This Article From Issue

January-February 2020

Volume 108, Number 1

Page 12

In this roundup, managing editor Stacey Lutkoski summarizes notable recent developments in scientific research, selected from reports compiled in the free electronic newsletter Sigma Xi SmartBrief.

Bison Create Their Own Spring

Creative Commons

Bison cause grasslands to maintain spring-like conditions longer, according to a study conducted at Yellowstone National Park. Biologist Chris Geremia and his colleagues found that animals that graze in large herds, such as bison and wildebeests, act as “ecosystem engineers,” creating and perpetuating springtime conditions. The animal herds increase plant productivity by eating young sprouts, and their feces and urine fertilize grasslands to stimulate new growth. The researchers compared vegetation growth in large bison enclosures over a five-year period and found that more intense grazing caused the grasslands to green up earlier, more intensely, and for a longer duration. This study complicates the green wave hypothesis that grazing animals move to higher elevations to follow the onset of warm weather. The bison continued to graze on new growth without moving elsewhere when springlike conditions had left fields of the same elevation.

Geremia, C., et al. Migrating bison engineer the green wave. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913783116 (November 21).

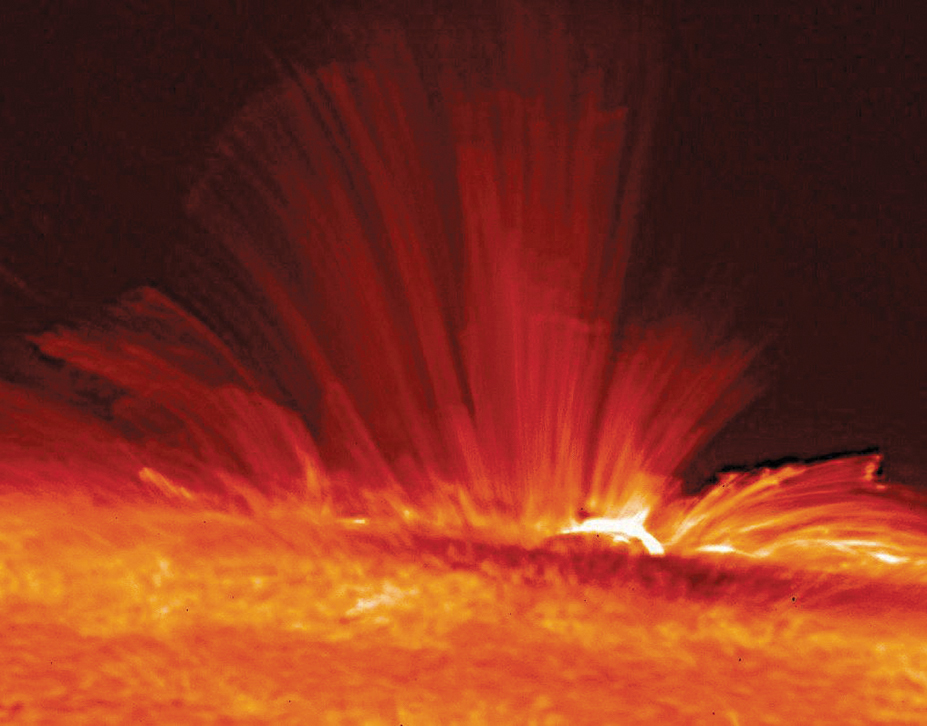

Solving a Solar Mystery

Images from the Big Bear Solar Observatory are helping scientists understand why the Sun’s atmosphere, or corona, is so much hotter than its surface. The corona is the halo around the Sun that is visible during solar eclipses. This halo is apparently heated by jets of plasma called spicules that shoot out from the Sun, and the images are clarifying how these spicules are created. The Sun’s surface is covered in a magnetic network of positive and negative polarities. The observatory captured images of opposite polarities colliding, causing a magnetic flux that ejected superheated spicules into the corona. The international collaboration of scientists who studied the images published their findings within days of NASA’s first release of data from the Parker Solar Probe. (For an interview with the probe’s namesake astrophysicist, Gene Parker, see “Parker, Meet Parker,” November–December 2018.) Researchers are combing through that trove of information now, and we will likely learn much more about the Sun’s workings soon.

Hinode, JAXA/NASA

Samanta, T., et al. Generation of solar spicules and subsequent atmospheric heating. Science 366:890–894 (November 15).

