This Article From Issue

November-December 2006

Volume 94, Number 6

Page 559

DOI: 10.1511/2006.62.559

The First Human: The Race to Discover Our Earliest Ancestors. Ann Gibbons. xxvi + 306 pp. Doubleday, 2006. $26.

Ever since a 1924 revelation first pointed to Africa as the cradle of humankind, a slow but steady stream of fossil discoveries has brought a general view of human evolution into focus. The pace has accelerated in the past 15 years, rapidly yielding an intriguing yet bewildering array of fossils of early ancestors of Homo sapiens. These new finds push back the base of our unique line, and that of our not-so-distant cousins, to possibly 6 or more million years ago. This time period is tantalizingly close to what most genetic models predict for the divergence of lineages that ultimately evolved into humans and chimpanzees. Finding a representative of the species that took the first step—on two legs—toward becoming human is indeed one of the key pursuits of paleoanthropology.

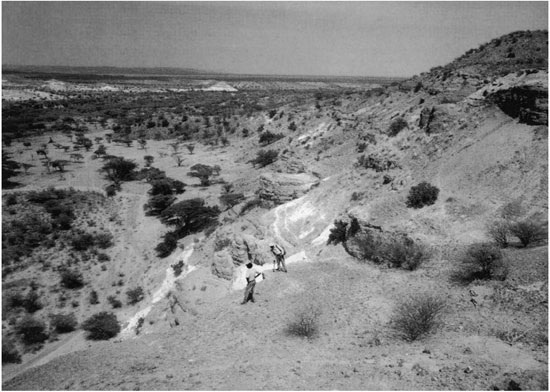

From The First Human.

Much of the action has taken place in East Africa, along with a surprising and scientifically challenging set of discoveries in Chad. These recent finds of our earliest ancestral remains comprise the focus of Ann Gibbons's The First Human. Despite this choice of title, the fossils discussed represent species that are far from what one would ordinarily call "human," as the author acknowledges. Indeed, she quotes Berkeley paleoanthropologist Tim White's wry comment about a species that many regard as one of our distant ancestors, fossils of which his team discovered in Ethiopia: "You wouldn't invite Ardipithecus ramidus to dinner." The boundaries of the definition of "human," let alone recognition of the "first human," are a subjective matter. Gibbons is able to distinguish clearly between subjectivity and scientific rigor, and therein lies a good part of her tale.

Gibbons is a talented science writerwho has reliably synthesized the morass of discoveries and details for news pieces in Science magazine, elucidating the extension of our past into uncharted territory. She is uniquely positioned to write this book and is exceptionally wellinformed—which is what makes the final product somewhat disappointing. Her intimacy with the subject matter and firsthand experience with the players do not consistently translate into a gripping story. In her patchwork chronicle of historical and recent events, Gibbons doesn't catch her stride until near the end of the third chapter, after which the pace occasionally falters, being bogged down with too much irrelevant detail. She lacks the flair for folding in the dramatic with emerging scientific insights that is found among science writers such as Pat Shipman (for example, in The Man Who Found the Missing Link, published in 2001). One also longs for the historical sense of such academic authors as Tom Gundling (First in Line, 2005).

Nevertheless, the stories are interesting in and of themselves, and Gibbons is one of the few to have access to a large number of tidbits that otherwise would be lost to posterity. One must be a careful reader, however. The book is lightly peppered with minor and nuanced, but irritating, inaccuracies. For example, in her recounting of Raymond Dart's 1924 discovery of the Taung child—the type specimen of Australopithecus africanus and the first fossil evidence of human origins in Africa—she states that Dart "never went to see where in a South African limeworks the Taung baby skull was found." It is true that the Taung skull was shipped to Dart and that he didn't goto Taung—until 1947, when he joined the University of California, Berkeley, expedition to the site. That belated visit could have been parlayed into a more accurate and thought-provoking story.

The jacket cover of The First Human promises "intense rivalries" in the "highly competitive world of fossil hunting." Although I can't blame Gibbons, who may not have had any influence on what was said here, this description brings on my heaviest sigh. At a time when evolutionary theory is under siege by antiscience proponents, such as the supporters of intelligent design, we don't need to provide them with ammunition by highlighting a handful of quirky squabbles on the sidelines of an otherwise respectable science.

All disciplines have their characters and contentions, butit is true that there have been some particularly emotional disputes in paleoanthropology. To be sure, there is the ever-present competition for grants and recognition. But beyond that, there is certainly something deeply personal about picking out one's great-grandparents from scant and vague snapshots of the distant past. And after the endurance tests we "fossil hunters" go through to find those glimpses of the past, it's indeed nice to have the satisfaction of knowing that one's discovery reveals an ancient forebear. Moreover, at times some scholars in our field have tended to descend into uncanny bitterness and downright skullduggery. Gibbons pulls no punches in documenting some of the more notorious episodes, such as paleontologist Martin Pickford's self-publication of Richard E. Leakey : Master of Deceit, a book full of allegations against Leakey, who inherited the mantle of Kenyan paleoanthropology from his famous parents, Louis and Mary.

Fortunately, the majority of Ann Gibbons's book is about much more than what is advertised in the provocativecover blurb. Contentiousness may sell books, but the subtext of what Gibbons writes demonstrates a much more inspiring moral: Cooperation among scientists is what really leads to further insights. That is why, after all my nitpicking, on the whole I give this book a positive nod. Paleoanthropology might be considered by some to be a "competitive" sport, but nothing comes through stronger than the message that it is a team sport in which the "winners" provide lessons for us all. Coming in second in the so-called "race" for the earliest human ancestor elicits as much information as coming in first—or, I should say, first for now.

One example is the contribution of Michel Brunet, a highly respected French paleontologist but an outsider to paleoanthropology. His story is one of sandstorms and amazing discoveries in the Djurab desert of Chad. Although the pressures of such desert fieldwork resulted in a few elements of discord, recounted by Gibbons, Brunet's hard-earned discovery—made by his team, I must add—and analysis of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, quite possibly the earliest known skull of any ancestral human species, is a tale to warm scientific hearts. Prior to publication, Brunet consulted with many of the best and brightest minds in paleoanthropology around the world before making any rash decisions about the importance of his team's find. Other such examples of cooperation in both deserts and labs abound in Gibbons's book. And that is how science moves forward.

In the final section of The First Human, titled "The Wisdom of the Bones," Gibbons comes into her true element as a science writer. Despite starting with a riveting depiction of a rather prickly academic conference in France (drama welltold this time), Gibbons does whatshe does best: She adroitly summarizes complex science in clear and simple terms that are the envy of those of us who write college textbooks. She also ends by giving a wink and a nudge to the future of paleoanthropology, but I won't steal her closing lines. You'll have to read them yourself.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.