. He painted using bacteria of different colors and growth rates, which he inoculated strategically on Petri dishes so that at one moment in the growth of the bacteria, and one moment only, a picture would appear. This art required exactly the same physical skills as his work: the use of the loop to inoculate, the Petri plate, the bacteria themselves. It also involved the same attention to the unexpected, which was perhaps Fleming’s greatest skill. Fleming needed such attention to spot unusual bacteria that he might need for his art, but it was also what enabled him to spot a ring of dead bacteria surrounding a Penicillium fungus.

Artist Gabrielle Duggan and postdoctoral researcher Clint Penick endured tiring physical labor when digging to extract pieces of ant nest casts. Back in the laboratory of Adrian Smith, the pieces of ant nest cast were laid out and fastened together using flexible surgical tubing, a medium that Duggan also incorporated into her final artwork.

Raymond Goodman

If it is correct that art offers the most to science when both have common tools and common quarry (and often common physical actions), then art also provides a prescription for the sorts of modern contexts in which the two fields offer the most to each other, those in which artist and scientist might be mostly likely to thrive together. I think this is true, and along with my collaborators Gabrielle Duggan and Adrian Smith, I offer a recent project as a kind of case study of what is possible.

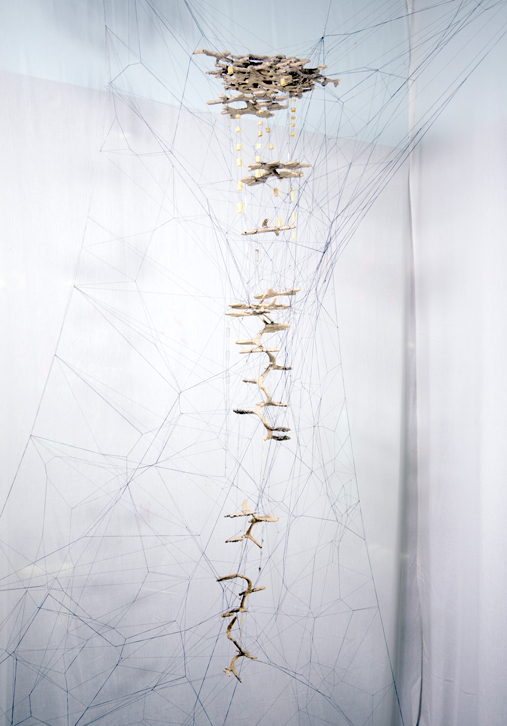

Gabrielle is an artist whose work often takes the form of temporary installations made of woven fiber structures. Tension anchors her installations as they span from floor to ceiling, suspending objects in the midst of intersecting lines. Adrian is a biologist who works on the behavioral biology of ants; he is head of the Evolutionary Biology and Behavior Research Lab at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and an assistant research professor at North Carolina State University. Adrian’s research often entails examining diverse ant societies, ranging in size from 10 to hundreds of thousands of individuals, and asking how these individuals cooperate to form a functional society—how the pieces make a whole.

I had brought Gabrielle together with Adrian and a group of other scientists focused on the places animals live, homes constructed of tunnels and chambers. At first, the connection was awkward. The language of art and that of science have diverged. There was in the first meeting a sense of dancing. Something raw and exciting was in play, but without rhythm or choreography.

The first good step forward came from Gabrielle. She noticed, in our very first meeting, something all of the scientists gathered had missed. We had pulled out, by way of explanation of our work, a series of drawings of the nest structures of rodents and then also photographs of casts of ant nests. It was the latter to which Gabrielle was drawn. For more than 50 years ant biologists have depicted this architecture by making casts of underground, excavated nests, casts rendered in metal, cement, or plaster. Casts of full-size nests range in vertical scale from inches, to human-sized, to too-big-to-get-out-of-the-ground-and-display. These casts are made by scientists in order to see what is invisible, to understand how ants build and carve, and to discover just what needs to be explained.

The act of being together in the same space, whether the field or the lab, carrying out similar physical tasks, made it easier to find a common language.

