This Article From Issue

November-December 2011

Volume 99, Number 6

Page 503

DOI: 10.1511/2011.93.503

POX: An American History. Michael Willrich. x + 422 pp. The Penguin Press, 2011. $27.95.

Historian John Duffy has noted that, in the late 19th century, “The diseases which were most effective in precipitating social change were those with the greatest shock value.” And throughout human history, few diseases have shocked communities so greatly as smallpox. In Pox: An American History, Michael Willrich describes a five-year wave of smallpox epidemics that swept the United States starting in 1898. “The history of these American epidemics,” he notes, “is, inescapably, a history of violence, social conflict, and political contention.” And as he shows in this engrossing book, the epidemics did precipitate social change: Smallpox became a key battleground in the struggle for individual rights in the Progressive Era.

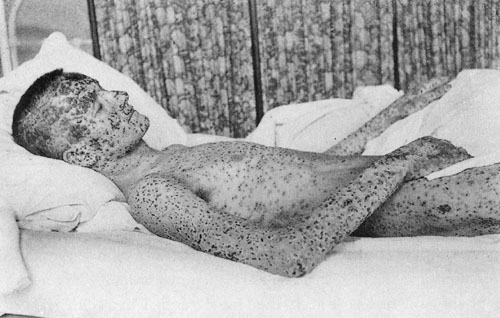

From Pox .

Smallpox wasn’t the most dreaded disease of the Victorian era—cholera and yellow fever generally took pride of place. But variola had some unique characteristics: An effective, but imperfect, vaccine for it existed; and a new, less deadly strain of smallpox had recently emerged, cutting the fatality rate from 25 percent to 1 percent. In addition, vaccination for smallpox was risky—it could cause pain, sickness and even death. Those facts led many to question the extreme tactics often employed to counter the disease.

Those extreme tactics, which were used by both civilian and military medical teams, are vividly portrayed in the book. Here’s Willrich’s description of steps taken during a New York outbreak in 1901:

They followed the same method on each block. With policemen stationed on the roofs, at the front doors, and in the backyards, doctors and police entered the tenements and rapped on doors, rousing men, women, and children. Frightened and furious, the residents moved into the lighted areas, where doctors inspected their faces for pocks and their arms for the mark of vaccination. . . . Everyone lacking a good mark had to submit to vaccination.

Willrich tells of one North Carolina official who opined that the best cure for lingering doubts about vaccination was “a good first-class case of small-pox.” He also notes that health officials across the country called smallpox “the fool-killer.” The emergence of smallpox in a community “killed fools” in more ways than one: It encouraged the unvaccinated to get vaccinated, and it preferentially infected those who chose not to.

But Willrich is clearly most passionate about the legal history. He devotes most of a chapter to the fascinating story of Jacobson v. Massachusetts, a case that he says became the epidemic’s “most important legacy.” Henning Jacobson was a Swedish-born Lutheran minister in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who refused to comply with the town’s mandatory vaccination order during a moderate epidemic. Found guilty of “the crime of refusing vaccination,” rather than pay the $5 fine levied against those who did not submit, Jacobson appealed his conviction, first to Middlesex County Superior Court, then to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and finally to the U.S. Supreme Court, claiming that the compulsory vaccination law “violated . . . the ‘spirit of the Constitution.’” Jacobson maintained that he had experienced “great and extreme suffering” when he had been vaccinated as a child in Sweden, and that one of his children had also experienced adverse effects when vaccinated, so he was convinced that some hereditary condition made smallpox vaccine hazardous for his family. His attorney argued that because the law made an exception for children, but not adults, with special health conditions, the law violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause.

The court’s 7–2 decision in favor of Massachusetts’s compulsory vaccination law became, and remains, a hallmark of progressive jurisprudence. Justice John Marshall Harlan stated in his opinion that

Society based on the rule that each one is a law unto himself would soon be confronted with disorder and anarchy. Real liberty for all could not exist under the operation of a principle which recognizes the right of each individual to use his own, whether in respect of his person or his property, regardless of the injury that may be done to others.

The decision did, however, put some limitations on police power, and Harlan stated in his opinion that the statute was not applicable to an adult for whom vaccination would be cruel and inhuman because of some particular condition of his or her health. (He did not believe, though, that Jacobson should be exempted.)

The Jacobson case occurred at a tumultuous time for the country and was central to the transformation of the relationship between the individual and the state that took place during the Progressive Era. Willrich makes it clear that antivaccinationism at the turn of the century was not just an antiscience Luddite movement, but also an expression of tensions over increasing governmental activism. As scientific medicine made vaccination safe and effective, and government began to compel its adoption, a serious movement rose to challenge what was, at the time, a change in the nature of the relationship between the individual and the state.

The question of what the limits of state intervention should be is overbroad, for the answer varies depending on the intervention and can change over time as circumstances change. In this regard, the law, and society more generally, must evolve in response to scientific progress. Questions about individual inviolability do not arise unless there is a necessity to act (the threat of disease) and effective action that can be taken (vaccination).

Given the risks and benefits of both action and inaction, the issue is, What role should the state play in regulating individual and group choices? There is no place for absolute constraints, although in practice some constraints are universally objectionable (those prohibited by the First Amendment, for example). But when a minor intrusion would yield a major benefit, and we believe ourselves constrained—whether from philosophy, religion, or law—from acting, perhaps we should acknowledge the fallibility of our abstract ethical reasoning, and do the thing that saves lives.

Through the prism of one disease and our efforts as a society to control it, Willrich gives us a microcosm of American political thinking in the decade spanning the turn of the century. The questions asked then are not unlike those we confront today—none more so than, What should be the limits of state power in regard to human health?

Ryan Seals is a graduate student in the Department of Epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.