Science and Suffrage

By Patricia Fara

During the First World War, rich connections between science and suffrage arose as women played crucial roles in STEM fields.

During the First World War, rich connections between science and suffrage arose as women played crucial roles in STEM fields.

The prominent role of women in the workforce during the Second World War is widely known and celebrated. Less commonly understood are the crucial contributions made by women who stepped into positions traditionally held by men—including scientific and engineering roles—during the First World War. Perhaps even less familiar is the relationship between these contributions and the passage of women’s suffrage laws soon after the war’s end. Women in the United States, for example, attained suffrage in 1920. British women gained the vote, with some restrictions, in 1918. (The Representation of the People Act 1918 granted voting rights to all men, as well as to women over 30 who met minimum property requirements. Suffrage was extended to all British women over 21 in 1928.) In A Lab of One’s Own: Science and Suffrage in the First World War, historian Patricia Fara explores the connections between science and suffrage in the United Kingdom during the early 20th century and tells the stories of women who worked in fields as diverse as geology and medical research during the war. The centennial of Armistice Day, on November 11, offers an opportunity to reflect on the First World War and the countless changes it wrought—militarily, politically, socially, and scientifically.

From A Lab of One's Own. Courtesy of Oxford University Press.

Caroline Haslett was just one among many thousands of young women whose lives were transformed by the First World War. Through their struggles, setbacks, and successes, they collectively influenced future generations. Her experiences illustrate how the war permanently altered scientific, medical, and technological prospects for women. A suffragette with a weak school record, she became an eminent international consultant on the domestic uses of electricity, educational reform, and industrial careers for women. She used her influence to alter the scientific careers of countless schoolgirls all over the world.

Haslett was judged a lost cause by her teachers because she never could learn how to sew a buttonhole. As a teenager, she left her Sussex village for London and—to the alarm of her strict Protestant parents—joined Emmeline Pankhurst’s suffragettes. When the War started, she was working as a clerk in a boiler factory, but during the next four years she was repeatedly promoted to replace men who had left to fight. By 1918, she was running the London office, visiting customers such as the War Office to discuss contracts, and astonishing staid civil servants with her expertise in a man’s domain. After being trained as an engineer by her enlightened employers, in 1919—still in her early twenties—Haslett began managing the newly founded Women’s Engineering Society. She was determined to consolidate and expand still further the opportunities for women that had recently opened up. Electric technology—dishwashers, vacuum cleaners, washing machines—would, she believed, free women of drudgery, liberating them to lead a higher form of life. She envisaged “a new world of mechanics, of the application of scientific methods to daily tasks . . . a great opportunity for women to free themselves from the shackles of the past and to enter into a new heritage made possible by the gifts of nature which Science has opened up to us.”

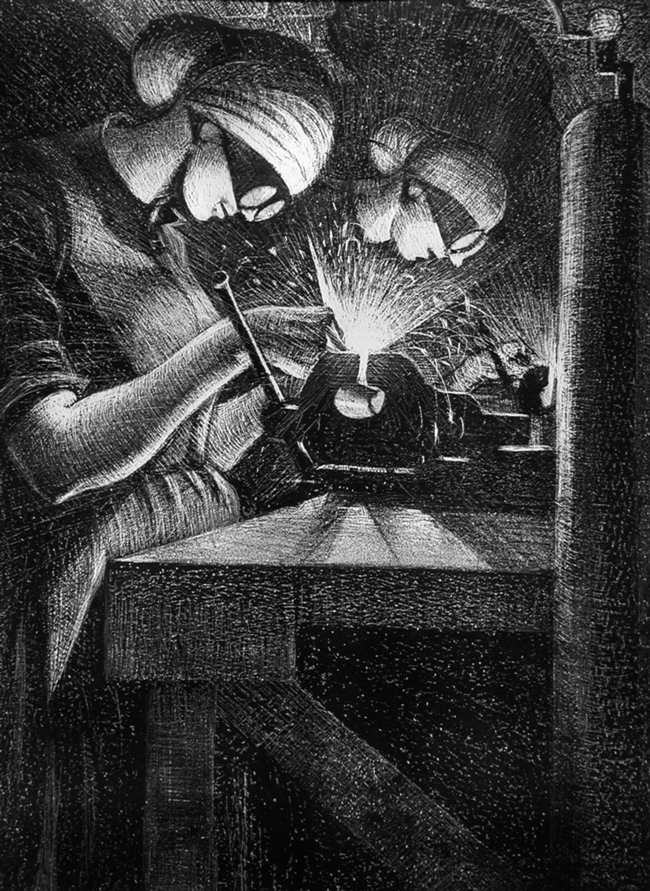

Christopher Nevinson, The Acetylene Welder, 1917, lithograph. From A Lab of One’s Own. Courtesy of Oxford University Press.