We were trying to think of new ways to compare the nest structures of a particular species with one another and with the nest structures of other species. We were talking about the structures using the language of architecture, as though the ant nests were apartments. Gabrielle noticed that if you travel down one of the tunnels of the ants, deep into the Earth, passing from one chamber to another, you often arrive at a dead end. You then have to come back up to the top of the nest to go down another tunnel. The tunnels, she said, if you spread them out, are more like subways than roads. This is true and biologically interesting; it presented us with new questions. Still though, the conversation, although fascinating, was clumsy, a slightly raw start, without a defined direction. Then Adrian invited Gabrielle to the field, to go see ants and to study their nests with him.

Adrian had begun to work with my postdoctoral researcher Clint Penick to make casts of ant nests, and he brought Gabrielle along to make a cast. They searched out an ant colony and began the process of pouring plaster into it, and then, piece by piece, digging the hardened plaster out. Working with Adrian in the field, Gabrielle felt as though she were in the early stages of doing art. She was finding the pieces she would work with. She was making and harvesting them. In “the field,” her work and Adrian’s work were not so different. Their tasks would also be similar when the cast of the nest came back to the museum. Adrian had originally intended to reassemble the cast as science; Gabrielle would, instead, assemble it as art.

For both Gabrielle and Adrian, the act of being together in the same space, whether the field or the lab, carrying out similar (or even shared) physical tasks, made it easier to find a common language with which to talk about their work; even when the specific terms used in ant biology and fine art are very different, those used for the physical work are less so.

The experience in the field with Adrian affected Gabrielle’s art directly: She used the material from the work—what she experienced but also the cast itself—to transform an ant nest cast into an art object. Gabrielle chose to arrange the cast as a fragmented deconstruction, not to be confused with an actual ant nest; its presentation emphasized its state as a referent, an image built of objects and yet referring to a process. To Gabrielle it was important to capture that the cast was not just a reflection of the original nest, but also a reflection of the nest and its colony in a particular ephemeral moment, in much the same way that a photograph might be. But could this process also really shape the science Adrian was doing, or was it “extra,” a way for Adrian to enrich his experience but without direct benefits for his ability to make discoveries?

In this case the experience in the field and lab with Gabrielle directly altered Adrian’s science. For Adrian, Gabrielle’s work reframed what casts of nest architecture are. By choosing to suspend the cast in fragmented bits, rather than displaying it in the form in which it came out of the ground and showing how the fragments connected, Gabrielle’s work emphasized the impermanence of the nest to which the piece referred. The hard plaster of the nest was permanent, but in the context of Gabrielle’s art it was making a statement about the ephemeral. To Adrian, seeing the cast this way reminded him of a reality often forgotten by ant biologists, that the cast is really a snapshot of a temporary condition of that colony, more a work in progress than a finished piece.

Raymond Goodman

To scientists, ant nest architecture is known to be fluid in some ways. Nests expand and deepen as a colony grows larger. But what if, by only admiring snapshots of these forms, we were missing even more fluidity in how ants construct and inhabit their nests? What if there were finer scale changes in architecture that were happening daily, and ant nest architecture is never actually completed? So Adrian started experimenting with the ants. A 24-hour time-lapse video from those experiments revealed the process of nest digging to be more than just excavation. While some ants moved soil and hollowed out more livable space, other ants constructed walls, refilling and refining the space that had already been excavated. Even in a short 24-hour period, nest architecture was observably fluid, constantly changing.

Gabrielle and Adrian’s collaboration evokes the history of art and science and some of the most powerful moments in both fields (Van Leeuwenhoek and Vermeer, Leonardo, Fleming), but it also offers something else, a way of imagining a series of collaborations between artists and scientists built not around insights or concepts, but instead around the common efforts required of both fields. I often host artists in my lab or facilitate connections between artists and scientists. The experience of Adrian and Gabrielle, along with my epiphany among the bones in Delft, made me think differently about how to make partnerships between artists and scientists most effective and about which such partnerships in the past had most influenced scientific discoveries. Here I mean the big past, but also my own specific past.

