Climate-Disturbed Landscape

By Robert Chianese

Our disturbed Southern California environment may force us to acknowledge our changing relationship with nature.

Our disturbed Southern California environment may force us to acknowledge our changing relationship with nature.

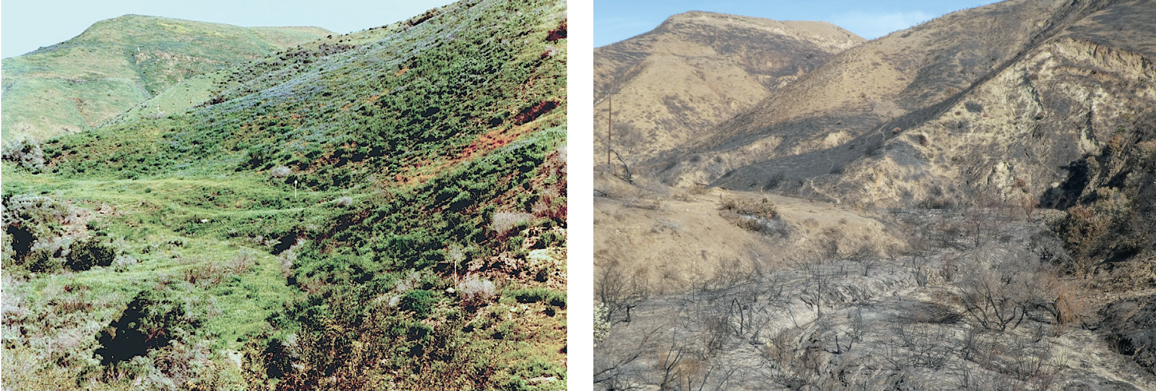

Nearly a year has passed since one of the biggest wildfires in California, the Thomas fire, consumed a quarter of a million acres in less than a month. Igniting northwest of Los Angeles in the foothills of Ventura and Santa Barbara counties, the fire destroyed 1140 square kilometers of homes, vegetation, and wildlife. After moderate rains in the spring, the coastal hills had some grassy cover, lupines pushed up through the sooty blight, and mustard sent out its yellow-tipped stalks. Tree tobacco flared its flowery tubes, and wild cucumber searched for remaining branches to climb. Charred lemonade berry trees sprouted shiny shoots at their base, and blue dicks (Dichelostemma capitatum), mariposa lilies, Indian paintbrush, evening nightshade, and even poppies bloomed again.

We seemed to be in a state of environmental grace—a respite from heat, wind, and the destructive downpours and mudslides that occurred weeks after the fires and were exacerbated by the torched ground cover, washing away houses and lives in nearby hilly Montecito. After conflagration, the greening enchanted us. It recalled for Southern Californians our tenacious coastal hillside “garden,” the grasses and chaparral that tint the hills green for part of the year, even though they have been diminished by droughts. Poet Andrew Marvell claimed that when we contemplate actual greenery, our minds invent even greener worlds:

Yet it creates, transcending these,

Far other worlds, and other seas;

Annihilating all that’s made

To a green thought in a green shade.

(“The Garden,” 1681)

The promise of renewal depends on soaking rains and steady aquifer-filling precipitation—not destructive “rain bombs,” the wet microbursts of intense wind and water. But as California Governor Jerry Brown has painfully suggested, drought, fire, hot winds, and mudslides may be our new normal. Unfortunately, we might have to be satisfied with a mentally made world of greenery, as climate warming across the globe continues, though fitfully, which will bring even more transformative effects to our environs.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens using modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2017) processed by the European Space Agency

Our burnt vegetation might come back only gradually, if at all. Plants that require fire to regenerate, such as soap plant and wild cucumber, begin to revegetate the hills only as long as the rains continue. Woodlands and forests, with their seeds destroyed by intense, hotter fires, will not regenerate easily and will become less diverse shrublands, says Kristen Shive, a forest ecology researcher at Save the Redwoods League. Hugh Safford, an ecologist at the University of California at Davis, predicts more ominously that western areas have burned too much and will not even produce shrubs, perhaps just invasive weeds.

Ongoing droughts in the western United States and the lingering effects of current (and likely future) fires produce a sense of dread and despair. In a previous column (May–June 2015), I explored how eco-art might help alleviate eco-anxiety. A new study by Helen Berry, professor of climate change and mental health at the University of Sydney, examines how ongoing alteration of our planet’s climate negatively affects our mental health, which is a neglected area of research. As we see the effects of climate change everywhere, we may not be able to turn to nature as a refuge, a source of health and mental renewal—and this loss presents a huge shift in long-standing values and an obvious source of despair. We may not be able to accept what we have wrought—or allow ourselves to see it. Connecting the dots between small individual acts and massive global effects is admittedly an intellectual stretch. Many people may remain in denial, but what about those who accept our complicity in heating the planet with our fossil-fuel burning?

