This Article From Issue

September-October 2005

Volume 93, Number 5

Page 467

DOI: 10.1511/2005.55.467

Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo and the Making of the Animal Kingdom. Sean B. Carroll. xiv + 350 pp. W. W. Norton, 2005. $25.95.

All plants and animals, including humans, are essentially societies of cells that vary in configuration and complexity. As Darwin's theory made clear, these multitudinous forms developed as a result of small changes in offspring and natural selection of those that were better adapted to their environment. Such variation is brought about by alterations in genes that control how cells in the developing embryo behave. Thus one cannot understand evolution without understanding its fundamental relation to development of the embryo. Yet "evo devo," as evolutionary developmental biology is affectionately called, is a relatively new and growing field.

Sean B. Carroll, as a leading expert both in how animals develop and in how they have evolved, is ideally placed to explain evo devo. His new book on the subject, Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo and the Making of the Animal Kingdom (the title borrows a phrase from Darwin's On the Origin of Species), was written, he says, with several types of readers in mind—anyone interested in natural history, those in the physical sciences who are interested in the origins of complexity, students and educators (of course), and anyone who has wondered "Where did I come from?" Carroll has brilliantly achieved what he set out to do.

One of the most striking discoveries of the last half-century has been that, despite the fact that animals differ greatly in appearance, common principles control their development from a single fertilized egg. They even have in common many master genes—genes that control many aspects of development. One can almost imagine Drosophila fruit flies saying to one another that they are amazed at how similar humans are to them. Indeed, many of the genes that have been identified as controllers of vertebrate development were originally discovered in these flies.

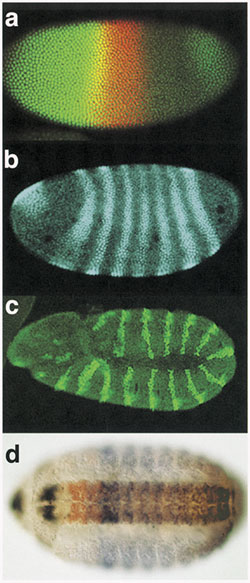

It's a key point that when and where genes are expressed determines how animals develop. The control regions of the genes (switches that change an existing pattern of gene activity into a new pattern of gene activity) are crucial, as Carroll makes clear, and one gene can have many control regions. (For example, in the fruit fly, there is a group of genes—known as the pair-rule genes—that express proteins in seven stripes along the body axis of the embryo [see illustration on next page]; each of these genes has seven discrete control regions, and each region specifies one stripe.) It is thus unsurprising that 95 percent of the genes that code for proteins are similar in humans and mice. Evolution of control regions has made us human—and different from our primate ancestors.

From Endless Forms Most Beautiful.

Carroll explains the basic tool kit for development that all animals share, placing particular emphasis on Drosophila. He introduces both Hox genes, which are considered master genes, and widely used intercellular signaling molecules such as the proteins specified by hedgehog genes. It is striking how few signaling molecules animals use in development. This is because the same molecules can be employed again and again, as cells will respond differently according to their genetic constitution and developmental history.

Carroll doesn't give much attention to the fact that a cell has a positional identity (based on the position it occupied on the axis of the body of the early embryo) or to how that positional identity is acquired. Nor does he delve into how a cell senses its position and figures out how to act according to its genetic constitution and developmental history, thereby differentiating to give any imaginable pattern. Consider that a change in a single Hox master gene can convert the antenna of the fly into a leg. There is evidence that cells in the leg and those in the antenna have the same positional identity. It is somewhat embarrassing that we still do not know how the change in that particular Hox gene controls the response of all those unknown downstream genes to make a leg rather than an antenna. And this downstream target problem is present for all Hox genes.

Carroll emphasizes that individual animals are made up of similar parts, such as vertebrae, bones in fingers and spots on butterfly wings, and that modular construction played an important role in evolution. He is a supporter of Williston's law, which states that "in evolution . . . the parts in an organism tend toward reduction in number, with the fewer parts greatly specialized in function." I must confess to finding the idea of modules not that easy to appreciate. Is, for example, the leg/antenna basic structure a module?

The earliest complex animals, fossils of which were found in the Burgess Shale, appear to have arisen about 500 million years ago, over a period of some 15 million years. Evidence from evo devo shows that all the genes for building those complex animals existed long before that morphological explosion. The dominance of arthropods at the time of the explosion may have been due both to Williston's law and to the power of Hox genes to specify differences between the body segments that formed different appendages at specific positions along the body. But how, asks Carroll, did the number of distinct appendage types increase? His answer is that the relative shifting of Hox genes could have provided the mechanism. That still leaves a big problem—how did arthropod appendages such as limbs and wings evolve? An answer lies, he says, in the origin and modification of the ancestral biramous (forked) limb. But even if the origin of the limb can be explained, wings are even more difficult. One answer is that they evolved from the gills on the limbs of aquatic ancestors.

But this conclusion raises a key, and much neglected, problem that even Carroll does not properly explore. If evolution proceeds in small steps, what were the intermediate stages in the evolution of wings from gills, and what was the selective advantage of each of those forms? How could the intermediate structures have been an advantage before the animal could fly? One possibility is that they played a role in thermoregulation, but there is no good evidence for that hypothesis. This is a general problem in evo devo, and Darwin fully understood the difficulties it poses.

A related problem is how to explain the evolution of the autopod—the digits—from fins. One possibility is that the autopod is merely a distal extension of the mechanism that gives rise to more proximal elements, such as the humerus, radius and ulna. A much more difficult problem is raised in the evolution of development itself. Gastrulation (during which an embryo forms its innermost, middle and outer layers) occurs in the early development of all animals and has evolved in a variety of ways related to later development; it is at present not possible to account for the intermediate forms or their advantage to the animal. Although evolution, as François Jacob pointed out, tinkers with what is there, rather than inventing something new, these problems remain unsolved.

A nice example of what could be considered clever tinkering is butterfly spots. Each spot appears to evolve its shape, color and size independently of other elements. Evolution has tinkered not only with the qualities of each spot, but with the making of the spot itself. Carroll's group discovered that at the center of each spot, the gene Distal-less (a key gene controlling the distal development of appendages such as insect limbs) is expressed and initiates spot development.

Even the evolution of humans can be thought of as tinkering with the genes of our primate ancestors. But this view is totally unacceptable to religious creationists. Carroll criticizes their views and emphasizes how important it is for evo devo to be taught in schools.

Evo devo is fundamental to understanding the biological world we live in, including ourselves. This is a beautiful and very important book.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.