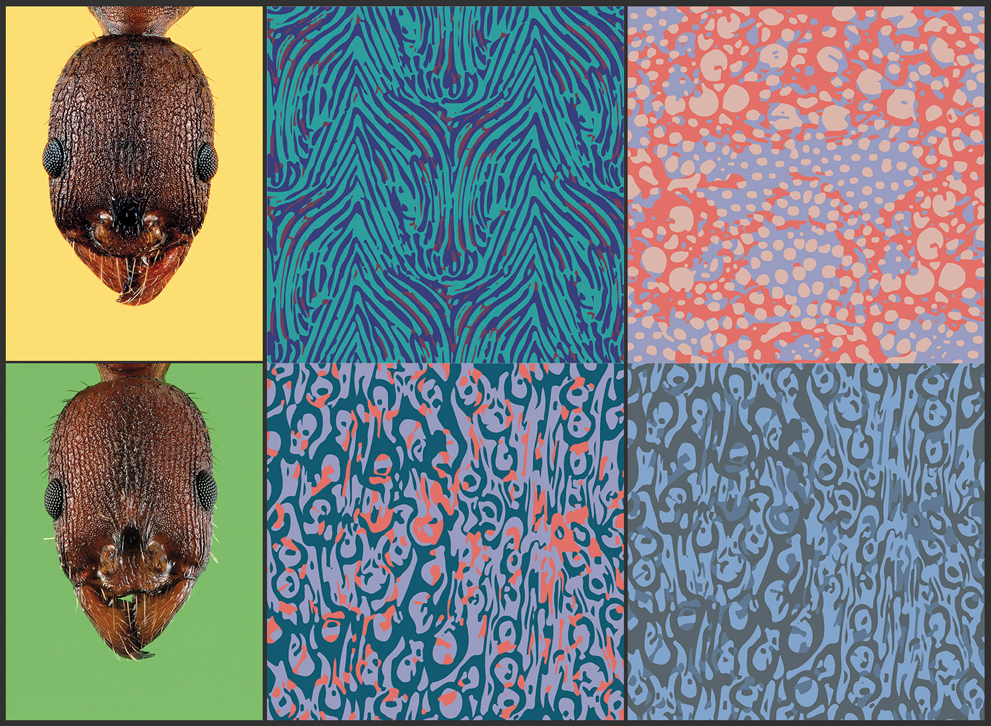

The year before, we had tried another collaboration with artists. That collaboration was focused, like the work on ant nests, on understanding a common quarry—in that case, the external skeletons of ants. Under a microscope, the skeletons of ants are often ridged and punctured. The structures of ants are wildly different, but these variances have gone largely unstudied by ant biologists. During an undergraduate class, the students and I, along with Clint and a group of postdocs, came up with the hypothesis that perhaps these bumps related to the ways ants defend against pathogens. Maybe bumpy exoskeletons favored beneficial bacteria that, in turn, helped to fight off microbes. The divots on the exoskeletons were habitats, or could be anyway.

Adrian Smith and Meredith West

This became an area of artistic and scientific exploration, as the first step was documentation of the patterns. I hired Meredith West, an artist who works with textiles, to work with Clint and Adrian to document the exoskeletons of the ants. Meredith would come to use tools similar to those they were using, but she introduced metaphors and language that were new to them (the concept of motifs, for instance). The result was a new approach to depicting the morphology of the ants, an approach more useful to science than what scientists had been using. In addition, the prints Meredith made were new to art. To Meredith, each of the prints has artistic meaning. To Adrian and Clint, each print shows the pattern of a particular ant’s head. These are patterns that evolved under natural selection for specific functions, patterns Meredith helped make easier to see and hence explain. The collaboration, grounded in common tools, common quarry, and unique metaphors, like that with Gabrielle, worked for both the artist and the scientists.

So far these examples are cases in which the shared quarry is something physical, such as the life in houses, arteries, the growth of bacteria, the nests of ants, or the skeletons of ants. But we also hope to extend just what the quarry can be. The common quarry can also, of course, be a concept, such as a theory about the way life evolves. A collaboration grounded in a common concept as quarry, rather than a common object, would be most exciting if the scientists were the ones to do the extra work of thinking about how they would display their understanding of the evolving, living world. We will host many more artists in our labs, while keeping in mind the benefits of shared tools, shared tasks, novel metaphors, and shared quarries.

This article is adapted from one that was published in the February 2018 issue of SciArt Magazine,www.sciartmagazine.com.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.