This Article From Issue

November-December 2012

Volume 100, Number 6

Page 514

DOI: 10.1511/2012.99.514

NETWORKED: The New Social Operating System. Lee Rainie and Barry Wellman. xiv + 358 pp. The MIT Press. $29.95.

Lee Rainie and Barry Wellman have written an excellent new book on the effect of the ubiquitous Internet on society, using information on the latest Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project. In Networked: The New Social Operating System, the authors describe a “triple revolution” brought on by ICTs (information and communication technologies) and comprising social networking, the Internet and mobile information technology.

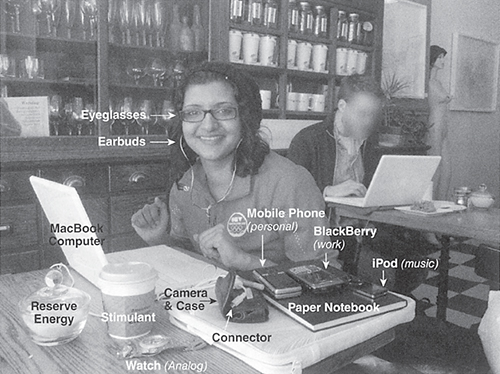

From Networked.

The technologies of the triple revolution, the authors write, allow us to connect with a larger, more diverse network, including close and distant friends and acquaintances. They make it possible to gather new and useful information in quantities and at speeds heretofore not experienced by humans. And they let people connect with others while on the go, meaning we are accessible in a way that only emergency personnel doing shift work used to be. The result of these frequently discussed changes, according to Rainie and Wellman, is a new framework—or “social operating system,” as they put it—which they call “networked individualism.” The new system has four central traits:

The social network operating system is personal— the individual is at the autonomous center just as she is reaching out from her computer; multiuser— people are interacting with numerous diverse others; multitasking— people are doing several things; and multithreaded— they are doing them more or less simultaneously.

This system, they write, is encouraging the formation of new kinds of community that serve people well.

The conclusions the authors draw run counter to the pessimistic ruminations of much of the older intellectual world, who see people drawing apart from one another while glued to their computers and mobile phones. In contrast, Networked is dedicated to the proposition that the new social operating system empowers individuals by allowing them to reach out to close and distant friends, even strangers, in a way that small-group–oriented communities never allowed. The statistics quoted here are as multitudinous as those detailed in Robert Putnam’s book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (2000) — but they tell a very different story. Rainie and Wellman discuss a survey suggesting that among heavy Internet users, there was an increase of more than one third between 2002 and 2007 in the number of friends seen in person weekly. They speak of the tremendous advantage of keeping in touch with weak ties (or consequential strangers, as Melinda Blau and Karen Fingerman have called them), who may be helpful when one is going through a difficult transition like unemployment or illness. The examples they cite make clear how having a chronic or acute illness is a much less lonely ordeal than it once was, thanks to the opportunities most people now have to compare notes and share information. The Internet, according to this book, allows us to keep up a much larger personal network on an intermittent basis (as on Facebook) without expending inordinate time or money on the endeavor. Over and over, the authors tell us they have evidence that technology is making us more connected that ever, noting, “People are not hooked on gadgets—they are hooked on each other.”

Other benefits the authors describe include less-hierarchical relationships at work and an intertwining of home and workplace not seen since farmers worked in fields adjacent to their homes. Voluntary and religious organizations have given way to more “ad hoc, open, and informal networks of civil involvement and religious practice”; blogs and YouTube channels allow people to engage in creative expression and find communities of people who share their interests.

Rainie and Wellman admit that the revolution caused by the Internet and its progeny, the smart phone, is a complex one:

Some of the changes created by networked individualism are beneficial to people and make society better while others are challenging to personal fulfillment and make society harsher. Some of the changes just make it different in neither a positive nor a negative way.

For better or worse, we’re now in a committed relationship with the Internet, and if we’re open to learning how to use it, we can make it work to our great advantage. But it requires much extra effort and time to decide what information and connections to pursue, because so much more is available for our perusal. Stories of college students’ planning of parties using communication tools from texting to Facebook are included to acquaint the older generation with the amazing social habits of the younger one.

Rainie and Wellman make compelling points about the advantages of the revolution they describe. But I wish they had addressed in greater detail some of the concerns I and others feel about our new networked life, as Sherry Turkle did in her 2011 book Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other (which I reviewed for an earlier issue of American Scientist) . What everyday comforts might we have lost because of this incredible revolution? It often seems that people’s passions and interests are so diverse that conversation about a common topic is a little harder to come by. Who reads the same books, newspapers or magazines now? Who even reads when communication needs to be kept up so frequently, and there are so many fascinating videos out there? Come to that, who watches the same movies or TV shows when diverse choices cater to so many particular tastes? What is the likelihood of receiving even a 50 percent rate of RSVPs to a gathering two weeks away when everyone is keeping their options open? (They don’t think of themselves as cruising for a better deal but don’t want to be expected to commit so far in advance.) How often can you invite people to dinner and expect that they might all be able to eat the food of the host’s choosing? The gist of this revolution is that everyone’s identity is formed more on the basis of having things their own way and not having to compromise for the convenience of others. Identity always had to do partly with matters of taste, but people had a certain satisfaction in being flexible, which offered a gracious civility that led to greater connectedness. But now it would seem that compromise is associated with not knowing who you really are.

Networked does a great service in reassuring us that people are still vitally interested in connection and can use their gadgets to good avail. But at the end of the book, I wasn’t quite convinced that all is well. That checking e-mail can be addictive has become a truism. And the danger of those gadgets seems to me to be that even when we’re connecting with others face to face, a small part of our brain is preoccupied with whether a truly exciting e-mail or text is about to arrive. In other words, have we all gotten so busy waiting for the next great thing that the joy of being with those we love has become permanently compromised?

Jacqueline Olds is associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. She teaches child and adult psychiatry at the McLean and Massachusetts General Hospitals and maintains a private psychiatry practice in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She is the author, with her husband Richard S. Schwartz, of The Lonely American: Drifting Apart in the Twenty-first Century (Beacon Press, 2009) and Marriage in Motion: The Natural Ebb and Flow of Lasting Relationships (Perseus Publishing Group, 2000), and, with Schwartz and Harriet Webster, of Overcoming Loneliness in Everyday Life (Carol Publishing Group, 1996).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.