We in the developed world may finally come to accept the economic and social damages from this persistent lack of rain and rise in atmospheric heat as the consequences of human greed, stubbornness, and folly. Nostalgic for greener times, we may find ourselves guilty of crimes against nature—a formulation often whispered in environmental writing but rarely stated openly, because such a judgment can evoke theology and a system of cosmic or terrestrial justice foreign to the objective frameworks of science. Yet, many scientists make ethical arguments against despoiling the planet and the disproportionate consequences for the affluent and for the poor.

Art may help us see our crimes against nature. Ventura artist Susan Petty has painted a famous Southern California land feature, known as South Mountain, completely denuded of vegetation—a radical outcome of extended drought and the way these hills looked after the fires of 2014.

Notably, the oil industry still works the very productive South Mountain, having pumped 158 million barrels from it since 1916, with 316 active wells today. The Thomas fire began in this region, connecting oil, fossil-fuel burning, climate change, and the drought-ramped fires. Petty gives us a straight-on view of the glaring Sun that cooks our petroleum emissions so we do not miss the ultimate source of our environmental threat, but she includes no hint of the oil production itself. Humans are absent from the scenery, and the painting by itself makes no argument about the sources of the altered land. Its argument requires no such elaboration and is starkly manifest to locals, who know the situation.

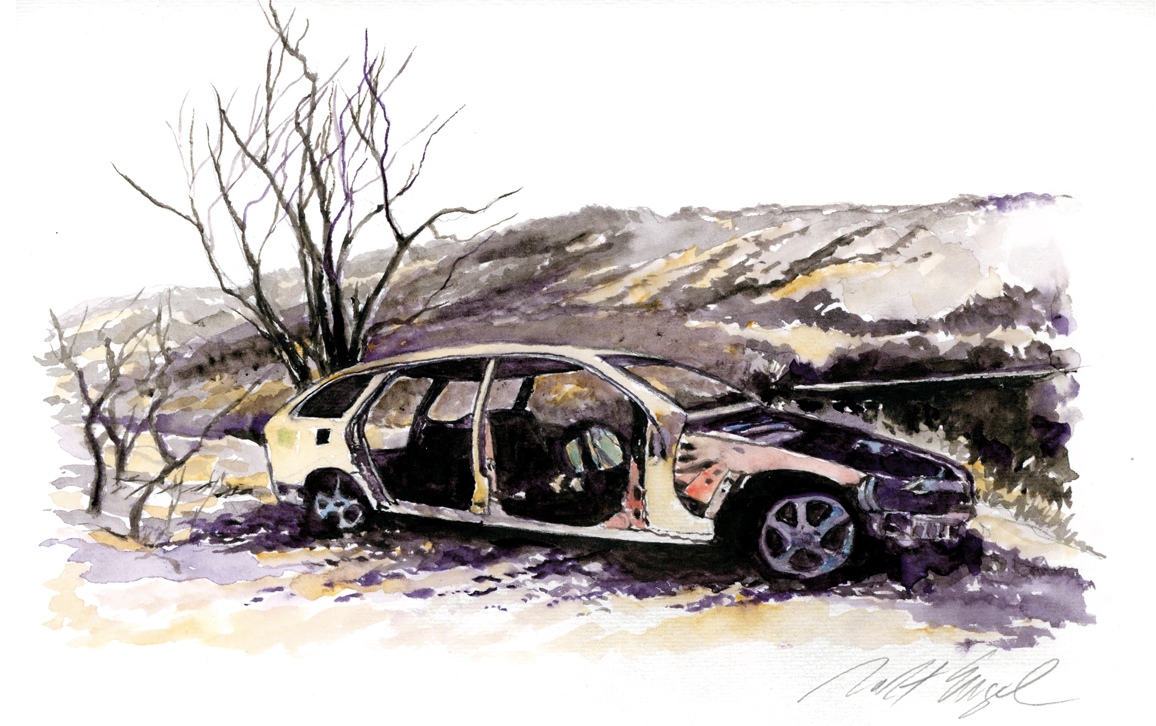

Robert Engel

In land with its vegetation dried, burnt, or consumed, we sense a new steepness and ruggedness as fire exposes outcrops, scarps, and ridges with more exaggerated dimensions in accented relief. Gullies, barrancas, and hillocks emerge. Remnants of homeless encampments also appear, set out with fire pits and glass bottle piles, and a few hulks of vehicles and discarded appliances turn up. This change reminds us that trees and brush soften the topography, gentling it, evening it out, and connecting peaks and valleys, crests and creases.

