This Article From Issue

March-April 2018

Volume 106, Number 2

Page 75

In this roundup, digital features editor Katie L. Burke summarizes notable recent developments in scientific research, selected from reports compiled in the free electronic newsletter Sigma Xi SmartBrief. Online: https://www.smartbrief.com/sigmaxi/index.jsp

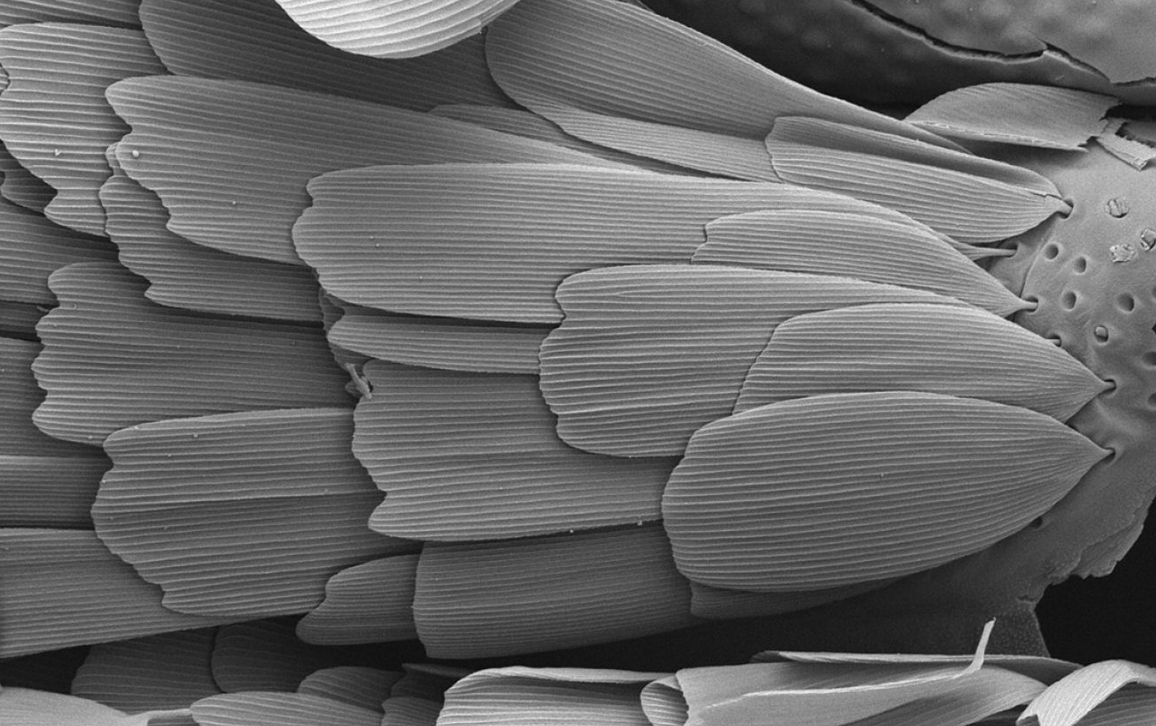

Earliest Ancestor of Butterflies

Butterflies and moths emerged at least 10 million years earlier than previously thought, according to wing scales Dutch researchers found while looking for ancient pollen grains. The team found about 70 wing scales in sediment from northern Germany that sat in a lagoon 200 million years ago, at around the time of the mass extinction that separates the Triassic and Jurassic periods. About 20 scales were hollow, a trait unique to modern moths and butterflies with long tongues that suck up flower nectar. Researchers previously thought that the long tongues evolved alongside flowers about 160 million years ago. The ancient insects may have used long proboscises to suck up sweet drops from nonflowering plants in a group that includes conifers.

Hossein Rajaei/Museum für Naturkunde

Van Eldijk, T. J. B., et al. A Triassic-Jurassic window into the evolution of Lepidoptera. Science Advances 4(1):e1701568 (January 10)

New Cellular Communication

Viral DNA sequences, incorporated long ago into the genomes of animals, may play a role in long-term memory formation. Two studies, one on mice and another on flies, focused on structures called extracellular vesicles, which form as the cell membrane pinches off from the cell. These vesicles circulate in the body, but their purpose is largely unknown. The studies showed that many vesicles contained a gene called Arc that is implicated in long-term memory formation. They also revealed that the Arc gene’s sequence is similar to that of a viral gene that transmits retroviruses’ genomes to new cells in protective bubbles called capsids. It turns out that the Arc protein also forms a capsid and carries the genetic code for itself, all encased in an extracellular vesicle. The study on flies showed that motor neurons (nerve cells that signal muscle contraction) form vesicles with Arc inside, which traveled to muscle cells. What the muscle cells do with them is not known, but flies lacking the Arc gene formed fewer connections between motor neurons and muscle cells. The study in mice showed that neurons that received vesicles produced the Arc protein when they were stimulated to fire. These observations indicate that vesicles containing Arc have a role in forming connections in the nervous system.