Vulnerability to Rising Seas

A new study triples previous estimates of the number of people likely to be displaced by sea-level rise and coastal flooding. Most previous estimates were based on data from NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, but that research effort’s spaceborne technology has a tendency to overestimate elevations by as much as two meters. Researchers at the nonprofit Climate Central used a new digital elevation model called CoastalDEM, which is designed to eliminate some of that bias. The resulting analysis indicates that, assuming a low level of carbon emissions over the next 80 years, 190 million people currently live in areas that will be underwater by the end of the century. If carbon emissions are high, that number grows to 630 million people. In either scenario, more than 70 percent of the people currently living on at-risk land are in just eight countries, all of which are in Asia: China, Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Japan.

Kulp, S. A. and B. H. Strauss. New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding. Nature Communications doi: 10.1038/s41467-019 -12808-z (October 29).

Hiccups Help Wire Baby Brains

Every movement newborn babies make helps them to learn, even when that movement comes from an involuntary respiratory function such as hiccups. A team of neuroscientists at University College London analyzed the brain activity in 13 infants while they had the hiccups and found that the movements of their diaphragms evoked significant activity in their brains’ cortexes: two large brainwaves, followed by a third. The researchers theorize that the babies’ brains are learning how to control respiratory muscles so that the babies can later move their diaphragms voluntarily—to take a deep breath, for instance. The third brainwave was similar to those evoked by noise, suggesting that the babies are learning to connect the sound of a hiccup with the sensation of hiccuping—a key development in multisensory processing.

Whitehead, K., L. Jones, M. P. Laudiano-Dray, J. Meek, and L. Fabrizi. Event-related potentials following contraction of respiratory muscles in pre-term and full-term infants. Clinical Neurophysiology doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2019.09.008 (October 15).

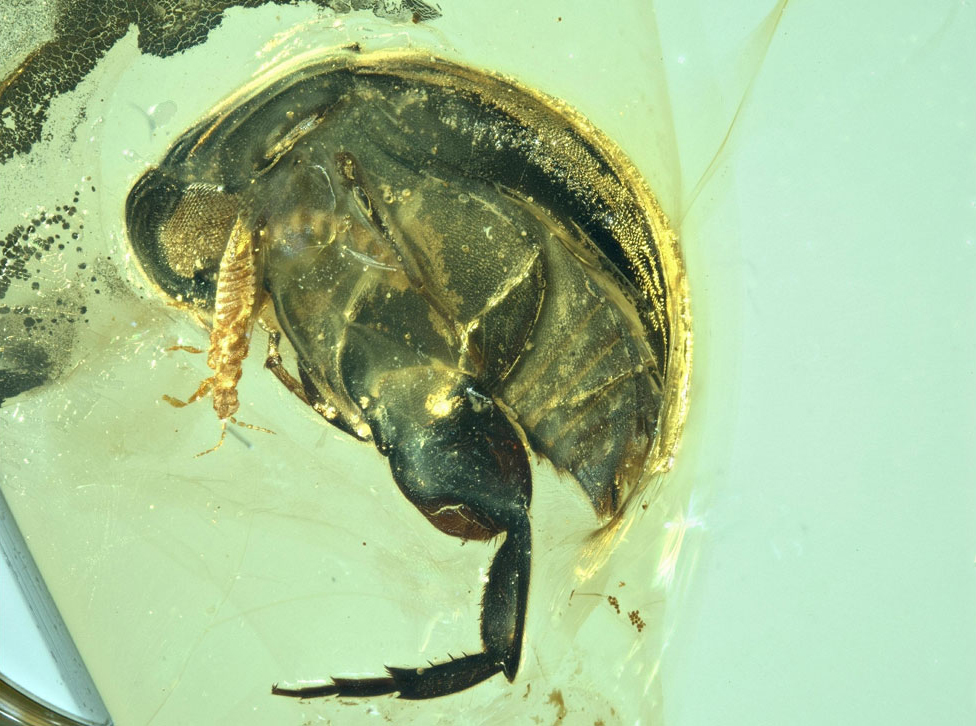

Prehistoric Insect Pollination

Amber miners in Myanmar have unearthed an unexpected treasure: evidence that insects were pollinating flowering plants 99 million years ago—50 million years earlier than previously known. During the Cretaceous Period, a beetle got stuck in tree sap with pollen clinging to its legs. The fossilized sap preserved both the beetle and the pollen in amber. Angimordella burmitina is part of the Mordellidae beetle family, also known as tumbling flower beetles. Like other members of that family, A. burmitina has a body shape designed for visiting flowers, and its mouth includes parts specialized for eating pollen. Paleontologists have known that both insects and flowering plants were common during the mid-Cretaceous Period, but this find is the first direct evidence that the prehistoric insects played a role in pollination. The fossil provides an early sign of coevolution between plants and insect pollinators.

Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology

Bao, T., B. Wang, J. Li, and D. Dilcher. Pollination of Cretaceous flowers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916186116 (October 11).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.