In another artwork, a stunning watercolor of a car’s charred remains, Ventura County artist Robert Engel revealed the connection between our car culture and the fire. The burned car looks on another oil pipeline in the background, a reminder of the sources of our disturbed and violent weather. The very ground seems oil-laced, almost shellacked, and may have ignited.

The scene is not too different from what’s happening in the real world. Homes have had to be rebuilt, and oil companies have had to verify the safety of thousands of wellheads and installations used in their operations. But the burn is front and center—for miles along the coast and the interior transverse ranges. What it reveals may be completely obvious, but not seen, so used to its presence we have become.

Aesthetic movements in the past have explicitly captured our damage to the land—mainly the Dust Bowl photographers and painters who recorded our active spoiling of the midwestern prairie in the 1930s. Alexandre Hogue’s Mother Nature Laid Bare (1938) foregrounds the plow as the ruinous culprit of desiccation, a metaphoric rapist, replete with abandoned farm, dead tree, and vulture in the background. The broken horse-drawn hand plow gives a clue to who is at fault here—a misapplied agricultural technique. Different methods of plowing finally preserved some soil from drought and wind, but Hogue’s painting suggests we have done more than misuse the Earth—we’ve killed it. And he prophetically hints at a grander destruction—the changing of the climate itself. This might be the origin of climate-change art, and its shocking message is difficult to avoid.

Most depicted landscapes scorched by fire omit the culprit—us. We are far removed from the scene in one sense, because our atmospheric pollution is essentially invisible and seemingly impersonal. But the massive Thomas fire revealed the human sources of this conflagration, because the burned hills and meadows exposed the extensive infrastructure of California’s oil and gas industry. Oil and gas are the raw materials of climate change, extracted from Southern California landscapes for more than 100 years. And we are the end users, supporters, and enablers of the oil and gas companies. Artists have yet to “see” this exposure as a fit subject for art—oil and gas wellheads, pumpers, valve stations, and miles and miles of pipe threading hills and jumping valleys now bared by fire. But photographs by me and others, along with some paintings, may help point the way.

In one photo, the edge of a burned barranca highlights a distant, high-pressure gas line slung over the chasm, with a burned truck hulk in the foreground. Use of natural gas may be cutting down on atmospheric carbon from coal burning, but here the fire exposes the actual path across the land that holds a high-pressure, 18-inch gas line in its shallow trench below—the delivery system of end-use atmospheric heating. This documentary photo thematically evokes both Hogue’s Mother Nature Laid Bare painting in foregrounding the immediate source of the ravaged landscape—trucks and autos—as well as marks the landscape with a semipermanent scar of our making. The dark synergies between the pipeline, truck, fuel, combustion, greenhouse gasses, drought, violent winds, and fire damage are much more explicit; the photo invites us to connect the various dots.

Even after the vegetation returns, with dead trees and patches of cooked soil in view, oil pipelines thread the hills as memento mori of our impacts. An unseen understructure of holes, metal and cement casings, and pipes rip through the ground. We have marked our landscapes with dire significance, still seen, even exaggerated, in spring’s fitful recovery, which is likely to prove short-lived. We are in the picture, the photo, or the painting no matter how we focus on the land itself. The specter or ghost in the garden is us—technically, our fossil-fuel infrastructures, marking the fiery circle of production, use, and all-too-obvious consequences. The drought, wind, and fires uncovered their ultimate origins.

Many expect the greening will not last this year, or next, or perhaps ever. We may have to get used to a desertlike transformation of our hills. How might we frame this, and what meaning can we impart to it?

The natural desert has a symbolic meaning in many cultures as a place of expulsion, a wasteland signaling religious punishment, social collapse, personal wandering, and potentially a stage for spiritual enlightenment. The imagery of nature in Western culture ranges from an Edenic paradise, a warring realm of anthropomorphic gods, a harsh unforgiving home for “unaccommodated man,” and a meaningless backdrop for the human drama, to a realm of physical processes, creatures, and principles worthy of intense study, a restorative romantic retreat from the hurly-burly of corrupt society, a resource for economic growth and development, a threatened realm we damaged and so must protect, and now the shared environment, locus of evolutionary, geologic, tectonic, and atmospheric processes that shape all life on the planet, including ours.