Ashley, J., et al. Retrovirus-like gag protein Arc1 binds RNA and traffics across synaptic boutons. Cell 172(1–2):262–274 (January 11)

Pastuzyn, E. D., et al. The neuronal gene Arc encodes a repurposed retrotransposon gag protein that mediates intercellular RNA transfer. Cell 172(1–2):275–288 (January 11)

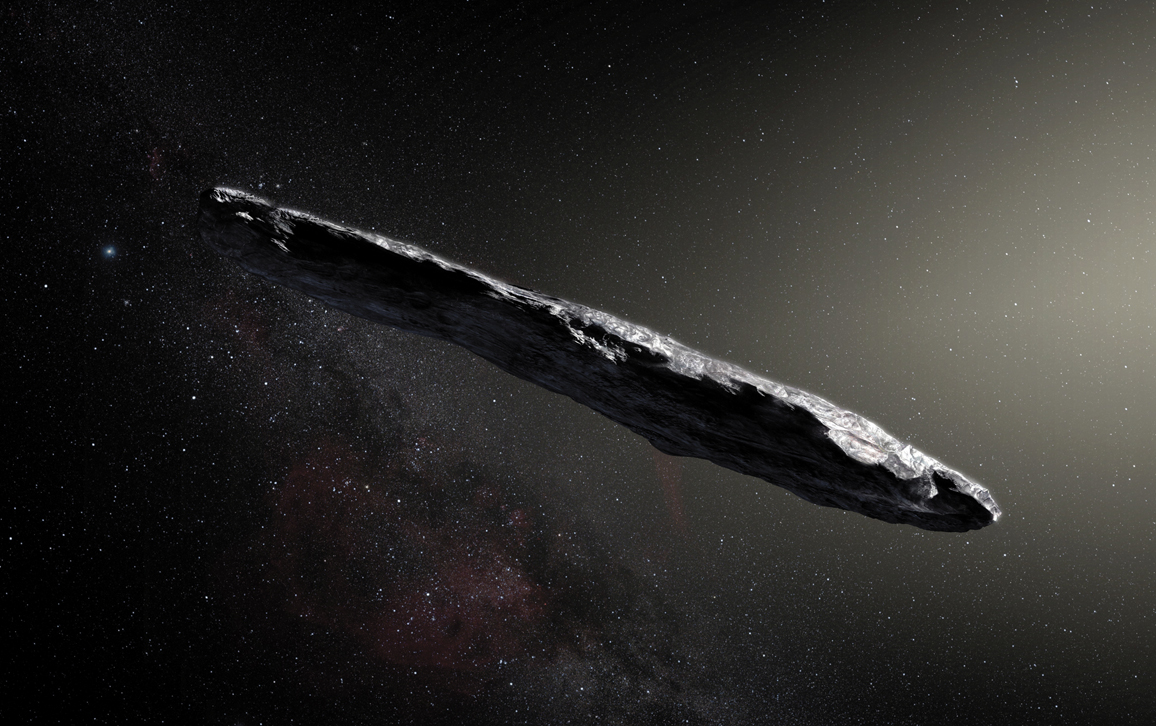

First Interstellar Object

ESO/M. Kornmesser

Initial studies are yielding insights into the nature of the first interstellar object observed by astronomers, an asteroid named ‘Oumuamua, which appeared on October 19, 2017, in images from the Pan-STARRS 1 telescope. It’s long been thought that if other planetary systems formed as ours did, then such a process would produce vast numbers of asteroids and comets that sometimes pass through our Solar System. The new find allows astronomers to directly explore conditions in another planetary system. ‘Oumuamua is elongated—more so than any asteroid observed in our Solar System—and is at least 300 meters long. The strange shape led to speculation that it is the product of a collision between other objects. As ‘Oumuamua approached the Sun, its lack of outgassing suggested it held no water or ice. Further modeling, however, indicated that a carbon-rich outer layer could have shielded any subsurface ice when it approached the Sun. ‘Oumuamua’s similarities to objects in our Solar System, such as its grayish-red surface, suggest commonalities between the way the planets formed here and elsewhere. Statistically, visitors such as ‘Oumuamua should be common—and now astronomers are better prepared for the next one.

Fitzsimmons, A., et al. Spectroscopy and thermal modelling of the first interstellar object 1I/2017 U1 ‘Oumuamua. Nature Astronomy 2:133–137 (December 18)

Earliest Humans in Americas

The second-oldest genome sequenced from a New World human revealed a lineage of early arrivals to North America, yielding clues about how humans arrived there. The DNA comes from the bones of a baby who died 11,500 years ago in central Alaska. The baby, named Xach’itee’aanenh T’eede Gaay, or Sunrise Child-Girl in the local Athabascan language, was more closely related to Native Americans than to any other humans with DNA available for analysis. But she was part of a new lineage, the Beringeans, that split off from the ancestors of Native Americans about 20,000 years ago. Her place on the human family tree indicates that the ancestors of all Native Americans diverged from Asian ancestors 36,000–25,000 years ago. So Native Americans’ ancestors became genetically isolated in East Asia before they migrated to North America. When Xach’itee’aanenh T’eede Gaay was alive, at least two genetically distinct populations were in North America. Whether the Beringeans’ divergence happened in Asia or North America is unclear.

UAF photo courtesy of Ben Potter.

Moreno-Mayar, J. V., et al. Terminal Pleistocene Alaskan genome reveals first founding population of Native Americans. Nature 553:203–207 (January 3)

SARS Virus Reservoir Is Bats

Severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, emerged in China in 2002; the exact origin of the outbreak has been a mystery until now. It was known that masked palm civets sold in an Asian market had passed the disease to humans, but it was unclear whether the civets were the source of the disease or the recipient from another animal. Mounting evidence implicated bats as the source, but all related viruses isolated from Asian bat populations in the region were genetically distinct from the strain that caused the outbreak. After sampling bats in a cave in southern China, Chinese researchers have discovered 11 new SARS related viral strains from horseshoe bats, indicating they are the likely reservoir.

Hu, B., et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathogens 13:e1006698 (November 30)

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.