At the end of the war, 3 million women were working in industry. Like Haslett, some of them had the advantages of good grammar and the right sort of accent, but many were relatively uneducated—domestic servants, barmaids, and shop assistants who had seized the opportunity to escape from their menial occupations. Critics savagely denounced them either for abandoning their natural sex to behave like men, or for being spendthrift prostitutes. Overcoming the nation’s reservations, these hard-working wage earners proved their capabilities. By 1917, even Herbert Asquith, long a fierce opponent of female suffrage, had been converted. “How could we have carried on the War without them?” he asked; “Short of actually bearing arms in the field, there is hardly a service . . . in which women have not been at least as active and as efficient as men.”

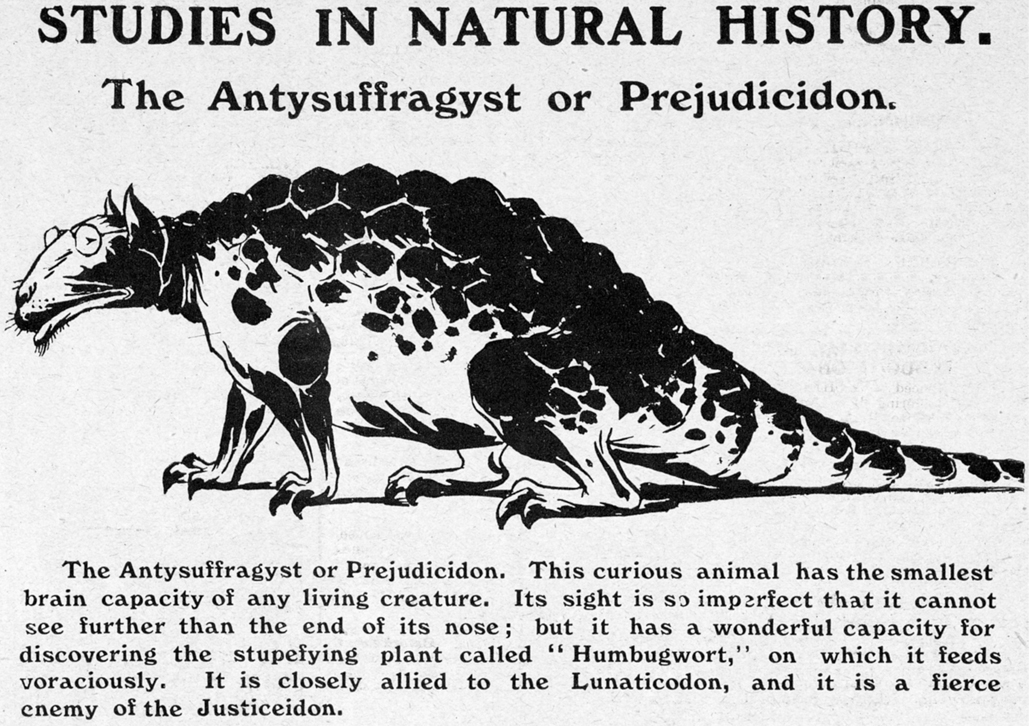

“The Antysuffragyst,” The Vote, September 26, 1913. From A Lab of One's Own. Courtesy of Oxford University Press.

Would women [in Great Britain] have won the vote in 1918 without these dedicated wartime workers? Why was the vote given to impoverished men but not to affluent young women? Did the militancy of the suffragettes harm or hinder their cause? Those remain some of the unanswerable what-if questions of history. What does seem clear is that public opinion was nudged toward approving female suffrage in recognition of women’s wartime contributions. In 1917, the Prime Minister David Lloyd George told Parliament, “I myself, as I believe many others, no longer regard the woman suffrage question from the standpoint we occupied before the war. . . . The Women’s Cause in England now presents an unanswerable case.” Addressing a less select audience, the Daily Mail delivered the same message: “The old argument against giving women the franchise was that they were useless in war. But we have found out that we could not carry on the war without them.”

From A Lab of One’s Own, by Patricia Fara. Copyright © 2018 by Patricia Fara and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.