We have marked our landscapes with dire significance, still seen, even exaggerated, in spring's fitful recovery, which is likely to prove short-lived.

We commemorate purely natural disasters—such as volcanic eruptions and earthquakes, which can start massive fires and tsunamis—with plaques, monuments, and artworks. But events such as dam failures, river floods, tropical hurricanes, intense snowstorms, killer smogs, drenching microbursts, and contemporary droughts and wildfires remain mainly unheralded. We now recognize these exotic events as ultimately human-caused, but this understanding is slow in coming. This outcome is quite true of the Western states’ protracted drought and firestorms that have changed the face of the natural paradise, especially in California.

This change suggests the transformed landscape will itself become commemorative. A few rugged stumps might remain to mark a fire or flood, or a massive displaced rock may be left to memorialize some upheaval in the earth. But whole regions of transformed land, some actually becoming desertlike and unable to sustain previously native vegetation, will serve as their own dark or brown memorial. Looking at these scorched hills prompts contemplating the scale, intensity, and speed of the Thomas fire and others. They also call forth a friend’s loss and one’s lucky escape, so capricious the fires were in their leapfrogging of communities and individual streets. In other places, the fires wiped out whole suburban tracts but left the trees, provoking a wary regard for both the uncanny and miraculous.

Others might contemplate our folly in continuing to use fire-prone building materials and landscaping, overstretching water resources, and draining deep aquifers, while pushing to develop more housing and commercial properties with token concern for new water supplies. In our small city of Ventura, fire hydrants failed with the power outages, and many homes were saved only by roving Good Samaritans, as ours was, who used garden hoses at night to douse houses while their residents had to evacuate.

In the ever-expanding suburbanization of open space, beneficial controlled burns in the urban and wild interface become more dangerous. Biofuel builds and, of course, explodes. For many of us, the very blighted hillsides will speak condemnations of our follies as arrogant and self-deluded masters of the environment —sad, ineffective guardians, watchers, keepers, facing ourselves each day as we turn our heads to the hills or, more likely, away.

We may have to prepare ourselves for an uncomfortable realization—that we have turned the famous California paradise into a retributive desert. Even if we quickly curb our atmospheric pollution, climate change will likely continue for decades, if not centuries. What will future generations think of us?

Perhaps we can marshal technology to the rescue, replacing natural features with artificial ones. Our zoos, theme parks, and countless public and private gardens suggest how we might remake our hills if efforts at natural restoration fail. Artists might be drawn into the rebuilding of an artificial paradise. Such ersatz wild areas are shunned in Western culture as the profanation of the natural, but they have found some success. Singapore’s Supertree Grove, for example, replaces trees with bionic vertical gardens that conserve and recycle water, support vegetation, generate electricity, control airflow to nearby conservatories, and emulate principles of growth and design borrowed from nature and adapted to semiliving architecture.

Photographs courtesy of the author.

Art, technology, and biology reinforce one another in such artificial constructions. Virtual-reality replacements could crop up like fresh fields in the desiccated hills. Disney, after all, may have made the call for what society finds attractive about nature—a themed “land” of many biomes lumped together, where all the comforts and none of the buzzing afflictions of actual semiwild nature beset us. The future of climate change might involve a yearlong renewable pass to “Hillside Land” or, dare we say it, a virtual escapade into a Westworld simulation of California’s preconquest environment. This outcome would be a defeat for any restorationist’s vision of repair. We might even bioengineer life forms that can emulate the missing and suppressed hillside flora and fauna but do not need much water at all, with all of the attendant unanticipated side effects that might involve.

We would hope that efforts to curb fossil-fuel emissions, to use regenerative gardening to bring back and sequester carbon dioxide into the soil, and to develop new lifestyles and imaginative technologies for human society will go hand in hand with the obvious need for preservation and restoration of land and water already underway. But we can be sure that the future of climate change will shift more than temperatures and rainfall amounts. We can expect a firestorm of criticism from ordinary folks and environmentalists alike when faced with radical adaptations we may have to make to adjust and survive on a warming Earth.

New eco-art might expose our increasing damage to the land from which our eyes and consciousness still turn. It would revise the whole tradition of landscape art in the West, counter persistent depictions of nature’s glory, and become a more active witness of how we are degrading the planet. Such art would not only tie aesthetics closer to ecological science but also provide an expanded role for art as critical witness of the diminished natural world. This shift in landscape art might turn off nature lovers, but it could as well open them to seeing themselves inside the frame.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.